TRUTH and POLITICS by Hannah Arendt

Here is a summary of “Truth and Politics” written by Hannah Arendt and published in 1967 by The New Yorker magazine. If you are interested in Hannah Arendt’s work, I have also written an article synthesising her essay “Lying in Politics – Reflections on the Pentagon Papers” (1972). Anyone interested in the notion of “post-truth” should read these two essential essays.

Key takeaways:

- Liars dismiss truth as mere opinion, and, when accused of lying, they portray their lies as opinions. Since everything is regarded as opinion, everything – including well-established factual truths – can be debated.

- Consequently, people lose their bearings in the world. They start doubting everything. Thus, they look for certainty, which they find in speakers who manage to reassure and praise them.

- The most convincing speakers rise to power, regardless of whether they tell the truth or lie. Liars, in the person of demagogues and sophists, happen to be the most convincing speakers.

- Liars must be able to lie to themselves in order to annihilate the truth they want to hide from others; otherwise, the truth finds refuge in them.

- History rewriting and revisionism undermine the stability, brought by historical factual truths, upon which society learns and grows. Without stable historical foundations, political progress is impossible: history is bound to repeat itself.

Throughout her essay, Hannah Arendt focuses on factual truths, that is to say truths that concern events and that are established by witnesses and testimonies. Examples of factual truths would be “Germany invaded Belgium in August 1914” or “2 + 2 = 4”. Philosophical truths, such as “it’s better to suffer wrong than to do wrong” (Socrates), differ from factual truths, as they are subject to debate and can be regarded as opinions to a certain extent.

Factual truth as a political counter-power

She asserts that factual truth is in itself a political counter-power. Given that truth is beyond agreement, dispute, opinion, or consent, it then possesses a coercive force. Truth imposes itself on everyone. Therefore, autocratic rulers feel threatened because they cannot monopolise its coercive force. As a matter of fact, unlike unwelcome opinions that can be contested and debated, unwelcome facts possess an “infuriating stubbornness that nothing can move except plain lies“. The relationship between lying and power is at the core of Hannah Arendt’s essay and broader work on totalitarian regimes’ strategies to control their population and retain power.

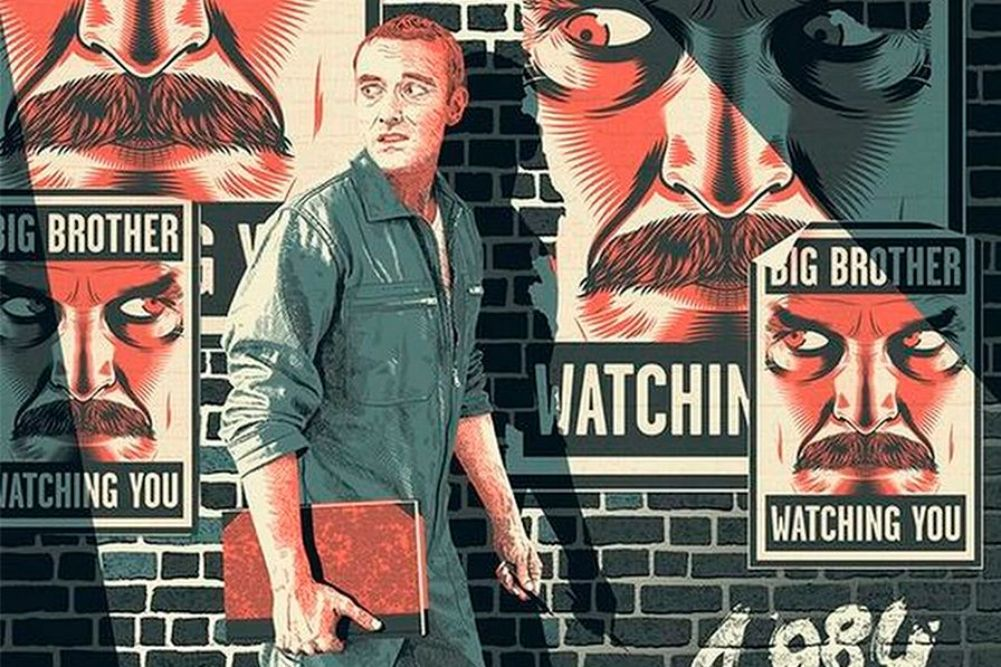

Information manipulation under totalitarianism

Totalitarian regimes resorted to information manipulation, history rewriting, and image-making in a bid to distort reality according to their ideology and, first and foremost, to the political interests of their ruling elite. For instance, it is a factual truth that Trotsky played a major role in the 1917 Russian Revolution, yet he doesn’t appear in Soviet Russian history books. It is worth noting that, when a fact of importance is forgotten or lied away, chances are very slim that it will one day be rediscovered. Nowadays, we can still find instances of history rewriting and revisionism in many countries, such as Vladimir Putin’s Russia, Xi Jinping’s China, or Donald Trump’s USA.

Blurred lines between truth, lies, and opinion

Despite their coercive force, factual truths remain vulnerable to plain lies. Indeed, Hannah Arendt argues that, in order to dismiss unwelcome factual truths, liars portray them as mere opinions. To do so, they simply have to point out that factual truths rely on testimonies and records that can be suspected as forgeries. Thus, liars blur the dividing line between truth and opinion. However, they also blur the line between lie and opinion. In fact, when they struggle to make their falsehood stick, liars simply pretend that it is their opinion, i.e. the expression of their freedom of opinion (constitutional right). Nevertheless, Hannah Arendt asserts that for one’s freedom of opinion not to be a farce, factual information should be guaranteed, and facts themselves should not be in dispute.

Loss of bearings

By presenting both truths and lies as opinions, liars destroy our ability to distinguish truth and falsehood. In other words, they destroy a mental means by which we take our bearings in the real world. In fact, they contribute to spreading doubt as to what can be trusted or not. As a consequence, well-established factual truths and figures of authorities, upon which we rely for our sense of direction and reality, start being discredited. According to Hannah Arendt, this loss of bearings constitutes a common experience under totalitarian rule.

No progress without historical foundations

This subversive enterprise also targets our past – more precisely our common understanding of the past. By questioning well-established historical facts and rewriting history, liars and propagandists give themselves boundless possibilities for lying since everything that once happened could just well have been otherwise. As a consequence, they deprive the political realm of its stabilising force, i.e. its ability to draw from past experiences to innovate and initiate progress. The only outcome is the emergence of sterile political projects bound to repeat the history.

The population’s inability to resist and revolt

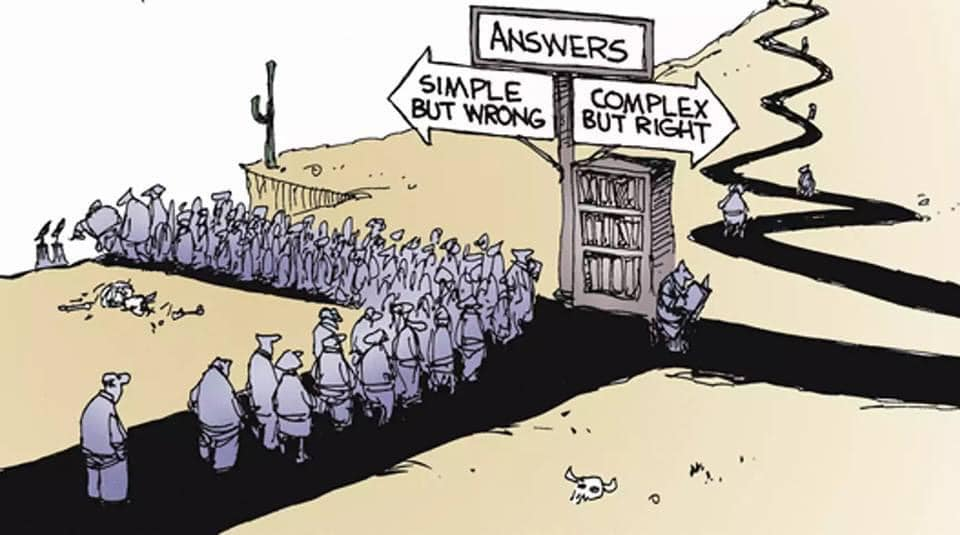

This phenomenon is reinforced by the apathy of the general population. The latter has indeed lost its mental and moral certitudes; it is no longer able to distinguish truth from falsehood as well as good from bad. Nothing anymore can be held for certain. Everything can be doubted. From this (manufactured) uncertainty arises fear, which causes people to look desperately for certainty. Deprived of critical thinking and of their bearings, people are unable to think and judge by themselves and, as a result, become easily manipulated. Figures and organisations that manage to gain their trust then turn into their guiding light, i.e. the only lens through which they will perceive reality.

The persuasiveness of liars

Unfortunately, the figures or entities that are the most convincing, and thus the most able to gain people’s trust, happen to be liars, not truth-tellers. In “Truth and Politics”, Hannah Arendt demonstrates that liars, unlike truth-tellers, have the power to mobilise crowds and inspire political action. She claims that merely telling factual truths does not lead to action; it rather leads to inaction since people tend to accept things as they are. Thus, truthfulness is not to be found amongst political virtues, as it does not help politicians who strive to change the world. As for liars, they are free to shape their discourses and opinions to fit the expectations of their audience. On the contrary, truth-tellers do not enjoy the same argumentative freedom and have to deal with reality’s disconcerting contingency, that is to say information that contradicts one’s mental framework. Indeed, reality frequently “offends the soundness of common sense”, as Hannah Arendt wrote in her other essay “Lying in Politics” (1972).

Self-deception to annihilate the truth

Nonetheless, to effectively lie to others, one must be able to lie oneself. As a matter of fact, the persuasiveness of liars rests upon the semblance of truthfulness they are able to create. They must remove any hesitation or doubt that may arise from their argumentation. Self-deception is the most efficient means to this end. However, self-deception is not a conscious effort made by liars to improve its persuasiveness; it is actually a natural process. In fact, sticking to anything, truth or lie, that is unshared with fellow men requires a considerable strength of character. Hence, self-deception comes naturally when liars do not make particular efforts to remember the truth. Moreover, cold-blooded lying is counterproductive. Indeed, the cold-blooded liar remains aware of the distinction between truth and falsehood, so the truth he is hiding from others has not yet been manoeuvred out of the world altogether; it has found its last refuge in him.

If you are interested in Hannah Arendt’s work, I have also written an article synthesising her essay “Lying in Politics – Reflections on the Pentagon Papers” (1972).

1 Comment

fapello · 18 September 2025 at 10:16 am

The article provides a profound insight into the manipulation of truth by totalitarian regimes. Hannah Arendts analysis on how lies blur the line between truth and opinion is particularly striking, highlighting the vulnerability of factual truths to political interests. The discussion on the loss of bearings and the populations inability to resist under such regimes is thought-provoking, emphasizing the dangerous consequences of disseminating falsehoods. The article serves as a stark reminder of the importance of critical thinking and the need to safeguard factual truths in a world where information can be easily manipulated.