MALI and France’s counter-terrorism operations

What you want to understand… 🤔

- What is the chronology of the French intervention in Mali and the Sahel region?

- Can we speak of neocolonialism? What were France’s motivations to intervene?

- Was France alone to intervene in the region?

- Should the French withdrawal be associated with a defeat?

- What role do the Russians play in this part of the world?

I. Background information on Mali

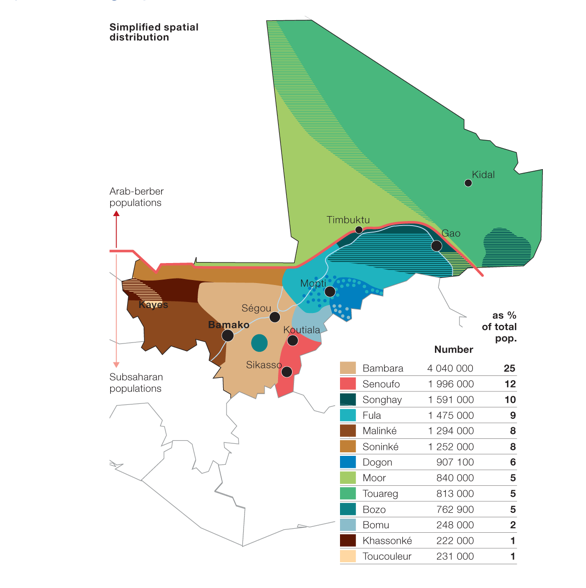

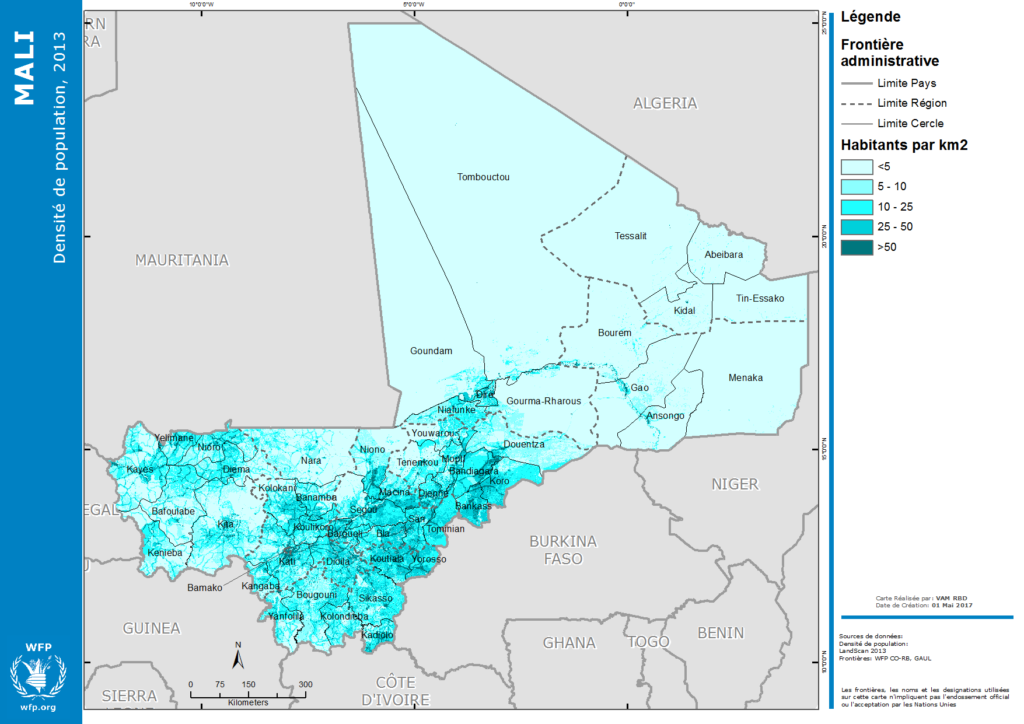

Mali is not a nation-state like most African countries that have been colonised. There is a great ethnic diversity in Mali with a clear division North/South. In Northern Mali, we find a majority of Arabs and Berbers (mainly Tuaregs and Moors) whereas black sub-Saharan populations live in the South. Besides, people living in the North only represents 7% of the whole Malian population.

The current situation takes its roots in the 2012 Tuareg rebellion that demanded the creation of an independent region in the North of Mali, the Azawad.

The media have explained this rebellion with an argument revolving around North/South differences of socio-economic development and insisting on the Malian ethno-racial divide. However, even though it may explain in part what happened in Mali in 2012, this is far from being satisfying and actually just comforts us in our pre-conceived mental patterns that racial differences are at the roots of most conflicts.

We will now quickly review this explanation used by the media before understanding what actually caused the 2012 Tuareg rebellion.

A. The North/South divide

When Mali was under colonial rule, until 1960, France mainly developed infrastructures in the South as it was more humid which allowed agriculture. As a result, Malian intellectual and cultural elites progressively gathered in the South of Mali around Bamako.

The North/South division is accentuated by Southern black populations’ negative perception of Tuaregs who live in the North. As a matter of fact, the latter used to participate in the rasias to find new slaves for the European colonial expansion in Africa.

The socio-economic differences that ensue from History are one of the reasons why there are tensions between the North and the South of Mali. However, this is not the main factor accounting for the 2012 Tuareg rebellion.

B. An inter-Tuareg power struggle is the root of the 2012 crisis

As a matter of fact, Amadou Toumani Touré the Malian President between 2002 and 2012, had a certain propensity to resort to the divide and rule strategy when it came to establishing his authority in Northern Mali. Indeed, his strategy to prevent armed insurgency in the North was to outsource state functions to “Tuareg clans of lower status, opportunistic local elites, and manageable Arab armed factions and militias” according to Anouar Boukhars (2013).

This approach consequently upset nobles and upper-class Tuaregs (Ifoghas and Idnanes) who wanted to regain their authority that was given to Tuaregs of lower social ranks (Imghads). That’s why they created in 2011 the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) in order to secede from Mali and re-establish their authority. Of course, Tuaregs of lower social ranks who were favoured by Bamako protested against this conservative rebellion and formed in 2014 the Imghad Tuareg Self-Defense Group and Allies (GATIA).

Therefore, the principal cause of this conflict is an inter-Tuareg power struggle. It is not just a mere problem of centre vs. periphery, it is a problem of resources and allocation of political responsibilities in Northern communities.

II. Chronology of the French intervention in Mali and the Sahel region

A. An imminent threat to the Malian government (2012-2013)

1. The Tuareg rebellion (January-April 2012)

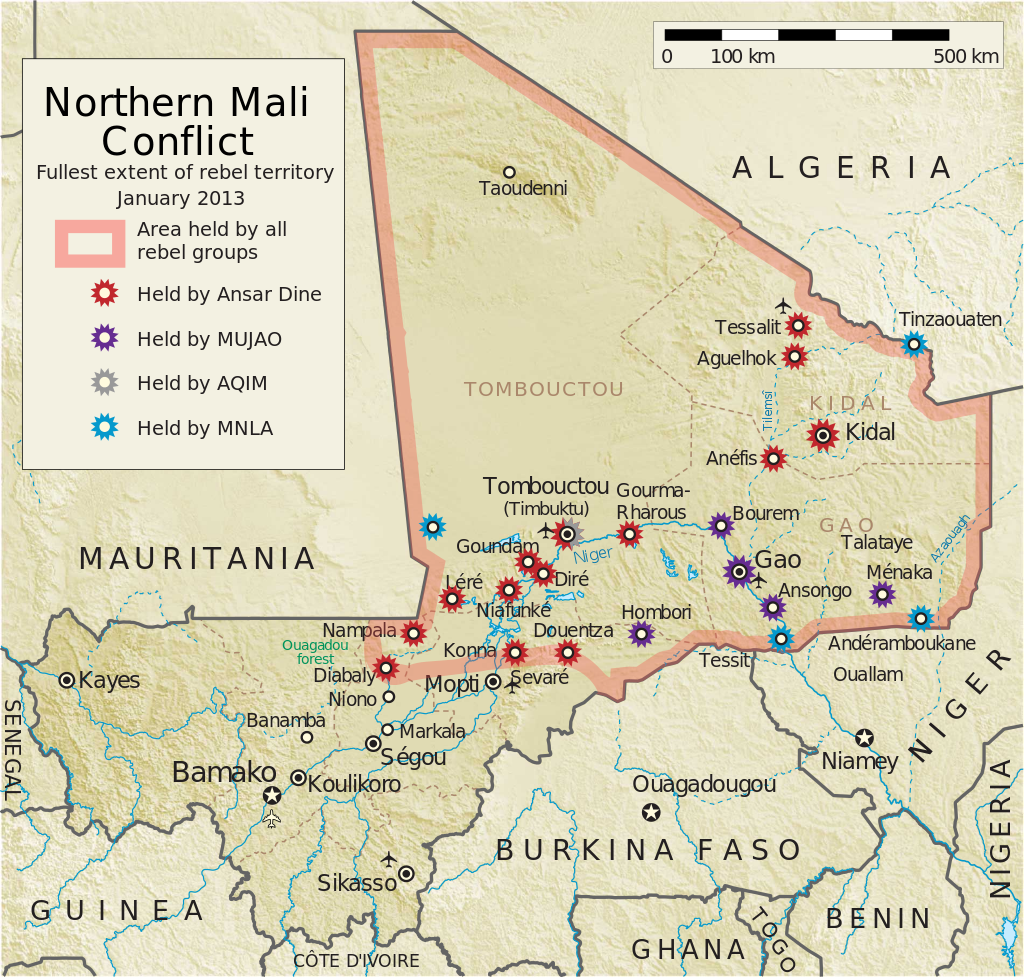

In 2012, Tuareg rebels from the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) stood up against the Malian government to create an independent region in the North of Mali, the Azawad.

It was not the first time that Tuaregs demanded a greater autonomy for the Azawad. In fact, they already rebelled in 1963, 1990 and 2006.

They got help from Islamist groups like:

- Ansar Dine: Malian group created in 2012, with a majority of Tuareg fighters and under the leadership of Iyad Ag Ghaly.

- AQIM: al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. They mainly fled Algeria where the government chased them following the Algerian Black Decade 1990s.

- MOJWA: Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa. It is a Malian group that was created in 2011 by a dissident from AQIM named al Sahrawi.

In March 2012, Malian soldiers unsatisfied with Touré’s government handling of the crisis decided to organise a coup. However, the ensuing political instability actually helped the MNLA pursue its goal. Consequently, the Tuaregs controlled the entire North of Mali in April 2012.

Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that other ethnic groups like Arabs and Moors in the North-West of Mali were quite reluctant to the idea of seceding from Mali. In fact, they were satisfied with the status quo that allowed economic development and peace.

2. The Islamist threat

Once the MNLA controlled Northern Mali, tensions rose with their Islamist allies as well as with local populations. They disagreed on how the Azawad should be ruled. Islamist groups wanted the independent region to rest on a strict interpretation of the shari’ah (Allah’s law).

As a result, within few months the MNLA lost most of its territories to the Islamists. The latter then headed towards the Malian capital Bamako. In December 2012, as they were progressing rapidly and capturing strategic places, the interim President Dioncounda Traore expressly asked France, through the United Nations, to intervene so as to prevent Islamist groups from seizing power in Mali.

We should mention that in this succession of events there were many more smaller Malian groups and militia whose allegiances were mercurial. Therefore, the Malian government, and later French forces, had great difficulties identifying clearly their enemies. Moreover, these groups enjoyed grassroots support, knew the ground on which they were fighting and were independent from each other meaning that when one was weakened it had no impact on the others. Besides, some of these groups are composed of almost 40% of former Libyan soldiers who, in 2011, brought with them experience and weapons from Muhammad Qaddafi’s fallen regime.

B. Operation Serval (2013-2014)

From January 2013 to July 2014, following President Dioncounda Traore’s request, French forces operated in Mali within the framework of Operation Serval. Their goal was to take back and secure the cities controlled by jihadists.

Within few weeks French forces seized Northern Malian cities and severely weakened AQIM and Ansar Dine while MOJWA fled to Niger and quickly dissolved. Nevertheless, AQIM, Ansar Dine and other smaller movements remained quite active especially in mountainous, arid and rural areas.

Besides, Tuareg separatists kept on fighting jihadist groups and sometimes allegedly also attacked Malian forces.

In the meantime, presidential elections took place and Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta was elected.

C. Operation Barkhane (2014-today)

1. French presence in the Sahel

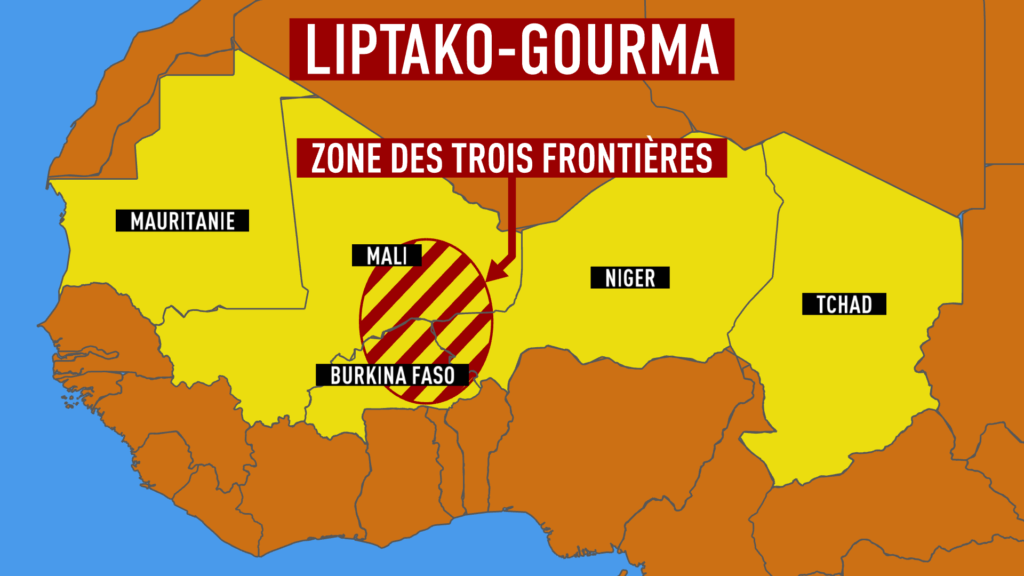

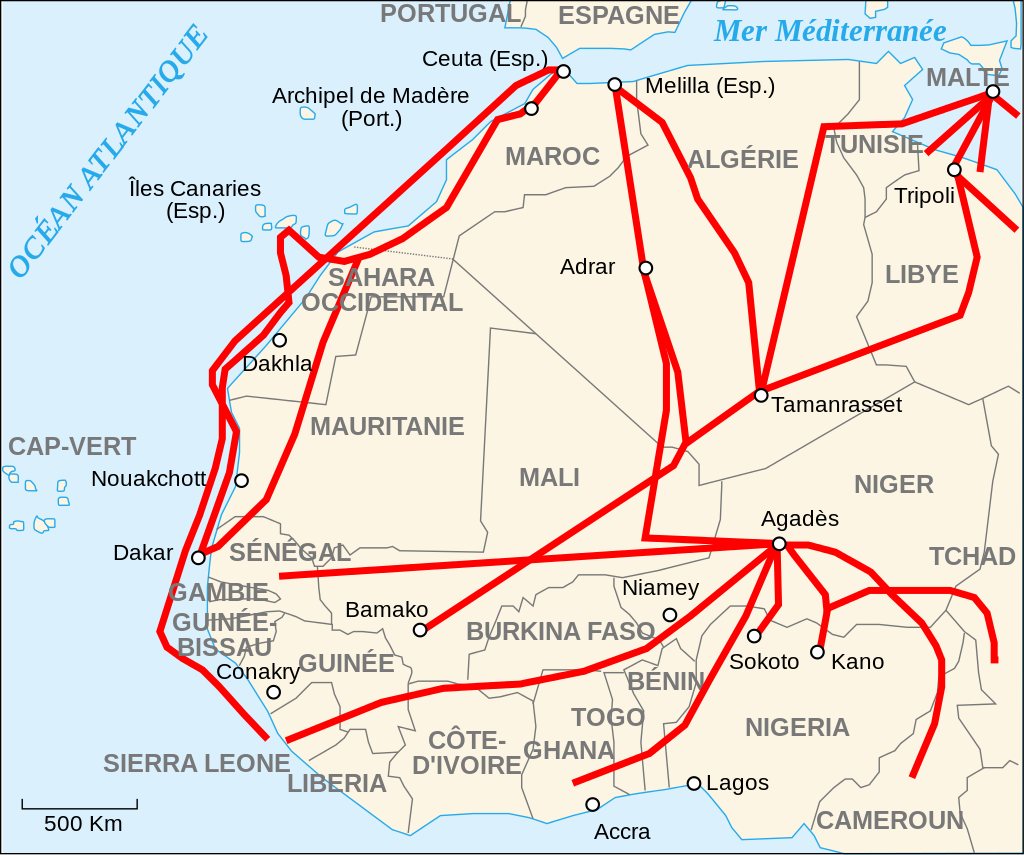

As of August 1, 2014, France deployed its troops in 5 countries of the Sahel region: Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad. Operation Barkhane thus succeeded Operation Serval. The objective was to help G5 countries fight jihadist groups in the region and thus prevent the creation of a haven for terrorists willing to attack Europe and France.

At the beginning of the intervention, France sent 3,000 troops. This number progressively increased to reach 5,100 troops in 2020. Operation Barkhane also counted hundreds of armoured vehicles, hundreds of logistic vehicles, around 20 helicopters, around 10 fighter planes, around 10 transport planes and 4 to 5 drones. These are just approximations in order for you to grasp the extent of the French presence in the Sahel region.

2. International presence in the Sahel

Several foreign missions were carried out in the region along with the French intervention.

For instance, since 2013, the EU has launched the European Union Training Mission in Mali (EUTM Mali). Thus it has sought to provide military training and strategic advice to Malian forces.

The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) is aiming at stabilising Mali by promoting a political solution to the conflict between Tuaregs and the Malian government. Between 10,000 and 15,000 peacekeepers belong to the MINUSMA.

We can also mention Task Force Takuba that was created in 2020. Its 800 troops are mainly special forces coming from several EU countries like Denmark, Italy, Sweden or Estonia. As part of Operation Barkhane, they operate under French command in the 3-frontier region and particularly in Mali.

Besides, it is worth noting that French operations relied not only but to a large extent on US intelligence.

3. Evolution of the conflict in the Sahel since 2015

Between 2015 and 2019, terrorist attacks in the region multiplied. In fact, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), created in May 2015, started carrying out terrorist operations in the region. As of 2017, under the pressure of French and foreign forces, Ansar Dine, AQMI and the Algerian group Al-Mourabitoune joined forces. They formed the Support Group for Islam and Muslims (Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin, JNIM).

Despite an intensification of jihadist attacks, French forces managed to eliminate the leaders of AQIM, of the JNIM and of the ISGS between June 2020 and August 2021.

4. An increasing political instability since 2018

In 2018, Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta came out victorious of the Malian presidential elections. However, despite the EU and international observers recognising the results, all the other candidates challenged them and accused President Keïta of a massive fraud.

Two years later, in August 2020, Malian army officers overthrew President Keïta while the streets demanded his resignation. The junta then appointed Bah N’Daw as the transition President and Moctar Ouane as Prime Minister.

Nevertheless, their turn to be overthrown came less than a year later, in May 2021. In fact, the junta was unsatisfied with the government’s composition and Colonel Assimi Goïta, leader of the previous putsh, took power.

D. Withdrawal of Western forces from Mali and arrival of the Wagner Group

1. Rising political tensions

In June 2021, President Macron announced the progressive withdrawal of Operation Barkhane’s troops. Only 2,500 to 3,000 would remain in the Sahel region.

This reduction of the French presence is due to rising tensions with the Malian junta. As a matter of fact, they didn’t share the same strategy and France criticised the lack of transparency with regards to how Malian authorities deal with jihadists.

In January 2022, tensions rose between the Malian junta and the authorities of Operation Barkhane. For example, Mali demanded Denmark to withdraw newly arrived troops engaged within the framework of Task Force Takuba because it didn’t expressly approve their deployment. Few days later, the French ambassador to Mali was expelled from the country. Moreover, the Economic Community of Western African States (ECOWAS) decided to both close their frontiers with Mali and impose an economic and financial embargo on the country.

France then decided that the conditions were not gathered anymore for Operation Barkhane to continue in Mali.

Besides, the French government emphasised that a thousand Wagner mercenaries were operating in collaboration with the Malian government. Wagner is a Russian paramilitary group that made itself known especially in Ukraine as it intervened unofficially at the behest of the Russian government.

2. Official and complete withdrawal of Operation Barkhane from Mali

That’s why, in February 2022, President Macron made official the departure of all Operation Barkhane’s troops from Mali for August 15, 2022. Nonetheless, these forces were then redeployed in the neighbouring countries in order to maintain the pressure on jihadist groups in the Sahel region. There are currently between 2,500 and 3,000 Operation Barkhane troops present in the rest of the Sahel region.

Only the Wagner group, the MINUSMA and a tiny part of the EUTM remain in Mali to this day.

3. Mali is isolating itself

We can also mention that Mali pulled out of the G5 Sahel force in May 2022. It means that Malian troops will no longer intervene military along with forces from Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad to fight jihadist groups in the Sahel.

Mali is currently isolating itself not only from its African partners but also from Western powers given that it relies now solely on Wagner mercenaries, even though it refuses to acknowledge their presence on its soil.

4. The Wagner Group

By withdrawing from Mali, France has left a power vacuum that benefits the Wagner Group that has won the Malian junta’s favour. Moreover, the Russian paramilitary group played an active role in fostering anti-French sentiment among Malians who ascribed their misfortune to their former colonizer.

With regards to recent developments in Mali, the Wagner Group has been unable to block terrorist jihadists who are now close to Bamako. The exactions they commit alongside Malian armed forces against civilian population actually benefit terrorist groups’ recruiting efforts.

Russian interests in Africa are still a bit unclear but they probably have to do with natural resources, industrial investments, ousting the West from the continent and gaining friends on the international stage.

III. The 2015 Algiers Peace Agreement

The “Accord pour la paix et la réconciliation au Mali” signed in 2015 in Algiers between the Malian government and various Tuareg movements like the MNLA.

The main provisions of the Algiers Agreement included:

- Territorial integrity of the Malian State

- More regional autonomy, in particular for the North

- Better representation of Northern populations in national institutions in Bamako

- Economic development

- Disarmament of rebel groups

This agreement is no longer relevant today, and actually was not even relevant at the time of the signature. For instance, disarmament was never implemented: there was even a rearmament of Northern rebel groups that fought each other (because inter-Tuareg tensions were not addressed by the Algiers Agreement) and that fought the growing jihadist influence. Besides, no political reform was carried out in Bamako to appease relations with Northern populations and foster national unity.

The weaknesses of the Algiers Agreement included:

- Jihadist terrorist groups didn’t participate in peace discussions because France refused to negotiate with them whereas they carried political claims and were a big part of the crisis in Mali.

- Too much focus on a North/South divide, which considers the North as a monolithic bloc whereas the Tuareg community is not united e.g. tensions between Ifoghas and Imghads.

- Central Malian communities were not given enough weight in negotiations. For example, Fula people represent a major recruitment pool for jihadist terrorist groups.

- Civil society was not associated: there were only armed groups that participated in discussions and thus only defended their own interests. Northern armed groups, contrary to what was thought, actually didn’t represent Northern populations as a whole.

IV. What were France’s motivations to intervene?

A. Why did Mali especially call on France to come to the rescue?

According to Maj. Gen. Olivier Tramond and Lt. Col. Philippe Seigneur (June 2013), France enjoys strong ties with the African continent, especially with its former colonies. We usually refer to this relationship with the term Françafrique. There are important French expatriate communities in Africa which implies that during political turmoil they are often the objectives of non-combatant evacuation operations (NEOs). Therefore, the presence of French troops in Africa is familiar to most countries suffering from political instability.

Moreover since 1985, France has a military agreement with Mali stating that French soldiers can be put at the disposition of the Malian government in order to organise and train Malian troops. Therefore, Malian authorities were used to the French military presence on their soil before the conflict broke out. That’s why they naturally reached out to France to help them in dealing with the crisis.

However, Malian authorities then felt the need to present the former colonial power’s intervention as inevitable and as the “least bad” option.

B. Securing access to natural resources

French economic interests in the region bore a substantial weight in France’s decision to intervene in Mali in 2013.

The North of Mali, that fell under Tuareg and jihadist control in 2012, is not really a strategic area in terms of natural resources. However, two Malian possible oil extraction sites are located around Gao and Kidal, as well as gold mines in Southern Mali. Nevertheless, no French company exploits these resources.

As a matter of fact, France has economic interests mainly in:

- North-West Niger where Areva exploits uranium deposits

- East Mauritania where TotalEnergies exploits oil reserves

As you can see on the map, these two regions are close to Malian borders. We can therefore make the hypothesis that France intervened in Northern Mali to prevent a potential expansion of instability in neighbouring regions where it has economic interests.

Furthermore, it is a good diplomatic manoeuvre for France to provide assistance to African countries in their fight against terrorist jihadism. In fact, France increases its chances to receive exploitation permits for the natural resources of its African partners.

C. Preventing the formation of a haven for anti-Western terrorists

France also sent troops in Mali in 2013 in order to prevent the formation of a haven for terrorists who may later launch attacks against Europe. It didn’t want the Sahel region to become an international platform for terrorism like Afghanistan under Taliban rule between 1996 and 2001.

Besides, having a regime upholding a strict application of the shari’ah in the middle of the Sahel would foster movements with similar ideologies in other African countries. The spread of an anti-Western rhetoric across Africa represents a direct menace for Europe due to these two regions’ geographic proximity.

That’s one of the reasons why France couldn’t let jihadist fighters seize power in Bamako in 2013.

D. A destabilisation of the Sahel would have major consequences for Europe

A destabilisation of the region would probably lead to a substantial migration wave to Europe. At first, refugees would flee jihadists’ authoritarian regime. Later, economic migrants would go to Europe seeking opportunities they can’t find in the Sahel. We witnessed similar situations in Libya and Syria after the 2011 Arab Springs and their ensuing civil wars.

Moreover, we can assume that illegal traffics would flourish in the Sahel after a take-over by jihadists. Traffickers would use the vast and non-monitored spaces of the Sahara to smuggle drugs to Europe through the Maghreb.

E. French citizens dwelling in Bamako

The presence of roughly 6,000 French citizens in Bamako in 2012/2013 might also have played a role in France’s decision to send troops in Mali. As a matter of fact, the Malian army was overwhelmed and unable to ensure the security of Malian inhabitants. Therefore, France felt that it had to step up and protect its citizens living there.

V. Remarks and analysis

A. The three main reasons for the failure of Barkhane

- Misunderstanding of Malian politics and different objectives i.e. France wanted to fight terrorism while Mali focused on regaining territorial control and sovereignty

- France was too assertive and ambitious about neutralising all terrorists in the Sahel

- Local populations did not understand how and why the French army could not defeat some terrorists who had much less firepower

B. The political limits of the French intervention in Mali

France achieved military victories on the ground against terrorist jihadist groups. However these operational successes didn’t carry much weight in the eyes of the population, which made it easier for Russia to step in with an anti-French narrative. France failed to communicate efficiently to local populations on its mandate and its military achievements.

Anyway, the solution to the crisis in the Sahel can only be political. In this respect, some remarks can be formulated.

Going to war but for what peace?

1. The lack of a comprehensive and efficient strategy for the economic and political development of Mali

One of the limits of French and foreign governments’ development strategy was the fact that they “gave little attention to problems of Malian leadership” and instead focused “their aid on social and economic development” according to Mark Moyar (2015). However, this aid is by nature temporary and there needs to be trustworthy local political leaders to ensure a sustainable socio-economic development for the country. Furthermore, there also needs to be a political program for the country and in particular for its youth. As a matter of fact, the Malian state currently lacks the capacity to meet youth expectations. This situation increases the risk of seeing the lifeblood of the country turn to non-state actors, including terrorist jihadist groups, for essential goods and hopes of improvement of their socio-economic status.

Besides, new schools and wells are of no use if there is no one to guarantee pupils’ safety and prevent the destruction of these new infrastructures. This issue is linked in part to the French decision, similar to the US one in Afghanistan, not to commit too many ground troops. Indeed, they relied primarily on airpower in order to control large swaths of land at a low material and human cost. Moreover, airpower is politically easier to use as it can be quickly engaged or disengaged. Nonetheless, ground troops are essential in order to hold a territory and gain popular support.

2. Too much importance was given to the army in the state-building strategy for Mali

This part draws from arguments developed by Joe Gazeley’s “The Strong ‘Weak State’: French Statebuilding and Military Rule in Mali” (2022).

France understood the Malian regime’s weakness in 2012-2013 as a military failure to contain and quell the rebellion. That’s why it aimed at bringing security back in Mali by focusing on military support and training with the desired end being “the construction of a central state capable of militarily disrupting rebel organisation in the periphery“.

France identified the absence of coercive elements of the state (courts, police, military) as the country’s main problem. It thus strove to restore them. However, this approach of strengthening the military carries the risk of further destabilising civilian authority.

Historical perspective

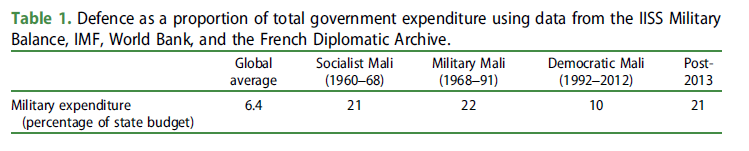

Historically, after the independence of Mali, France was quite satisfied with the predominant role played by the army in the Malian political life. Indeed, it didn’t foster a democratic transition as the level of political stability provided by the Malian army was beneficial to French interests in the region.

Mali got involved in only two armed conflicts since its independence in 1960. It was against Burkina Faso in 1974-1975 and in 1985. There has been an absence of external threat to Mali’s stability, so why is there such a large proportion of state expenditure dedicated to the army compared to other conflict-affected countries ?

This question is even more relevant when we take a look at the 6 coups that occurred since the independence. We understand that the army is actually responsible for most of the political instability that Mali has known since 1960.

Why then did France focus on strengthening Mali’s army and not its political regime ?

It would have required too much time and political efforts to try to improve the Malian political system that France saw as failing, corrupted and incompetent. This frustration of being unable to directly provide a political solution to the conflict might explain why French authorities focused most of their efforts on consolidating the Malian army. As a result, political institutions are still weak and Malian elites lack accountability, legitimacy and popular support.

However, can it be expected from France, a foreign power, to impose a political model in Mali without being accused of neo-colonialism? What would be France’s legitimacy to do so?

Criticisms about France’s over-emphasis on strengthening the Malian military power are acceptable, but what else could it have done? France couldn’t just intervene in Mali to repel terrorists and then simply leave the country while knowing that the same terrorists would come back soon thereafter. It had to try something in order to prevent this crisis from happening again.

Focusing that much on the Malian army was probably not the right choice. It should have been forecast that the Malian army would attempt to seize power, should it got the opportunity.

The whole problem can be summed up as follows. France was called on to solve a security/military crisis in Mali, and it did solve it in the beginning of its intervention. Nonetheless, the underlying reasons for the occurrence of such a crisis lie in the weaknesses of the Malian institutional system. However, France has neither a mandate nor any legitimacy to intervene and change the Malian political regime according to its own norms.

C. A lack of US interest for this region

Senegalese President Macky Sall underlined in February 2022 that “the fight against Islamist insurgencies in the Sahel cannot be the sole responsibility of African countries“. It is also not the sole responsibility of France to act along African countries to address the terrorist jihadist threat in the Sahel. This threat should concern all European countries, to a greater extent than it currently does, and more broadly speaking all Western societies.

The military defeat of Daesh in Syria and Irak has made us forget that other Islamist groups in the Sahel region reject Western values. If not dealt with, they will muster enough resources to eventually plan direct terrorist attacks against Western societies.

The US stance in 2012-2013 regarding the security situation in Western Africa is symptomatic of the lack of attention that was given to this region. Yes, the US territory is not directly threatened by Sahelian groups for obvious geographic reasons and in 2012-2013 the US focus was understandingly put on the Middle East. However, I still find it interesting to describe how they behaved with France in the handling of the crisis. For this purpose, I used Mark Moyar’s “FPI Bulletin: Counterterrorism Lessons From Mali” (2015).

In late 2012, French and US officials discussed the situation in Mali. US authorities promised to provide “whatever it takes” to help France in Mali. However, when France asked for US support invoking publicly the “whatever it takes” pledge, the US asserted that the true meaning of what they said was “lost in translation” and that they “didn’t promise specific support”.

Later, President Hollande asked the Obama administration to provide refuelling aircraft that France didn’t have and that were necessary for its operations. The US said it would do so only if it obtained extensive information on French bombers’ targets. Their inaction lasted several weeks and was justified by the absence of threat for the US homeland.

The same logic could have been used for the US intervention in Afghanistan regarding the geographical distance that separates the two countries. They intervened in Afghanistan because of the 9/11 attacks i.e. after being attacked. If they don’t consider more seriously the threat posed by terrorist jihadist groups in the Sahel and try to act preemptively, they might undergo other terrorist attacks on their soil in the future.

8 Comments

Humiliation in International Relations – geopol-trotters · 17 August 2023 at 2:21 pm

[…] order to guarantee stability and protect their interests after the independences, countries like France in Africa or the US in South-America, the Middle-East and Asia have sought to develop interpersonal […]

RUSSIA: a predator in AFRICA – geopol-trotters · 13 May 2023 at 6:23 pm

[…] as to achieve its goal in Africa, Russia competes with other global powers such as France, the US, the EU, China, Turkey… All of them approach this rivalry as a zero-sum […]

Weak and Failed States in Africa – geopol-trotters · 26 April 2023 at 4:15 pm

[…] certain extent, we can draw a parallel with the presence of the mercenaries of the Wagner group in Mali, Burkina Faso and the Central African […]

UGANDA: the “Pearl of Africa” - geopol-trotters · 31 March 2023 at 7:40 am

[…] Organisation of African Unity created in 1963. It gathers all African countries apart from Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso and Sudan that have been […]

Pan-Africanism, between genuine aspirations and ideological hijacking - geopol-trotters · 18 March 2023 at 12:26 pm

[…] of Mali and Senegal, Alpha Omar Konaré (1992-2002) and Abdoulaye Wade (2000-2012), who denounced Françafrique and spread panafricanist ideas across West […]

Al-Qaeda and Daesh in Africa - geopol-trotters · 1 January 2023 at 4:48 pm

[…] as JNIM’s sanctuary. Indeed, governmental forces are absent from this region inhabited by Tuaregs, which also deter them from intervening there. Besides, exactions committed by the Wagner group and […]

West Africa, a Hotbed of Narcoterrorism - geopol-trotters · 25 November 2022 at 8:45 pm

[…] the French intervention in 2013, there were three main jihadist formations operating in northern Mali: AQIM, the Movement for […]

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC : civil war and Russian predation - geopol-trotters · 5 November 2022 at 6:45 am

[…] to this agreement, mercenaries of Wagner ensure the formation of CAR armed forces. Wagner uses the name Sewa Security Services in CAR. 2,000 […]