CHINA – NORTH KOREA, an unswerving alliance?

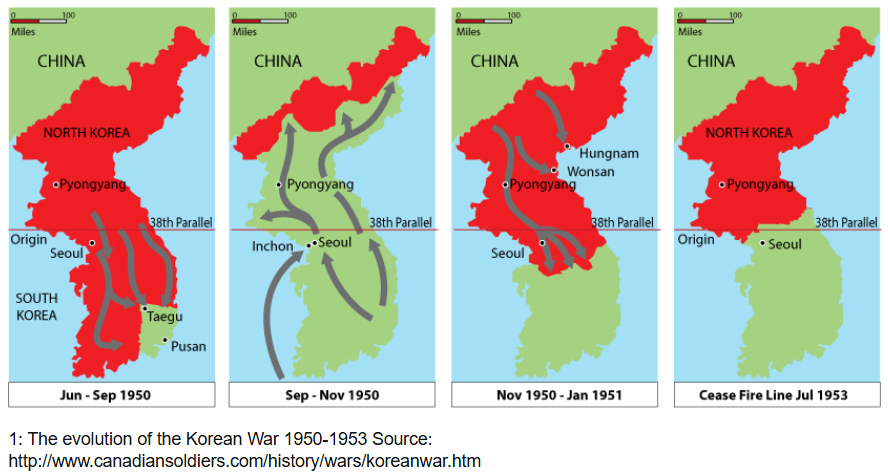

The Sino-North Korean alliance traces its origins to the 1950-1953 Korean war during which the two countries fought to contain Western influence – now entrenched just beyond the demilitarised zone (DMZ) along the 38th parallel. North-Korea’s international isolation has made it heavily dependent on China, a situation that serves Beijing’s geostrategic interests. However, this alliance has grown increasingly unstable in recent years.

I) The economic and diplomatic alliance between China and North Korea (A) rooted in historical ties and ideological affinity (B)

A. Economic and diplomatic relations

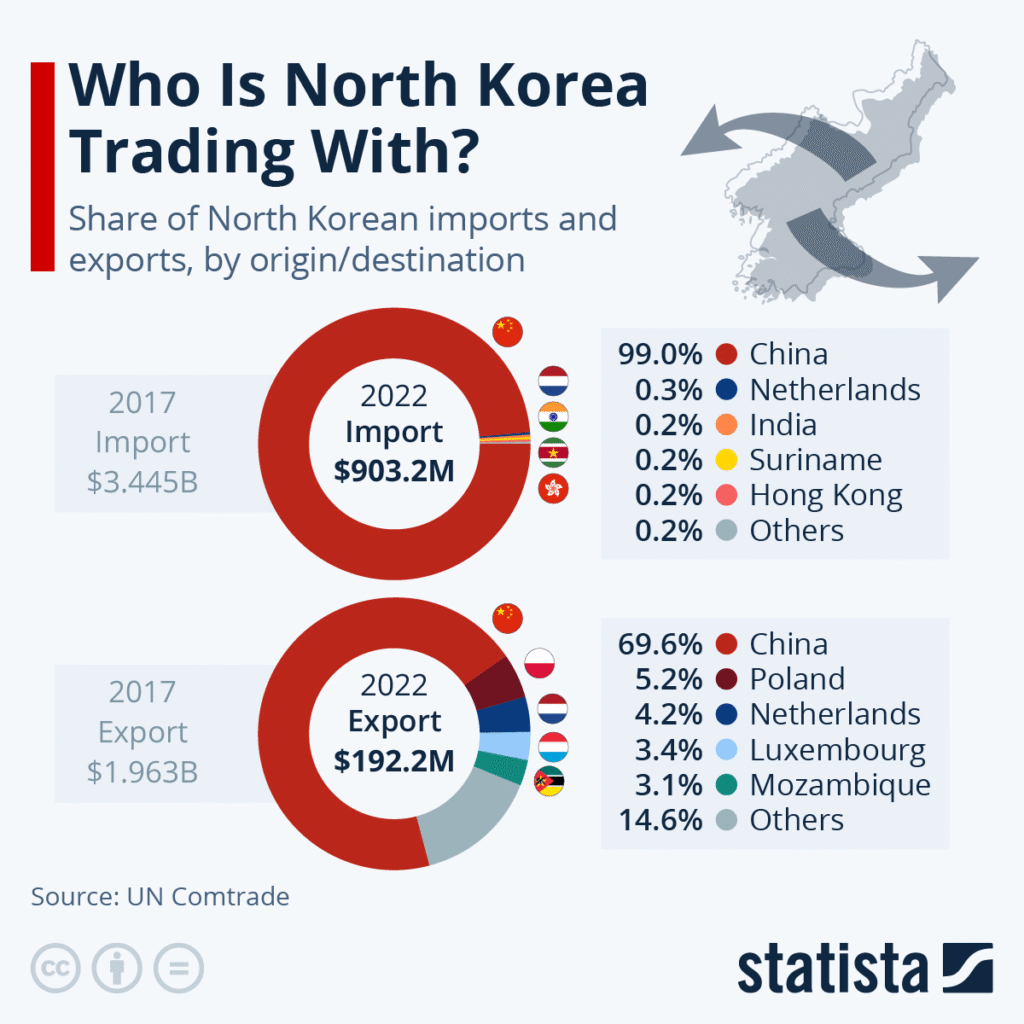

The asymmetrical nature of the relationship between China and North-Korea is reflected in the latter’s trade figures: China accounts for 99% of North Korea’s imports and 70% of its exports. China also invests in the country’s mining sector to extract critical resources such as magnesite, zinc, tungsten, or iron.

In order to maintain its foreign currency reserves, North Korea dispatches agents from Office 39 to work abroad as bartenders, waiters, or construction workers – primarily in China which stands as the main destination for North-Korean labourers.

In fact, following the introduction of international sanctions in 2005-2006 in response to North Korea’s military nuclear programme, the country has become increasingly isolated on the global stage. Hence, its economic and diplomatic survival hinges on China’s support, particularly within the UN Security Council.

B. Historical and ideological proximity

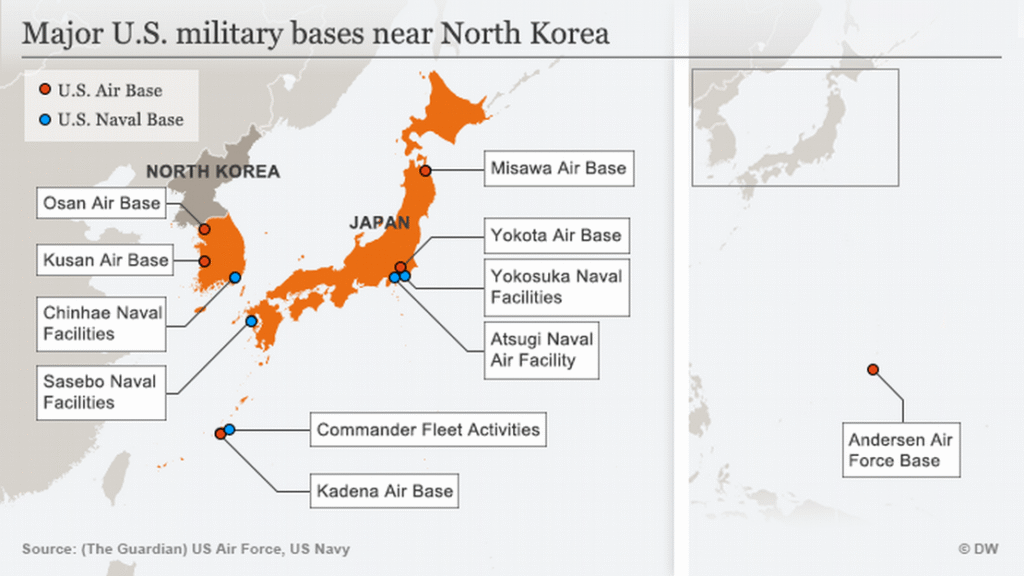

The Sino-Korean alliance emerged following the pre-emptive war launched by China in 1950 to repel pro-Western troops from the Korean peninsula. Since then, North-Korea has served as a strategic buffer zone between China and the West, embodied by US military bases in South Korea (around 25,000 troops) and Japan (around 55,000 troops). North-Korea also serves as a proxy for Chinese disruption operations against the West. Indeed, China has reportedly cooperated with the North-Korean cyber unit named Lazarus Group in conducting cyber attacks worldwide.

II) However, the Sino-Korean partnership comes across as unstable (A) and North-Korea intends to gain diplomatic autonomy (B)

A. A faltering alliance

Behind the diplomatic veneer, the frequent and arbitrary termination of exploitation contracts granted to Chinese companies by North-Korean authorities epitomises the instability of the bilateral relationship. The pervasive trade and legal uncertainty surrounding around North-Korea’s business environment hampers deeper integration with China’s economy.

Moreover, in 2018, in an effort to improve its public image, China began applying UN Security Council international sanctions introduced in 2005-2006 against North-Korea. Beijing has also openly called for the denuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula, as it did during the tripartite meeting of the Chinese, Japanese and South-Korean ministers of Foreign affairs in March 2025.

B. Greater North-Korean geopolitical autonomy

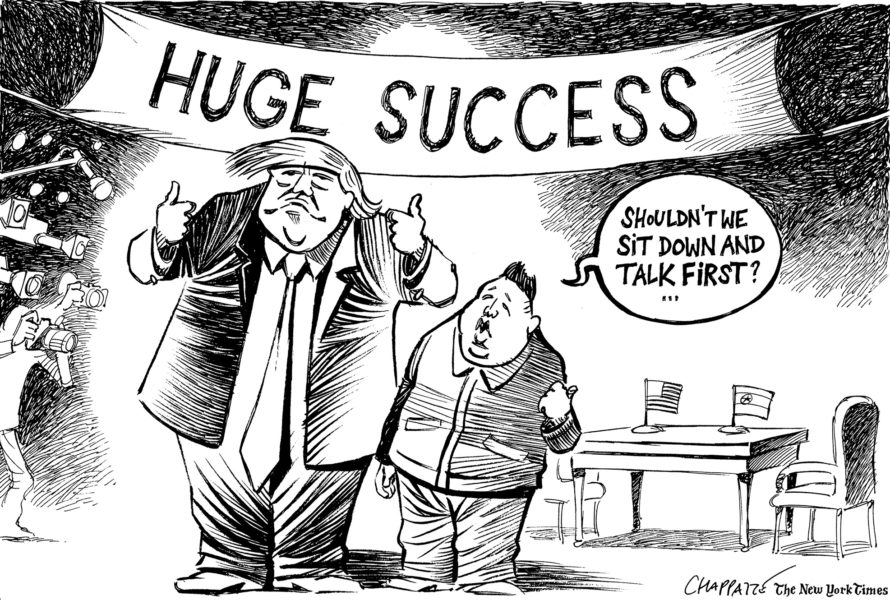

Kim Jong Un’s North-Korea has endeavoured to pursue a more autonomous, independent foreign policy vis-à-vis China. For instance, Pyongyang neither consulted nor informed China before signing a mutual defence partnership agreement with Russia in June 2025 – a development that could heighten regional instability, as Russia’s involvement may draw greater Western attention to the peninsula. North-Korea is therefore acting in a manner that contradicts the role that China has long assigned to it: that of a buffer zone against the West. Similarly, North-Korea barely consulted China in 2018 when Kim Jong Un met with President Trump at the 38th parallel. Consultations are equally seldom when it comes to missile tests launched over Japan .

0 Comments