Where is IRAN heading?

In 2003, the revelation that Iran had been building undeclared nuclear facilities sparked what became known as the Iran nuclear crisis. Subsequently, the international community imposed sanctions on Iran from 2006 onwards for the country was violating its commitments under the 1968 Non-Proliferation Treaty, which it joined in 1970. The UN Security Council lifted sanctions in 2015 after the conclusion of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), under which the USA, China, Russia, the UK, France and Germany could monitor Iran’s nuclear programme and ensure, with the assistance of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), that it remained exclusively civilian in nature. However, the USA withdrew the agreement in 2018 and reimposed sanctions on the Iranian regime. The recent escalation of hostilities with Israel has reignited intense debates in Iran over whether the country should acquire nuclear weapons.

I) Iran has faced various setbacks that have undermined its operational capacities (A) and its diplomatic standing (B)

A. Operational setbacks

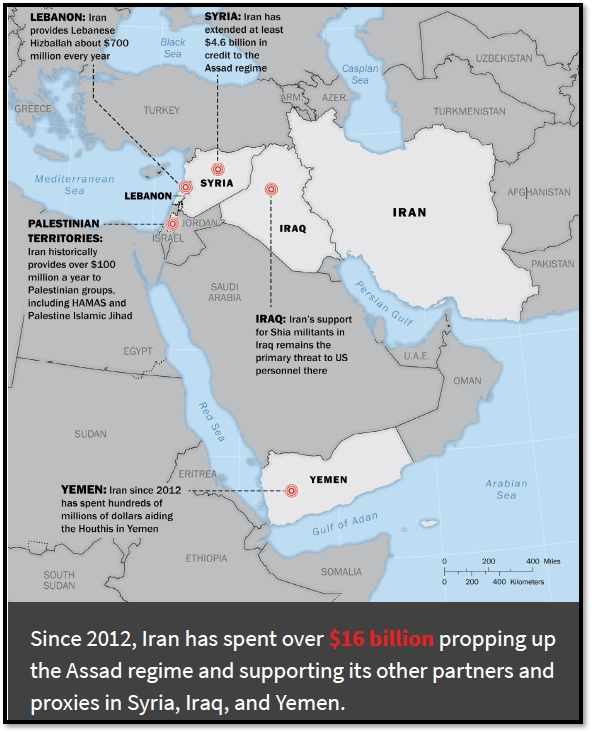

The months and years following Hamas’s attack on Israel on 7 October 2023, Iran has seen its regional proxies collapse one after another:

- Gaza: Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad have lost most of their leadership, equipment and tunnel infrastructure

- Lebanon: Hezbollah‘s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, was killed by Mossad in September 2024, and the organisation has lost a significant proportion of its arsenal

- Syria: Bashar al-Assad’s regime was overthrown in December 2024 by Ahmed al-Sharaa’s HTS, which has hampered Iran’s ability to supply Hezbollah with equipment from Iraq through Syria

- Iraq: the Popular Mobilisation Forces are under heavy pressure from the USA

Apart from the Houthis in Yemen – who are considerably more autonomous and resilient, Iran can no longer rely on its regional proxies to assist it in the event of an aggression, let alone to project power abroad.

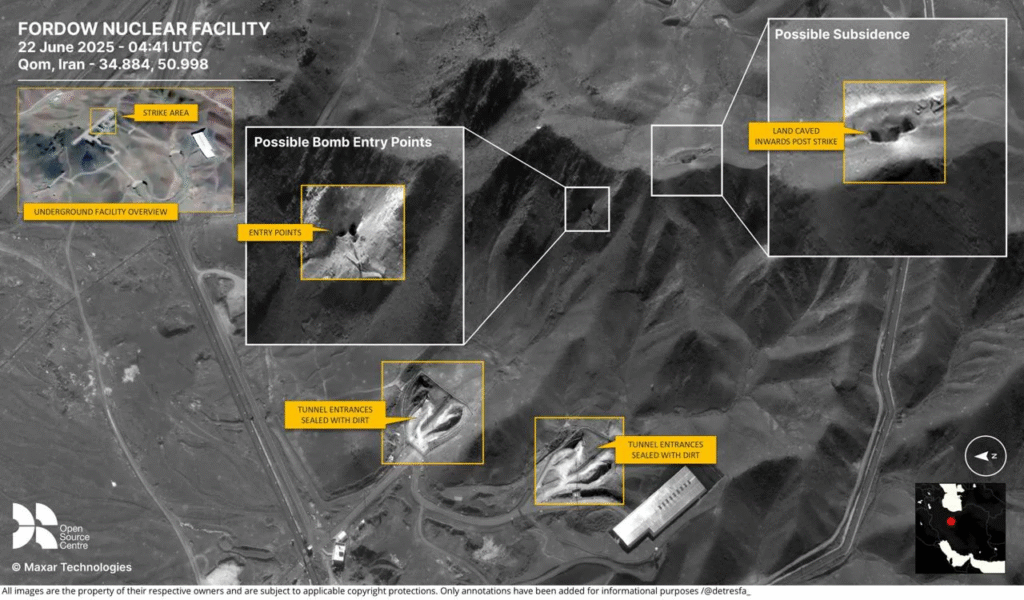

Additionally, during the 12-Day War in June 2025, Israel and the USA jointly targeted Iran’s nuclear facilities at Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan. These preventive strikes have delayed Iran’s nuclear programme for several months, although the regime still retains approximately 450kg of uranium enriched to 60%.

B. Isolation on the global stage

The reimposition of US sanctions in 2018, following Washington’s withdrawal from the JCPOA, has further deepened Iran’s isolation on the global stage. This decision had a tangible impact on the Iranian economy: while its GDP growth reached +9% in 2016 – a year after the lifting of international sanctions, it contracted by 3% in 2019.

This international isolation has intensified recent years. Firstly, Russia and China – which had signed strategic partnerships with Iran in January 2025 and 2021 respectively – remained passive as Israel and the USA targeted Iran’s nuclear facilities in June 2025. Secondly, the E3 countries (France, the UK, and Germany) activated the snapback mechanism in September 2025 to reimpose the international sanctions that had been lifted in 2015, arguing that Iran had failed to comply with its obligations under the JCPOA.

II) Iran may now seek to achieve nuclear territorial sanctuarisation (A), while deepening its integration with the Global South to overcome its isolation (B)

A. Acquiring nuclear weapons, the only option left?

Since 2019, Iran has enriched its uranium stockpile to such an extent that, by 2022, it had become a “nuclear threshold state” – possessing the infrastructure, technology, expertise, and material necessary to rapidly build a nuclear bomb. Tehran, however, chose to refrain from crossing the nuclear threshold, pursuing instead a hedging strategy. This approach has consisted in using the threat of becoming a nuclear power as leverage in negotiations with the West to secure an agreement that would lift international sanctions and provide more favourable terms than the JCPOA.

However, the joint Israeli-American strikes on Iran in September 2025 signalled the failure of the “hedging strategy”. Indeed, both Washington and Tel-Aviv have categorically refused to negotiate any deal with Iran as long as it remains a nuclear threshold state.

Consequently, Iran may now decide to accelerate its military nuclear programme in order to acquire the bomb and deter any further aggression.

This course of action may be reinforced by the regime’s growing perception that it can only rely on itself for its own security. Neither Russia nor on China can offer credible security guarantees, and Iran’s regional proxies have become too weak.

As the survival of the regime remains Iran’s leaders’ paramount concern, the nuclear sanctuarisation of the Iranian territory appears to be their most likely next step in a context of heightened geopolitical tension.

B. Diplomatic efforts towards the Global South

In order to overcome its international isolation, Iran is likely to intensify its efforts to integrate more deeply with the Global South.

Tehran has already joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in 2023 and the BRICS+ in 2024. It also regularly conducts joint military exercises with Russia and China like in March 2025 when their navies participated in the Security Belt 2025 naval exercise off the coast of Oman. Moreover, Iran seeks to strengthen its trade ties with Russia and India within the framework of the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC), which remains largely at the project stage for now.

0 Comments