Has the world entered a “NO WAR, NO PEACE” era?

“The Long Peace” has been used to refer to the period that extends from the end of World War II to the present day as no war has opposed frontally the world’s great powers. Indeed, war is defined both as the absence of peace and as the intense, protracted and organised fighting between two or more armed groups. Conversely, peace is understood as the absence of war. It can also be described as harmony and the orderly resolution of contentious interests (K. Boulding, 1978). Likewise, for Carl von Clausewitz in “On War” (1832), peace can be regarded as a situation in which a certain equilibrium of forces prevents the emergence of violent modes of rivalry. The US has played a primary role in structuring this global balance of power in which the West i.e. North America, the European Union (EU), the United Kingdom, Israel, Japan, South-Korea, Taiwan, Australia and New Zealand, dominates. This world order has ensured a period of relative peace since the end of WW2 and that’s why the “Long Peace” is also known as Pax Americana. However, war still rages in various parts of the world like in Ukraine, Palestine, Syria, Sudan, the Sahel or Myanmar among others.

In this essay, we will argue that to make a world free from wars (“no war”), the West has created an international order that has actually fostered the development of “weakness politics” and of unconventional warfare, thus jeopardising peace prospects globally (“no peace”).

First of all, we will study the reasons why from a Western perspective the world has been freed from war. Then, we will see that to do so the West under US leadership has created a world order based on humiliation, which has eventually led to a shift of the warfare paradigm. Eventually, we will study how this evolution has put into jeopardy peace prospects both in conflict-torn regions and in Western societies.

I. No inter-State war between major world powers

The world seems to have been freed from wars compared to the pre-WWII era, which can be explained by various factors that have considerably reduced the probability and prospects of inter-State wars.

***

Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the world was expected to turn more peaceful as it became more democratic, globalised and nuclear.

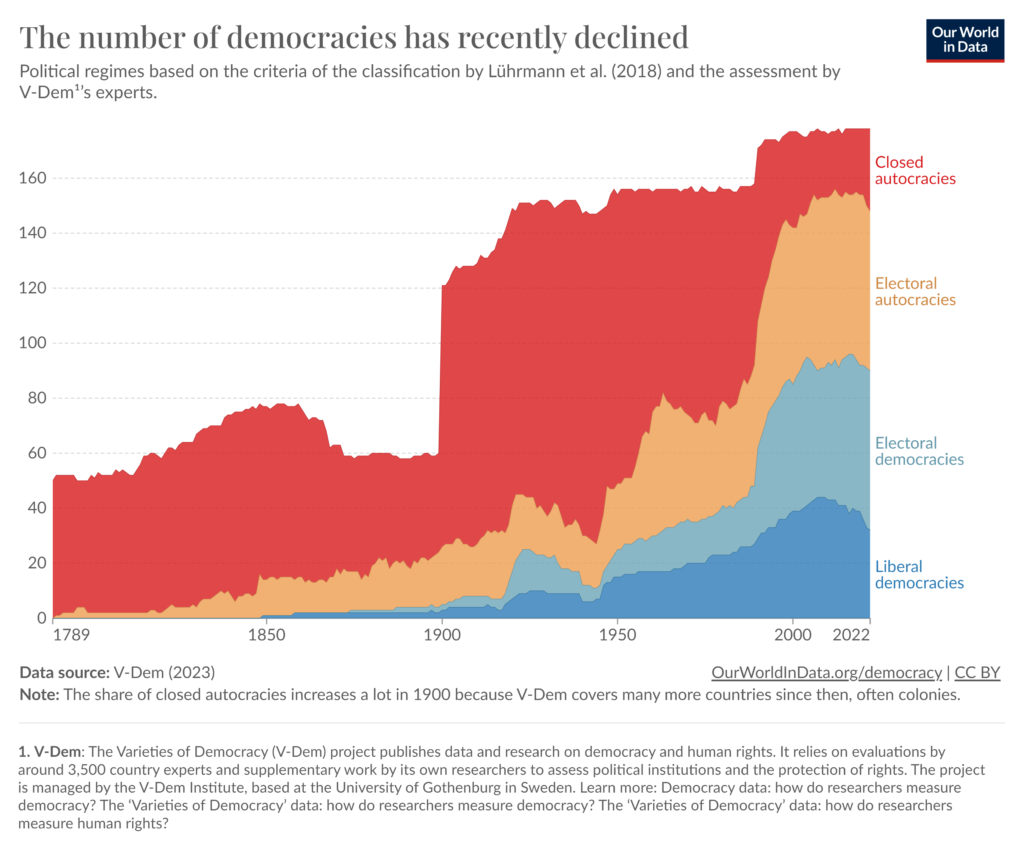

In 1992, Francis Fukuyama announced the “End of History” i.e. the victory of liberal democracies as the ultimate form of government. The ensuing surge in the number of democracies in the world (V-Dem, 2023) was accompanied by the idea that democracies don’t go to war or fight each other, unlike authoritarian regimes that are warmongers. Hence expectations for a pacification of international relations and a reduction of the probability of war.

Besides, with the intensification of globalisation through the liberalisation of exchanges, under the auspices of the US and the World Trade Organisation created in 1995, economies became more interdependent, which made the prospect of war highly undesirable.

Moreover, since the end of WWII, the possession of nuclear weapons by the world’s great powers (the US, China, Russia, the UK, France, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea) has resulted in a balance of terror that has prevented the development of open wars between them given that it would lead to a Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD).

***

Since the end of WWII, the world has experienced fewer inter-State wars and none between its “central powers”, namely countries at the centre of the international system such as G20 members. Moreover, conflicts take predominantly place in “peripheries”, in what is commonly, and controversially, called the “Global South” i.e. the developing and emerging regions of the world, particularly the Middle-East, Africa and Asia and Oceania (Our World in Data, 2023). With regards to the war between Ukraine and Russia, it is indeed an inter-State war but that is located at the periphery of Europe, just like the war between Azerbaijan and Armenia. And even though the US and the EU clearly support Ukraine against Russia, major global powers do not oppose each other frontally in this conflict.

Democratisation, economic integration and nuclear weapons can explain the pacification of societies, but another factor should be reckoned with when trying to understand the relative absence of inter-State wars. Indeed, as Bertrand Badie argues in 2018, there no longer is a Westphalian order with few States with relatively equal power. Instead, there is a global system of dissimilar actors, including non-State ones, that have deeply unequal power capacities. As a matter of fact, power rivalry has been replaced by a strong power inequality, with the US becoming a hegemon after the Cold War. Consequently, it has prevented the development of wars as a manifestation of power competition between States. Hence the idea that the world is experiencing a “long peace”.

II. A humiliating world order and the development of “small” unconventional wars

For this apparently free-from-wars world to exist, there has to be a global balance of power such that there can be no power rivalry that could turn into war. However, the ensuing hierarchy and humiliation cause violent forms of resistance that sometimes develop into what Clausewitz calls “small wars”.

***

According to Zbigniew Brzezinski in “The Grand Chessboard” (1997), the most important for the US after the end of the Cold War was to confirm their world supremacy as it no longer had any rival. To do so the US endeavoured to establish global peace i.e. shape a certain balance of power that would prevent the outbreak of wars.

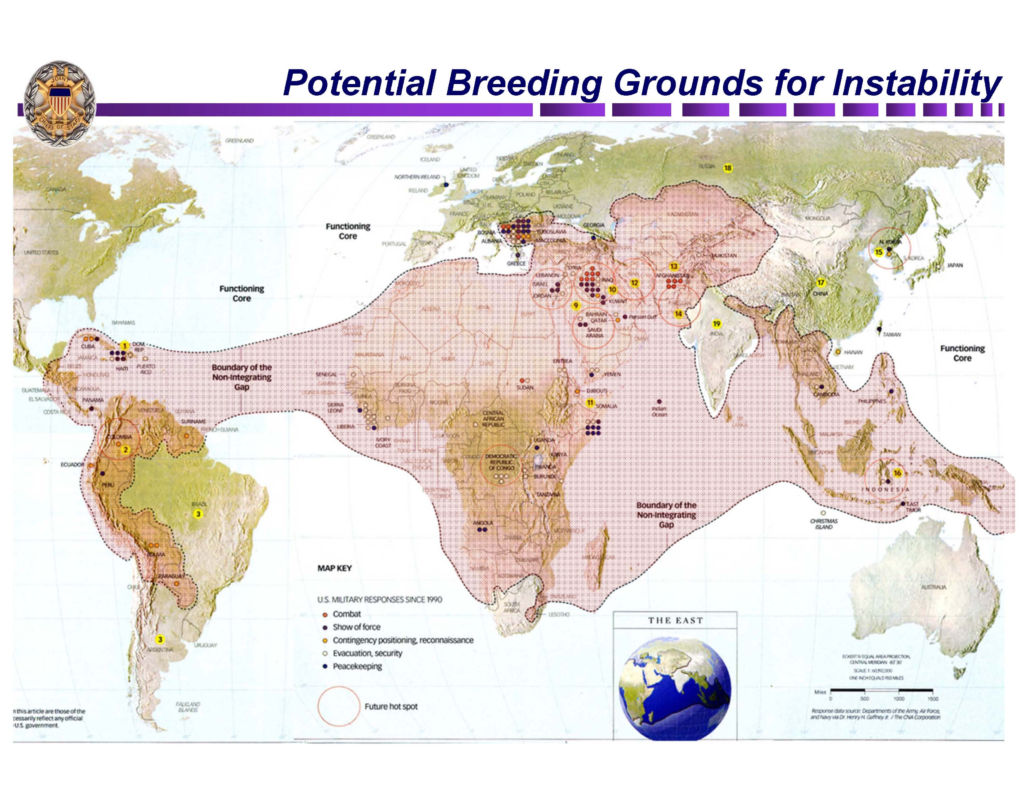

This peace works like a system of inclusion and exclusion (N. Polat, 2010) whose hierarchy is dominated by the West. In 2003, as the US was about to invade Iraq, the American strategist Thomas Barnett developed a theory dividing the world between a US-led “Functioning Core” that is stable, secure and rich, and a “Non-Integrating Gap” that is unstable, dangerous and poor. They only differ in their level of integration into globalisation. In fact, a country’s level of development is measured with a “Western yardstick” as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn already pointed out in 1978 in his Harvard “Commencement Address”.

This hierarchical vision of the world leads to a stigmatisation of those (State and non-State actors) who cannot integrate diplomatically, economically or culturally the Western peace system. The frustration of being maintained in an inferior status is felt as a humiliation (Bertrand Badie, 2014) that can morph into violent forms of resistance against the world order imposed by the West.

***

The exportation of Western norms and values (and interests) to the rest of the world, through international organisation (e.g. UN, WTO, IMF, NATO, EU), operations of influence (e.g. Colour Revolutions) or “just wars”, has faced rejections and failures leading up to wars of an unconventional type.

For example, the ideology of terrorist jihadist movement is rooted in Salafism since it promotes a return to an allegedly golden age in rejection of Western modernisation. Likewise, the exportation of the Western political model failed to adapt to local realities, which created weak and failed States like in Somalia unable to prevent instability, insecurity and ultimately war. For example, in Mali, the hyper-centralised governance inherited from French colonisation failed to reckon with the local cultural diversity. In fact, elites in Bamako monopolised power and favoured certain communities like the Dogon and the Bambara at the expense of the Fula in central Mali and they also antagonised certain Tuareg communities in the North. By doing so it created the conditions for the outbreak of a civil war in 2012, which then turned into a jihadist insurgency playing on inter-community tensions.

The impossibility to integrate the world order, due to rejection or due to an incompatibility of norms and values, and then the impossibility to frontally challenge this world order at the State level by waging war have led the “marginalised” to adopt an unconventional form of warfare that is constitutive of “weakness politics”.

The war between the Taliban and the US in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2021 epitomises this unconventional, and now most common, form of warfare. Indeed, Afghan insurgents waged a war of attrition consisting in harassing their opponent with guerrilla operations to exhaust it. In “On War” (1832), Clausewitz calls these guerrilla wars “small wars” as they are made of small-scale attacks that are part of a wider organised campaign with clear political objectives. One may adopt irregular warfare methods so as to avoid a frontal choc with an enemy that would rapidly annihilate them due to an important power asymmetry. Indeed, unconventional warfare is constitutive of “weakness politics” (Bertrand Badie, 2018) since, given that one cannot compete for power due to one’s relative weakness, it is a way to challenge power. In fact, “weakness politics” has been effective in disrupting the international order as it has led to the banalisation of the weak winning over the strong: wars of decolonisation, warlords in Somalia against the US in 1992-1993, the Taliban in Afghanistan, jihadism in the Sahel…

It is worth noting that one of the main characteristics of unconventional warfare is the involvement of non-State and civilian actors, which is why General Sir Rupert Smith qualifies it as “wars amongst the people” in “The Utility of Force” (2005). That’s why, nowadays wars happen more at an intra- and sub-State level rather than at an inter-State one.

III. The weakening of peace prospects both in conflict-torn regions and in the West

We have seen that the Western domination of the world order has sparked violent reactions under the form of “small” unconventional wars constitutive of “weakness politics”. This paradigm shift in the modes of resistance has significantly reduced the likeliness of achieving peace in the “Global South” and of preserving it in the West.

***

Given the new warfare paradigm based on “small” unconventional wars waged by multiple non-State actors, peace seems highly unlikely to be negotiated and sustained in war-torn countries.

Indeed, the longer a war lasts, the more insurgents reinforce their status of legitimate defenders of their nation against foreign invaders. Besides, violence entrepreneurs (Bertrand Badie, 2018) like warlords, terrorist organisations, private militia or gangs have no interest in negotiating peace as it would deprive them of their raison d’être: they thrive in unstable environment where they act both as agents of terror and as merchants of security, which allows them to control people and territories. Moreover, peace negotiations with them tend to follow a Westphalian logic revolving around issues like control of a territory, disarmament and sanctions. However, a violence entrepreneur has neither de jure sovereignty on a territory nor on a population and, as it does not represent them legally, it cannot commit them in any negotiation. It is worth noting as well that States are reluctant to negotiate with non-State actors for it would put them on an equal footing.

Another factor that makes peace hardly reachable due to the new warfare paradigm is that peacemaking (i.e. resolving disputes) and peacebuilding (i.e. broad post-conflict agenda to secure peace) tend to mix peace with development and security as the latter are not provided by States that are too weak for it. The notion of “human security” captures this tendency. It was developed in the 1994 UN Human Development Report as a people-centred and multidisciplinary understanding of security that focusses on providing “freedom from want” and “freedom from fear” (Hanlon and Christie, 2016). Therefore, according to Brendan McAllister, if the objective of international peace operations is security, then several essential factors contributing to peace are not reckoned with. He argues that currently peacemaking results in agreements that focus too much on structures and technicalities and not enough on relationships, inclusivity and overcoming deep enmities.

***

Peace is not only less likely to be achieved in the “Global South” but also more difficult to preserve in the West. In fact, non-Western State actors, mainly Russia, China, Turkey and Iran, have embraced “weakness politics” to challenge the global balance of power while still remaining under the threshold of war.

To undermine peace in Western societies in a non-frontal manner, non-Western States resort to hybrid modes of actions that are “multidimensional, combining coercive and subversive measures, using both conventional and unconventional tools and tactics” (EEAS, 2018). For instance, Russia conducted disinformation campaigns during the 2016 US presidential elections, the 2016 Brexit referendum and the 2019 EU parliamentary elections. It sought to polarise and destabilise Western societies, thus threatening their domestic peace i.e. their harmony and ability to resolve contentious interests in an orderly manner. European societies’ solidarity and internal cohesion have also been threatened by Turkey and Belorussia’s weaponisation of migration waves. It is indeed an issue that divides EU member States and that has been appropriated and instrumentalised by European populist parties that spread anti-elite discourses and foster distrust between people and their representatives.

Non-Western States also attack Western societies in a more aggressive way, though always with hybrid actions difficult to detect and attribute according to the logic “weakness politics”. For instance, China regularly carries out cyberattacks on Western State agencies and companies like in 2009 with Operation Aurora that targeted US tech and security firms. In order to challenge the global balance of power, Iran resorts to proxies so as not to be held responsible for their anti-Western actions. It notably supports the Hamas in Palestine, the Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen, the latter of whom targeted US ships in the Red Sea in January 2024 in the context of the war in Gaza.

As a matter of fact, Western societies are highly vulnerable to hybrid threats created by non-Western States because they either don’t have the technical, human and legal resources to counter them or are not ready to compromise on their core values such as reducing freedom of speech to better thwart disinformation campaigns.

Peace turns out to be fragile and under jeopardy in the West. That’s why, in his 2021 Strategic Vision, the French chief of staff General Thierry Burkhard suggested to replace the peace-crisis-war continuum with a competition-dispute-confrontation continuum to better reflect the idealistic nature of peace. In fact, even though it is a figure of speech improperly using the term “war” as defined in introduction, according to General Burkhard competition amounts to “war before the war” while dispute is “war just before the war”. He thus underlines the absence of international harmony and the fragility of the current balance of power supposedly dominated by the West.

Conclusion

We have now come to the conclusion that indeed the world seems to be in a “no war, no peace” era because, in trying, and succeeding to a certain extent, to make a world free from wars, the West has actually caused the generalisation of an alternative form of warfare and globally weakened peace prospects. In fact, in the wake of the Cold war, the West established a world order with a strong power inequality to its advantage, which, along with democratisation, economic globalisation and nuclear weapons, has prevented the outbreak of inter-State wars between major global powers. However, this power inequality whose objective was to ensure peace was actually felt as a humiliation in the non-Western world. The latter’s frustration has then translated into the adoption of “weakness politics” as a way to challenge the world order without risking confronting its defenders frontally. It caused the development of “small” unconventional wars that take place out of the Westphalian framework and that have complexified peacemaking. The adoption of “weakness politics” as a mode of resistance against Western domination also resulted in non-Western States creating hybrid threats to undermine Western societies’ peace i.e. their harmony and ability to orderly resolve internal contentious interests.

1 Comment

RUSSIA-CHINA: friends to enemies? – geopol-trotters · 17 May 2025 at 3:51 pm

[…] In the early 2010s, Vladimir Putin’s Russia initiated a “Pivot towards the East”, in particular towards China. This strategic shift from Europe to Asia became a central aspect of Russia’s foreign policy following the invasion of Crimea in 2014 and its 2015 intervention on Bashar al-Assad’s side in Syria. Indeed, Russia fell under Western sanctions and found itself more and more isolated on the global stage. That’s the moment when it sought to consolidate its participation in the BRICS and deepen its relation with China, as it was looking for partners sharing the same rejection of the Western-dominated world order. […]