RUSSIA-CHINA: friends to enemies?

Here are the main takeaways of my reading of two articles on the relationship between Russia and China:

- A Lame Alliance of Victory: Although Beijing and Moscow are still closely cooperating, the Russia-China alliance looks unstable and vulnerable (Re:Russia, 08/05/2025)

- Amid the war, Russia has grown even closer to China. Are Putin and Xi Jinping now going to “fight the collective West” together? Sinologist Temur Umarov explains why the two countries’ relations are much more complicated than they seem (Meduza, 02/04/2024)

In the early 2010s, Vladimir Putin’s Russia initiated a “Pivot towards the East”, in particular towards China. This strategic shift from Europe to Asia became a central aspect of Russia’s foreign policy following the invasion of Crimea in 2014 and its 2015 intervention on Bashar al-Assad’s side in Syria. Indeed, Russia fell under Western sanctions and found itself more and more isolated on the global stage. That’s the moment when it sought to consolidate its participation in the BRICS and deepen its relation with China, as it was looking for partners sharing the same rejection of the Western-dominated world order.

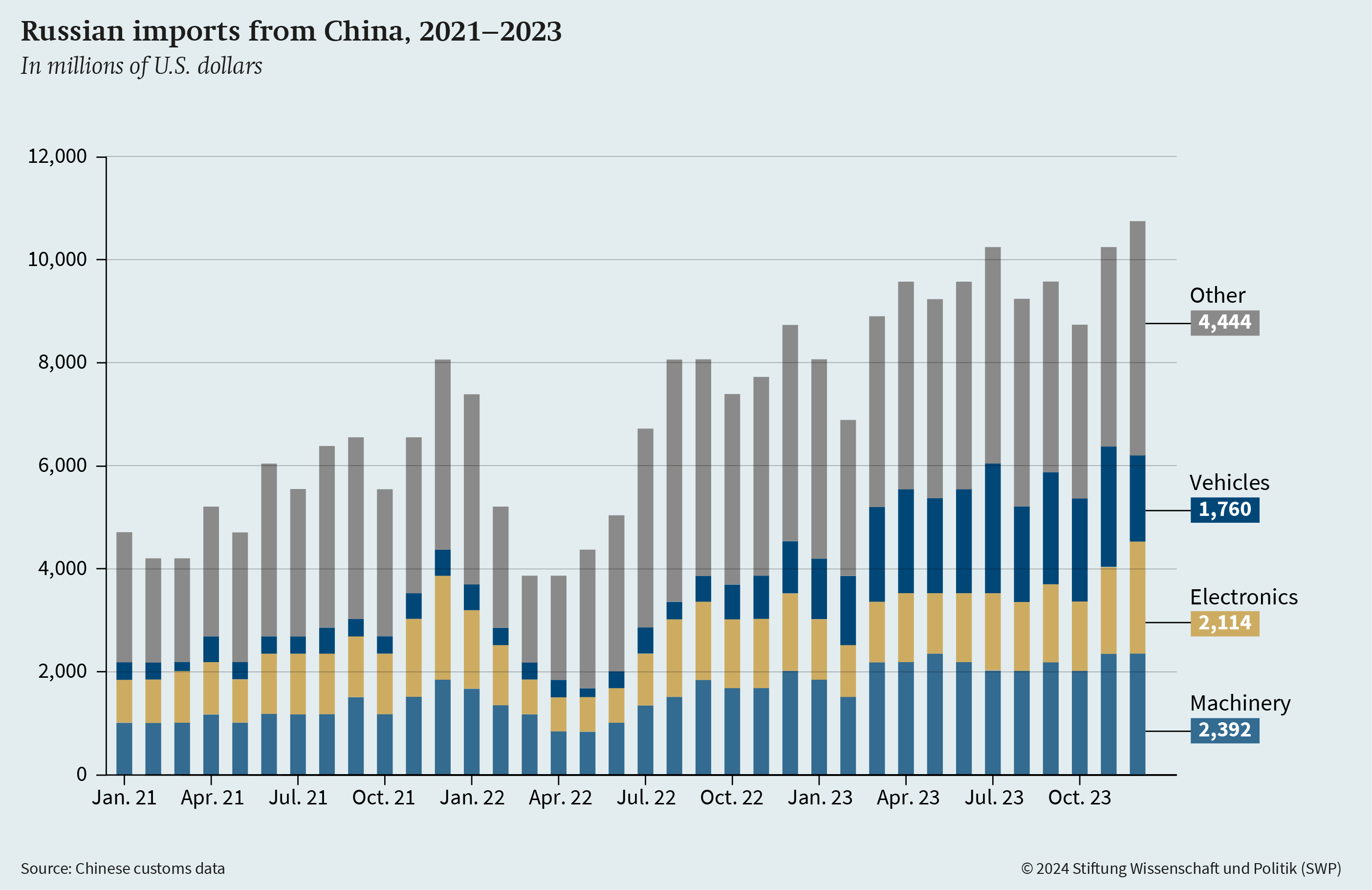

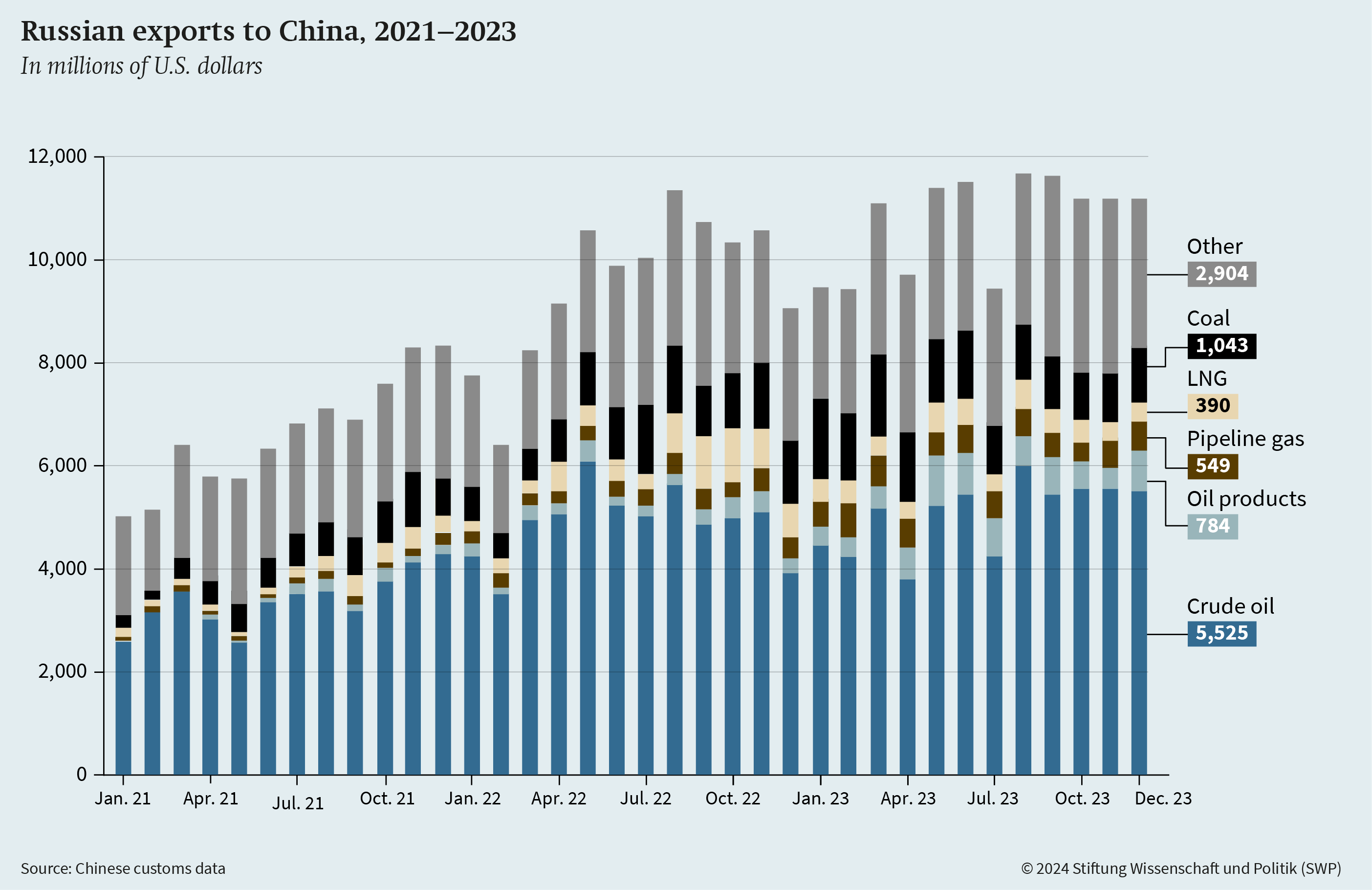

The rapprochement between Russia and China became unequivocal in the context of the war in Ukraine. Its main indicator is trade exchanges : they surged by 63% between 2021 and 2023.

On the day of President Donald Trump’s inauguration, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin called each other as a symbol of their mutual commitment to stand shoulder to shoulder in the face of future challenges from the new American administration.

At first glance, their association seems logical and even unavoidable. Indeed, both Russia and China share common characteristics such as State control of public and economic life, the rejection of Western political and cultural liberalism, and the will to change the global balance of power.

However, the Sino-Russian relation is far from being as strong and resilient as some like to portray it. Let’s explore the vulnerabilities and limits of the relation between these two global powers that can definitely not be put on an equal footing.

STILL A “NO-LIMITS FRIENDSHIP”?

In 2022, before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia and China described their relation as a “no-limits friendship”. However, they actually never used the term “alliance”. As a matter of fact, they purposefully avoid calling themselves “allies”. They only talk about a “partnership” and use less and less the term “friendship”. With regard to China, it doesn’t want to be drawn into the war in Ukraine and perfectly knows that it will never be able to control or predict Vladimir Putin’s decisions. As for Russia, its “Pivot towards the East” includes the entire Asia-Pacific region, which implies establishing partnerships with countries like India and Vietnam. In order not to antagonise the latter that have feuds with China, Russia avoids conveying the idea of a close and unshakeable alliance with China.

ASYMMETRIC TRADE IN FAVOUR OF CHINA

The main threat to the relation between Russia and China is the high level of asymmetry in favour of the latter, which can lead to distrust and resentment, as we will see further down this article.

This asymmetry became obvious with the war in Ukraine. Russia was sanctioned and isolated by its West trade partners. It had no alternative but to get closer to China. In fact, China represents 35% of Russia’s foreign trade exchanges, which is approximately Europe’s share before the war (now 11%). China’s share before the war was around 18%.

Their trade exchanges can be described as Russian raw materials in exchange for Chinese manufactured and high-tech products. In 2024, 78% of Russia’s exports to China were raw materials, and around 60% of Russian imports from China were manufactured and high-tech products.

As a matter of fact, with the end of European manufacturers’ activities in Russia, China has consolidated its integration in the Russian market. For instance, 60% of car sold in Russia are now Chinese. However, this results in a fierce competition for Russian companies that see their market shares shrink.

CHINA BRINGS RISK, NOT CAPITAL, TO RUSSIA

It’s not because Chinese goods are flooding the Russian consumer market that China will invest and set up factories on Russian soil. In fact, China regards Russia as a short-term consumer market with a high demand but not as a long-term investment. It is partly due to the fact that there is too much uncertainty surrounding the future of the Russian economy. There is also the fear of Chinese investors to fall under secondary sanctions imposed by the West.

Chinese investments in Russia represent less than 1% of the Russian GDP. In contrast, it’s 4% in Kazakhstan, 15% in Turkmenistan and 50% in Mongolia. As a matter of fact, usually the Russian industries that need capital are not those in which Chinese investors wish to put their money.

Additionally, China does not seem eager to invest in major Russian projects such as the Baikal–Amur Mainline (BAM) or the Trans-Siberian Railway. Actually, the currently low level of Chinese FDI does not show signs of improvement for the coming months and years.

Moreover, Russian foreign-exchange reserves contain more and more renminbi since Russia has increased its trade exchanges with China and reduced its interactions with Western partners that trade in dollars, euros or pounds sterling. However, it puts the Russian financial structure at risk because China sees the renminbi as a trade and industrial tool that it can manipulate according to circumstances.

RUSSIA’S GEOPOLITICAL CONCESSIONS

China’s expanding sphere of influence is progressively encroaching on Russia’s “Near Abroad”, particularly within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative launched in 2013. In fact, China expands its influence in Central Asia while Russia is focused on Ukraine. There has been a 27% increase in trade between China and Central Asia over the course of 2022-2023. Besides, China invests more and more in Central Asian raw material industries and participates in cross-border projects such as the railway that links it with Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Moreover, the cooperation with the region in the realm of security and defence is also expanding within the framework of the Chinese Global Security Initiative (2022). However, it is worth noting that China doesn’t enjoy the same level of trust as Russia amongst the populations and elites of Central Asian countries.

In Africa, China takes advantage of Russia’s informational warfare that pushes Western powers out of the continent. Nonetheless, Russia doesn’t have the economic means to compete with China in Africa or in other regions such as the Balkans. Therefore, it has to make concessions on its geopolitical ambitions.

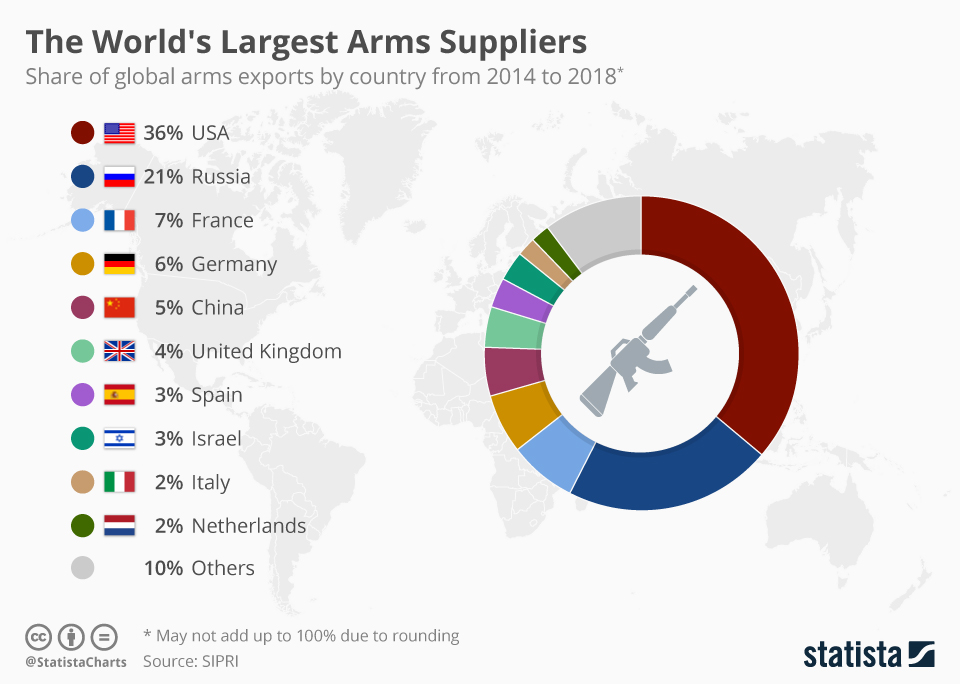

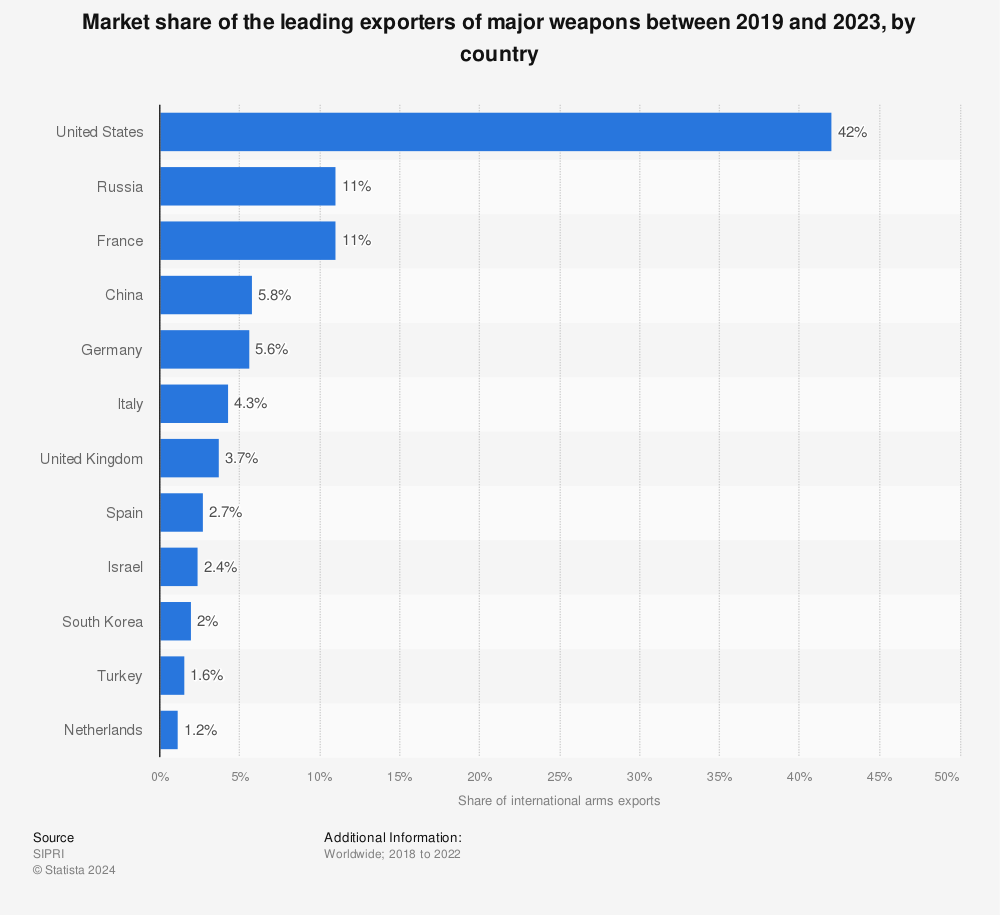

AN INVERSION IN THE MILITARY COOPERATION DYNAMIC

While in the 2000s China imported substantial quantities of Russian weapons, it has since changed its approach and seeks to develop its own military-industrial sector. Moreover, tensions with Russia emerged when the latter realised that China did reverse engineering on its weapons and stole industrial and technological secrets.

Regarding joint military exercises, it’s now China that is taking the lead in their organisation. They take place more and more on Chinese soil with Chinese equipment and with the presence of a majority of Chinese commanders. As a matter of fact, apart from China (Iran and North Korea), Russia does not have many alternatives to take part in large-scale military exercises.

“CHINESE RESENTMENT” IN RUSSIA?

Sinophobia used to be widespread in Russia during the Brezhnev era. It re-emerged in rural areas of Eastern Russia after the collapse of the USSR. It is only in the mid-2010s, when tensions were mounting with the West, that Russia started perceiving China as a potentially close ally. Nowadays, with the war in Ukraine and the ensuing international isolation of the country, the Russian population considers China as their strongest support.

However, there is currently a slight trend indicating growing resentment and dissatisfaction with the conditions of the partnerships with China. Russians still consider their country as a major international power with more influence than China, and they don’t consider themselves as the “junior” in their relationship with China. Therefore, the Sino-Russian relation could deteriorate significantly if Russian elites feel that the attributes of Russia’s power that underpin its international status — influence in its Near Abroad, military might, oil and gas resources, and Russian language and culture — are being devalued or threatened by China.

0 Comments