Weak and Failed States in AFRICA

This article is partly based on “État fragile, aplati, failli. Réflexions sur la gouvernance hybride et l’évolution de l’État en Afrique et au Sahel”, a study conducted by Thierry Vircoulon and published by the IFRI in September 2022.

What you want to understand: 🤔

- What is a failed State? What factors account for the existence of failed States in Africa nowadays?

- In the DRC, who has replaced the State at the basis of the educational system?

- In Chad, how do rural populations settle property-related disputes?

- In Guinea, why has the State delegated its law enforcement power to hunters?

- In Benin, why is a NGO fighting terrorism in national parks instead of the State?

I. The weakening of states

A. Definition of failed States

Even though the concept of “failed state” is debated, we can try to provide a definition so that everyone’s on the same page. The characteristics of failed States are the following:

- Inability to provide basic public services (education, health, security…) to its population

- Inability to enforce laws, collect taxes and implement policies. They have lost what Max Weber calls the monopoly of the legitimate use of violence. Basic rights and freedoms are no longer protected.

- Widespread corruption/criminality

- Blatant economic inequalities

- Weak political, economic and financial institutions

- Protection of its frontiers and of its population is compromised

Failed States often find themselves in a situation close to anarchy.

B. How are States weakened?

From above, African States are losing their sovereignty because of globalisation, financial speculation, foreign interferences and so on.

From below, (neo)traditional powers, large municipalities, associations, religious groups and warlords, among others, challenge their power.

II. In the DRC, a double-face private sector at the basis of the educational system

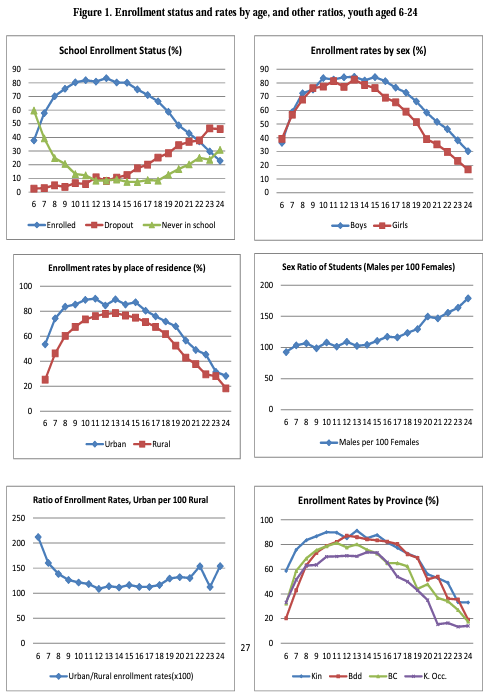

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, religious organisations, mainly catholic and protestant ones, own around 80% of public primary schools. Even though most congolese schools were not free until 2020, the same year the school enrollment rate was at 71%, from 32% in 2000.

Higher education institutions in the DRC are either in the hands of religious organisations or in those of entrepreneurs. In the anarchical development that the sector is experiencing, paying one’s school fees amounts to buying one’s diploma.

In 2020, in order for education to be a public good accessible to all young Congolese, the government made primary and secondary schools free. Nonetheless, this attempt met with little success as many teachers didn’t receive their salaries. Some parents even paid “motivational fees” to teachers.

The governement also closed several schools deemed not viable so as to clean up the sector. Nevertheless, the latter remains plagued with many institutions seeing Congolese demographics solely as a business opportunity.

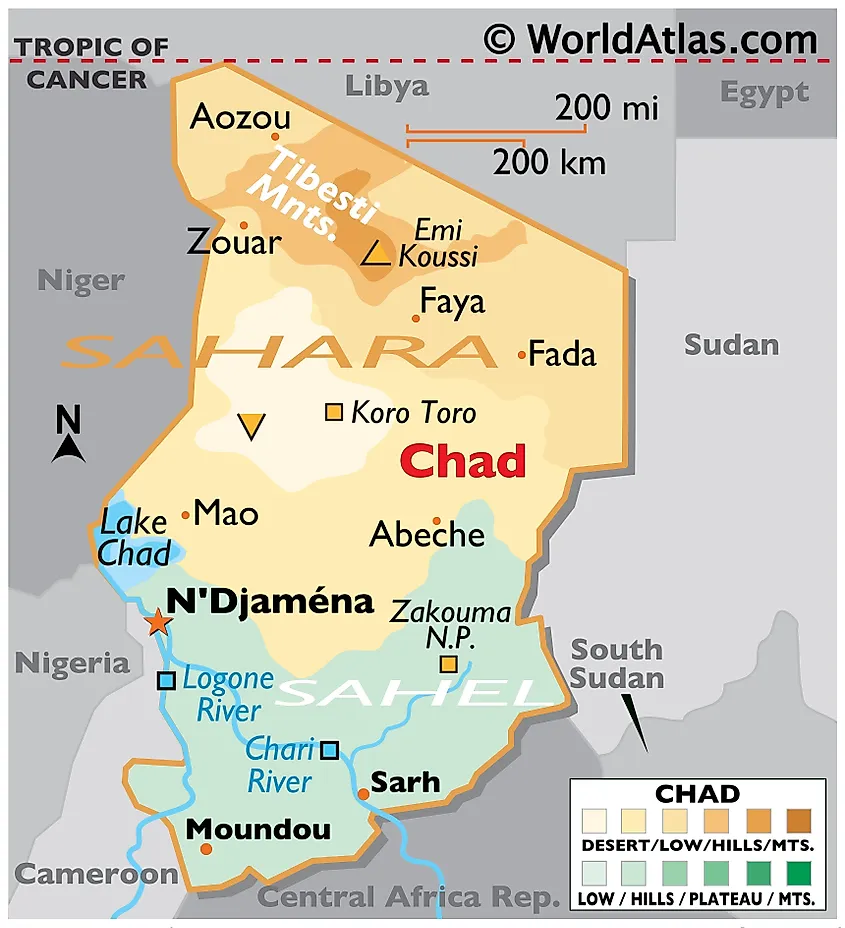

III. In Chad, a justice without judges to settle rural property-related disputes

In Chad, when property-related disputes arise in rural areas, it is rarely to state judicial institutions that populations turn. The reasons are the following:

- It is far too expensive for poor rural populations to resort to the judgment of a court

- Judicial and administrative state institutions are not always present in remote areas

- Corruption is widespread, which reduces trust in decisions

- A long administrative process often precedes the settlement of disputes over natural ressources. In fact, for this kind of cases, courts summon technicians from various fields of expertise to analyse the situation and help them make an enlightened decision

As a consequences, and in accordance with the law, local traditional chiefs often become administrative collaborators who manage local properties and tensions related to them, especially between cultivators and pastoralists.

Most of the time, rural inhabitants in Chad resort to mixed mediation committees to dispense justice. These local committees are made up of traditional leaders and representatives of various interest groups like cultivators and pastoralists. They are easily accessible due to :

- Low costs

- A presence in remote areas

- Trust created through proximity between citizens and these ad hoc judges

IV. In Guinea, the ambivalent impact of hunters as security auxiliairies

In Guinea (Conakri), Donzos are tradtional hunters who provide villages with meat and ensure the protection of people and properties. For several years now, they have been used as auxiliairies and sometimes even as substitutes of police forces.

In 2009, Guinea’s National Union of Traditional Hunters and Healers was created to set a judicial frame around their law enforcement activities. This neo-traditional structure is able to meet the security needs of rural populations that cannot rely on the State. The latter thus loses its monopoly of the legitimate use of violence. However, it is worth noting that, in cities, Donzos have already been deployed several times as an anti-protest force to quell political claims against the regime.

Using Donzos for security purposes at the national level is a factor of instability for the following reasons:

- Warlords lead these groups and their allegiances are multiple, mercurial and sometimes ambiguous

- Donzos engage into poaching

- Donzos fight along the Malian border to get hold of artisanal gold-bearing mines

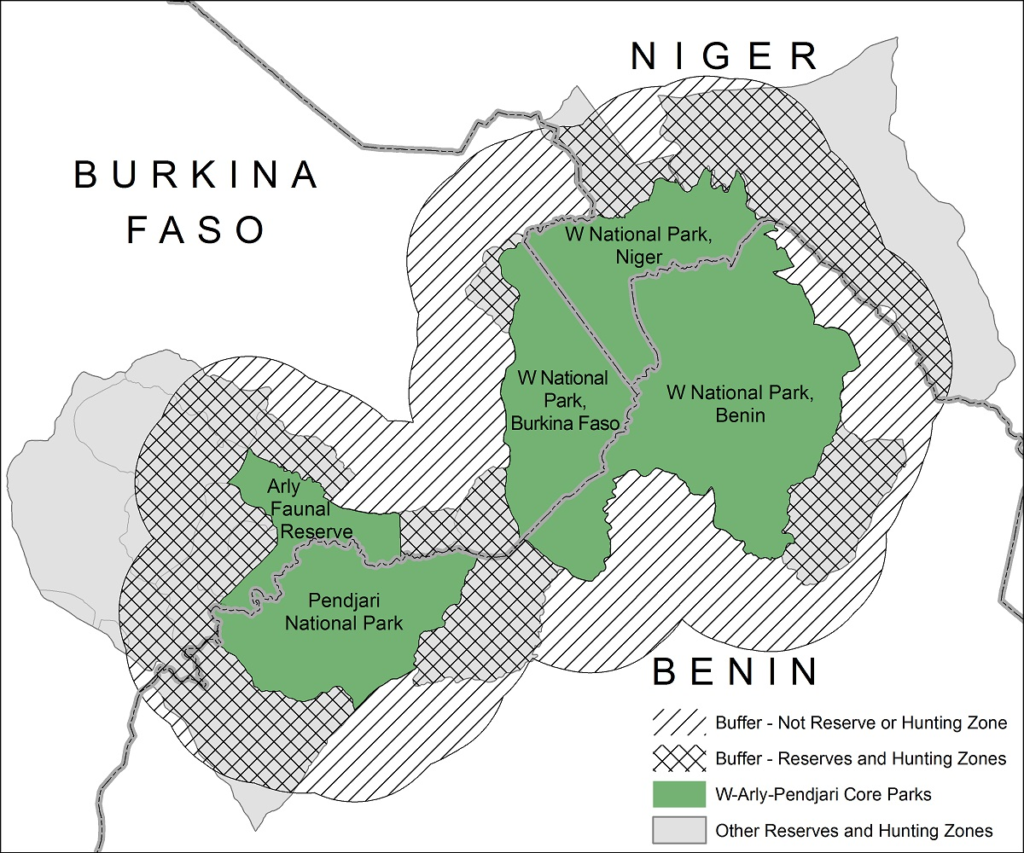

V. In Benin, a NGO is in charge of fighting terrorists in national parks

In a context where terrorist groups seek to expand to the Gulf of Guinea, parks W, Arly and Pendjari have become sanctuaries for them. Group Arly and group Abou Hanifa are respectively present in Arly and in W and Pendjari.

This area is optimal for jihadist terrorist organisations to grow thanks to:

- The presence of resources

- Weapons, ammunitions, motorcycles and fuel are smuggled by cross-border criminal networks

- Gold-panning sites

- Poaching and ivory trafficking

- Tensions between communities of cultivators and pastoralists

- Tensions between the State and its citizens e.g. hunting/fishing for subsistence has been forbidden

- Upon their arrival, terrorist groups reinstated these practices, which increased their popularity

- High potential for recruitment with the presence of Fula people (a pastoralist and nomadic minority group discriminated against in many Sahelian countries)

Due to Benin’s shortcomings and inability to coordinate efficiently with its neighbours, the South-African NGO African Parks Network (APN) has been entrusted with carrying out counter-terrorism missions in the area. APN is a major security sub-contractor in Western Africa. It already manages 22 protected areas in Africa and has for objective to reach 30 by 2030.

In Benin, APN has a mandate for the 2017-2027 period to develop ecosystems, tourism and the local socio-economic situation. Due to its arbitrary and violent approach, local populations protested, which forced the South-African NGO to adapt its modes of action. It now hovewer chiefly focuses on counter-terrorism. As a matter of fact, Benin has delegated a part of its sovereignty in order to ensure the protection of its population and territory.

APN doesn’t conduct large-scale operations deep in the parks or close to frontiers, which leaves a great deal of leeway to terrorists. Instead, APN carries out police, securisation and monitoring missions on parks’ edges. Rangers also patrol jointly with Benin security forces and share an intelligence centre with them.

What is rather striking is that the NGO’s operational capabilities are much more developed than those of State forces. For instance, their equipment includes air and naval means of communication and surveillance whose efficiency far exceeds those of Benin.

However, APN’s actual impact on the security situation in the area remains rather marginal.

To a certain extent, we can draw a parallel with the presence of the mercenaries of the Wagner group in Mali, Burkina Faso and the Central African Republic.

VI. Comments and analysis

A. The issue with formalising the coproduction of public services

A State formalises the coproduction of public services with another entity with administrative stamps.

What has been noticed is that the price of these stamps is inversely proportional to the adminsitration’s efficiency. In other words, States that poorly administrate their country tend to charge a higher price to entities that want to coproduce public services.

Furthermore, those who get these administrative stamps tend to abuse their authority. That’s why we can witness custom officers who muggle, soldiers who side with rebels, police officers who collude with criminals and so on.

B. Power sharing between legitimate and illegitimate actors

In conflict areas, the ad hoc collaboration between warlords and local authorities, whether they are traditional, religious, administrative or economic, allows for policing territories and managing local affairs such as local tax collection, transhumance, vaccination…

C. Social hierarchy inversion

The coproduction of public services implies that the mercantile class rises in the social hierarchy while the class of public servants tends to drops. Public servants have been the elite of these African country since the end of decolonisation but now they get more competition at the top of the hierarchy. Nevertheless, we should bear in mind that overall public institutions remain idealised and feared by large proportions of the populations.

D. Foreign financial aid

This foreign aid is rather ineffective when it comes to restoring order in the functioning of States and supporting the implementation of reforms.

However, it allows to restore an equilibrium in terms of budgetary capability between the State and non-state actors. As a matter of fact, the latter often have more financial means at their diposal, which accounts for their ability to take over the State to provide public services to populations and then make benefits out of it.

Furthermore, foreign financial aid allows States to finance their payroll and thus prevents their disappearance as employers.

1 Comment

SOMALIA: al-Qaeda’s base in Eastern Africa – geopol-trotters · 5 June 2023 at 7:16 am

[…] Somalia is deemed a failed state, Somaliland enjoys some degree of economic development and political stability. Nevertheless, […]