Is the BALTIC SEA a “NATO lake” ?

Your 5-minute weekly dose of geopolitics in a straight-to-the-point and illustrated format. Enjoy!

I) NATO is gaining more control of the Baltic Sea, which is a region of major strategic importance

A. NATO reinforces its strategic footprint in the Baltic

With Finland (April 2023) and Sweden (March 2024) joining NATO, now all coastal states of the Baltic — except for Russia — are NATO members. In parallel, the number and scale of NATO military activities in the area have increased. In June 2024, NATO conducted the BALTOPS 2024 exercise (53rd iteration), which mobilised over 50 warships, 9,000 troops, and 85 aircraft from 20 allied countries.

Moreover, the Nordic-Baltic Eight (NB8) — an informal cooperation format comprising Iceland, Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Sweden and Finland — has strengthened regional security coordination to face threats coming from Russia.

B. The Baltic Sea is of strategic importance, hence the competition to control it

The region is home to essential undersea infrastructure, notably telecommunications and power cables that ensure connectivity between Scandinavia, Baltic States, and continental Europe. The Baltic Sea is also a vital trade corridor connecting European markets to the North Sea and the Atlantic. In addition, the sea hosts important natural resources such as fish, oil and gas reserves, as well as wind for energy production.

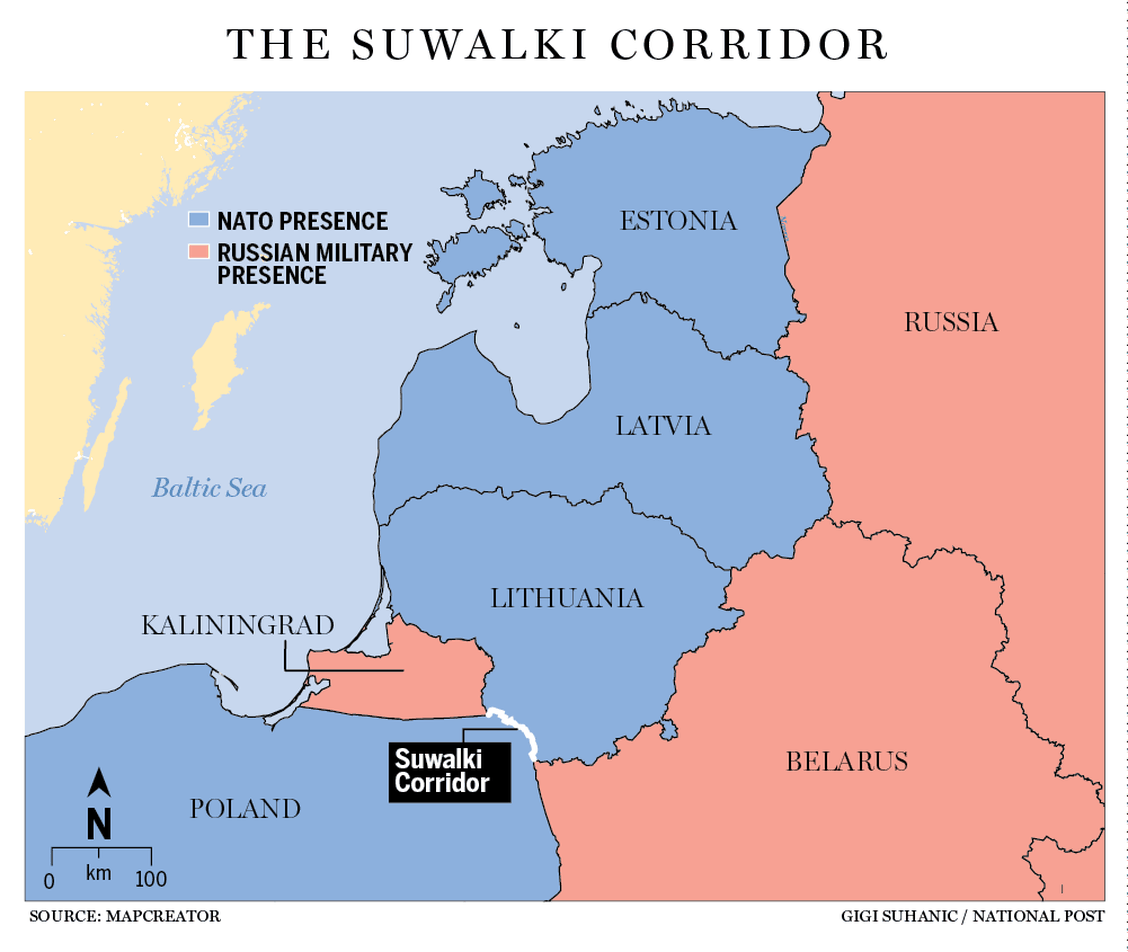

Its strategic dimension makes the Baltic Sea a contested space. Russia’s Baltic Fleet is stationed in Kaliningrad and St. Petersburg. Even though it has never been a priority for Russia — that has focused on its Northern and Black Sea fleets, the Baltic Fleet remains instrumental in asserting Russia’s geopolitical stance in the region.

II) However, NATO does not fully control the Baltic Sea and is likely to face persistent obstacles in trying to do so

A. Russia maintains some freedom of action in the Baltic Sea and carries out disruptive activities in the Baltic Sea

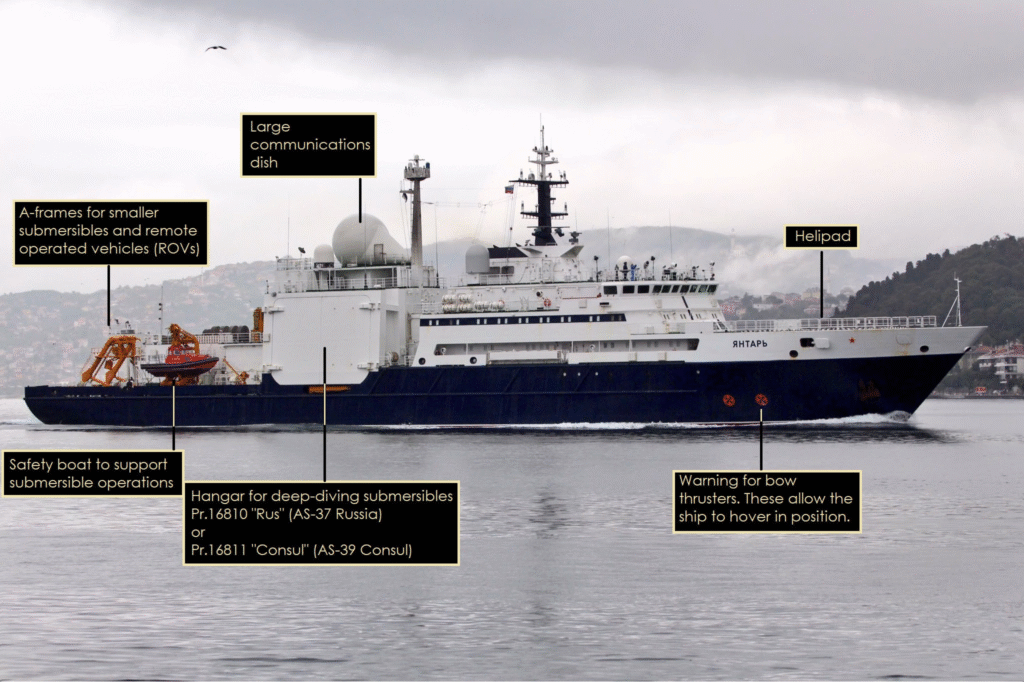

Hybrid operations conducted by Russia continue to challenge NATO’s regional ambitions. For example, in December 2024, Finnish authorities arrested the crew of the Eagle S, which had been spotted cutting undersea telecom cables and engaging in espionage activities. Another such vessel is the Yantar, a Russian intelligence collection ship capable of deploying submersibles and engaging in undersea cable interception. It operates regularly in the Baltic, officially as an “underwater research ship”, and contributes to Moscow’s disruption strategy.

Furthermore, Russia uses a so-called “dark fleet” (aka “shadow fleet”) — composed of ageing oil tankers operating with transponders turned off and often under false flags — to circumvent sanctions and move energy products through the region unnoticed. The US and the EU have imposed sanctions on most of these ships.

B. Control of the Baltic Sea seems out of NATO’s reach

Apart from the fact that Russia retains sovereign rights in the Baltic Sea as a coastal state, the hybrid warfare it wages challenges NATO’s ability to exert maritime control in the Baltic. Indeed, hybrid threats such as espionage, sabotage, or the use of civilian vessels for intelligence purposes are difficult to attribute and respond to. The attribution problem — difficulty in legally proving responsibility for hybrid attacks — weakens NATO’s ability to react with force or sanctions. In such a context, establishing comprehensive and uncontested control over the Baltic remains a complex challenge for the Alliance.

Tensions could escalate in case of Russian actions around the Suwalki corridor or strategic islands in the Baltic Sea such as the Bornholm, the Gotland, or the Aland islands.

0 Comments