CHINA in AFRICA, a “shared future”?

What you want to understand: 🤔

- What economic and diplomatic benefits does China get from being in Africa?

- Is China as dependent on Africa as Africa is on China?

- Does China actually contribute to the development of the continent?

- Does China consider Africa as an equal partner or solely as a source of resources and a client?

- What is the Belt and Road Initiative and how is Africa a major part of it?

- What are the characteristics of Chinese loans that accompany infrastructure projects for African countries?

- Can we speak of “debt-trap diplomacy”?

- What narrative has China developed to spread its soft-power?

- How important is the Chinese military presence in Africa and how will it evolve?

- What challenges will China have to face in order to maintain and reinforce its influence on the continent?

Before reading this article, I advise you to take a look at China and the World since 1949 in order to better grasp China’s evolution until now and understand its approach of international relations.

During the 1990s, China accumulated loads of foreign currency reserves, in particular in US dollars (USD) by buying US government debt. Following the 2008 subprime crisis, assets in USD yielded low returns. Therefore, China sought to boost investments overseas to diversify its assets.

As a matter of fact, the Chinese government had already launched the “Go Out Policy” in 1999 to incentivise its companies to undertake business projects abroad. However, the 2008 crisis was a sort of wake-up call for China that started investing massively in Africa.

China’s move towards Africa was facilitated by manipulations of its currency’s exchange rate to keep it low and thus foster exports. This is a completely different subject but for those of you who might be interested in explanations about China’s macroeconomic strategy, please find below some remarks. For the others, you can skip the next part and go directly to I. Why is China in Africa ?

China’s currency, the renminbi, had a sort of fixed exchange rate and was pegged on the USD. If it had had a floating exchange rate, dependent on market forces, it would have had appreciated a lot against the USD for years. However, China managed to counter-balance market forces to maintain its exchange rate low by buying USD and selling renminbi.

In fact, China had a high saving rate compared to its levels of domestic consumption and investment. It was due to borrowing constraints (inefficient state-owned banking system), a culture that induced to save to provide for the elderly, and tight capital control that prevented foreign capital inflows. Because Net Exports = Savings – Investments, then China had surpluses that it had to export. It bought huge quantities of US government bonds, which decreased US interest rates (because large supply of funds), appreciated the USD and relatively depreciated the renminbi. As a consequence, Chinese exports were facilitated. It is again another subject but the US trade deficit worsened dramatically as a result.

I. Why is China in Africa ?

The 2 objectives of China in Africa are :

- Sustaining its economic activities and remaining the “World’s Factory”

- Gaining diplomatic support from countries that refuse Western hegemony

A. Remaining the “World’s Factory”

China has different approaches depending on the level of development and revenue of its partner:

- Intermediate revenues → South-Africa and Egypt

- Fostering the creation of capital-intensive industries

- Rich in resources → Ghana, Nigeria, Congo, DRC, Angola, Zambia, Algeria…

- Exploiting resources and providing infrastructure logistics linked to resource exploitation

- Least advanced and without much resources → Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania…

- Not much investment even though the goal is officially to contribute to the industrialisation and modernisation of these partners

The reasons for China’s massive inflows of money in Africa are the following (source):

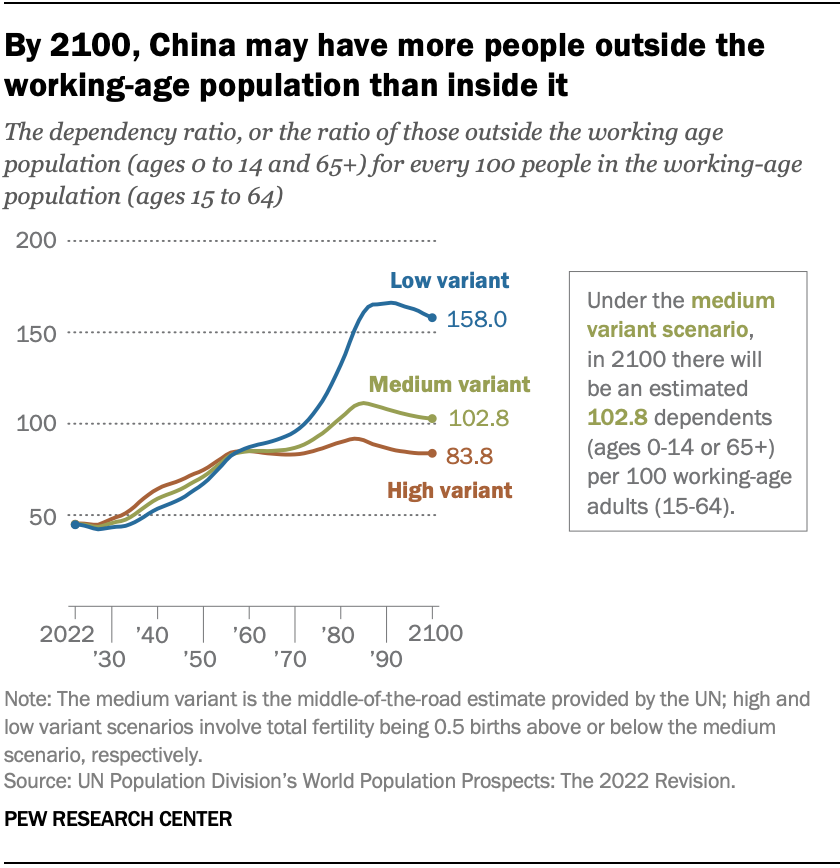

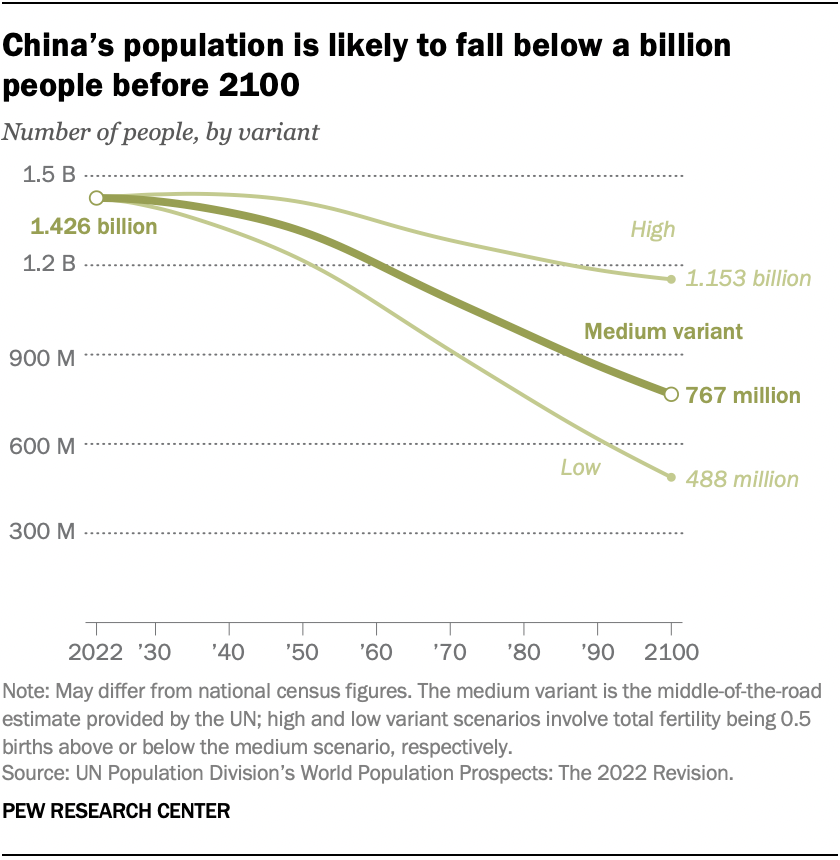

1. China no longer has the workforce to sustain its economic activities

The Chinese population is not only ageing but is also declining quite rapidly: by 2050 half of it will be older than 51 and by 2060 one third will be older than 65. Moreover, the population will fall below 1 billion by 2080.

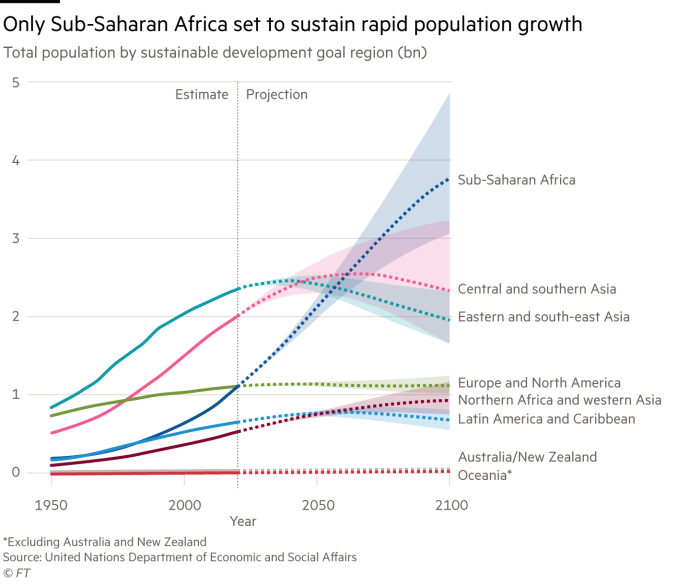

As a consequence, China is desperately looking for workers for its labour-intensive manufacturing activities. It has found them in Africa, the continent with the most dynamic demographics. Indeed, by the end of our century, its population will have increased fourfold.

2. China’s labour cost is dramatically increasing

Value chain: series of consecutive steps that go into the creation of a finished product, from its initial design to its arrival at a customer’s door. It includes steps like sourcing, manufacturing, marketing, after-sales service (source: Investopedia).

Given the evolution of China’s labour cost, the country is trying to reposition itself up in the value chain. China has more and more difficulties contributing to lower levels of the value chain and therefore looks for cheaper places of production so as to sustain its level of Made in China exports and remain the “World’s Factory”. That’s why some Chinese industries have delocalised parts of their activities to South-East Asia and Africa where wages are much lower.

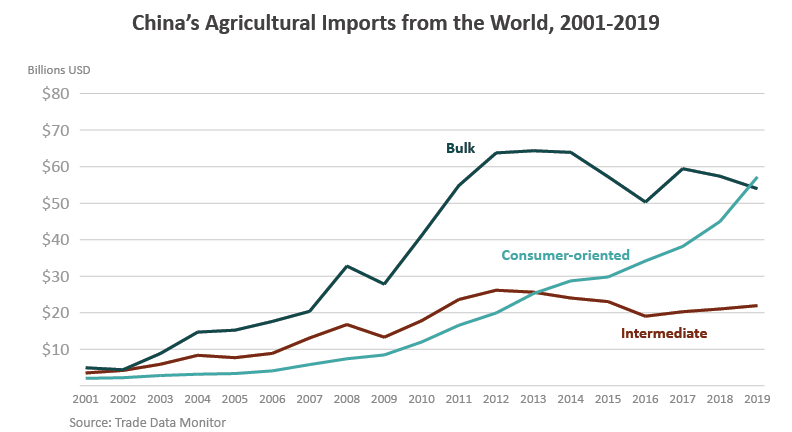

3. China is the world’s largest agricultural importer

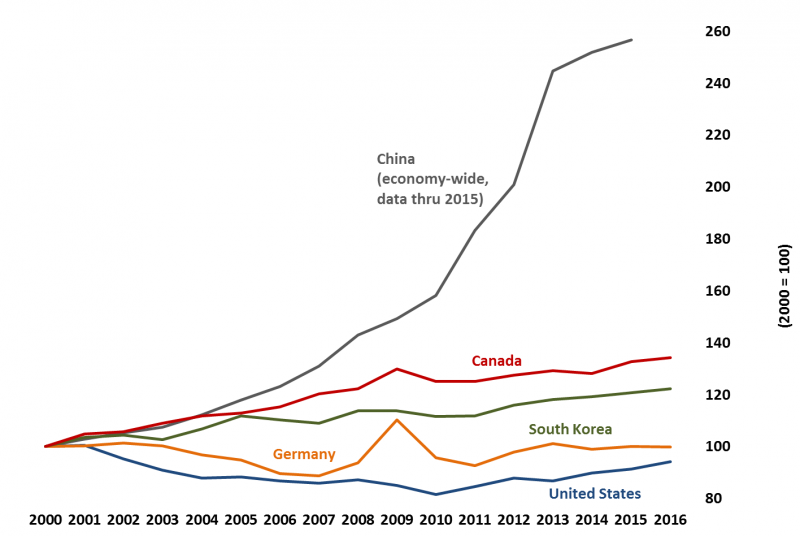

Due to urbanisation, rural exodus and a growing middle-class with new diet patterns, China is a net importer of agricultural products since 2004. As a matter of fact, China’s food self-sufficiency index is decreasing year after year.

“Intermediate”: commodities that will be processed in China to be sold

“Consumer-oriented”: meant for direct consumption

Source: US Department of Agriculture

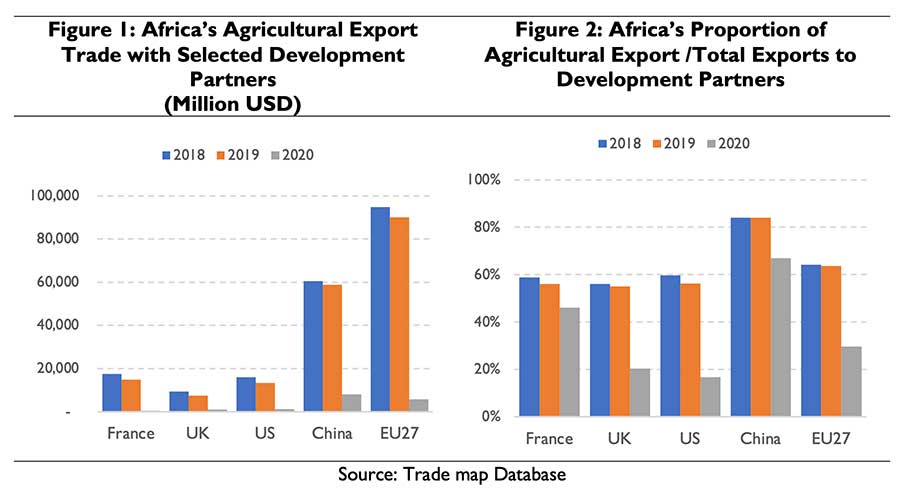

Africa can supply China’s growing domestic demand for agricultural products. As you see on Figure 1, China is the first destination for African agricultural export. Figure 2 indicates that more than 80% of Africa’s exports to China were agricultural products before the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. China needs raw materials and energy

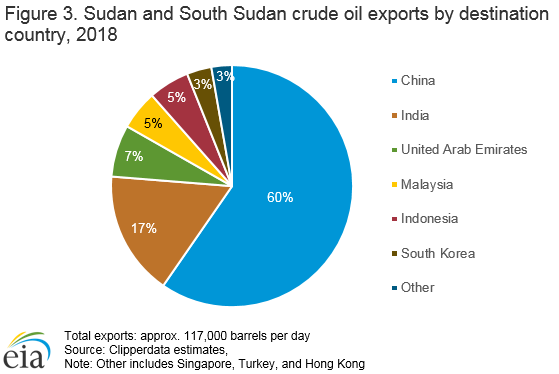

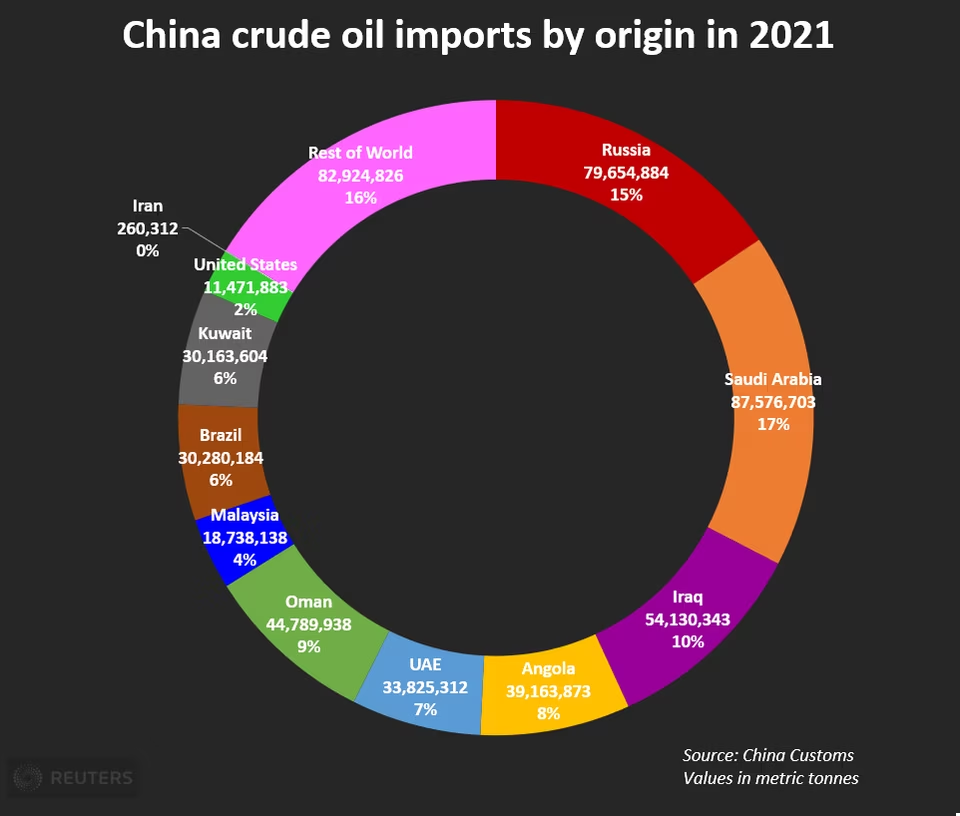

China needs long-term energy supplies to sustain the pace of its industrialisation. Africa exports 25% of its oil and gas to China, making it its second largest supplier after the Middle East. Therefore, it is unsurprising to see figures like 72% of Angola’s oil exports going to China in 2021 or those on the following chart.

As you’ll see further down this article, China doesn’t depend that much on Africa for its supply of energy. Dealing with African countries for these commodities is a way to diversify its supply sources and not depend too much on only few actors.

5. Africa is a fast-growing consumer market

Chinese companies see obvious business opportunities in Africa when presented with the following similarity: the African middle class amounts to around 350 million people, it is around 400 million people in China. Besides, the African urbanisation rate is surging as fast as China’s one some years ago. Currently, around 42% of sub-Saharan inhabitants live in cities whereas it is 63% for the Chinese.

Chinese companies expect China’s socio-economic model of development to replicate in Africa. They hope to conquer Africa’s emerging consumer market by supplying its growing demand for energy, consumption goods, health, entertainment, finance and so on.

Moreover, the Chinese domestic consumer market is saturated such that companies search for new outlets like Africa where their financial power allows them to gain substantial market shares.

6. Circumventing trade barriers on Chinese exports

In case of a trade war in which an international actor imposes restrictions on Chinese exports, as the US did under Donald Trump, China could circumvent these barriers by producing and exporting some of its products from Africa.

B. Reinforcing China’s weight on the international stage

China has much to gain by extending its sphere of influence to the 54 African countries. It especially seeks to reinforce its leverage at the UN to counter-balance Western powers and put into question the world order they have shaped for a while now.

China has already reaped some benefits from its activities in Africa. In 2020, 53 countries issued a statement supporting China’s crackdown in Hong Kong, half of them were Africans. The same year, at the UN, China obtained the leadership of 4 of the 15 UN specialised agencies: the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, the International Civil Aviation Organisation, the International Telecommunication Union and the UN Industrial Development Organisation.

China also tries to use the UN to exclude Taiwan from the international stage and eliminate all remaining recognition of its government. In Africa, the only country that still recognises Taiwan’s government is the Kingdom of Eswatini, a small country landlocked between South-Africa and Mozambique.

II. An unbalanced economic partnership

A. Interdependence ?

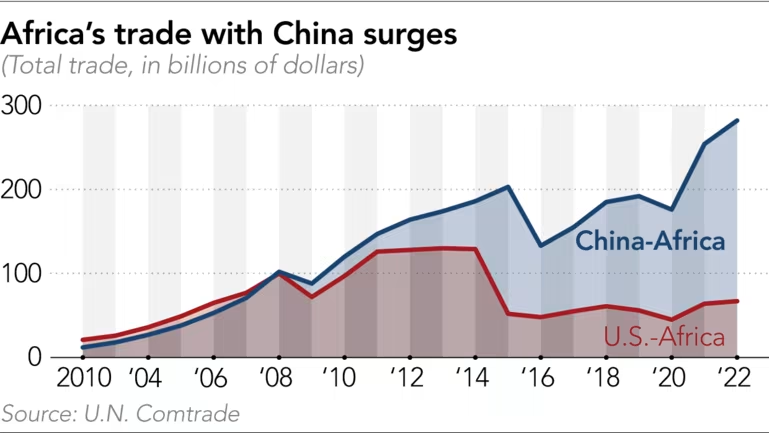

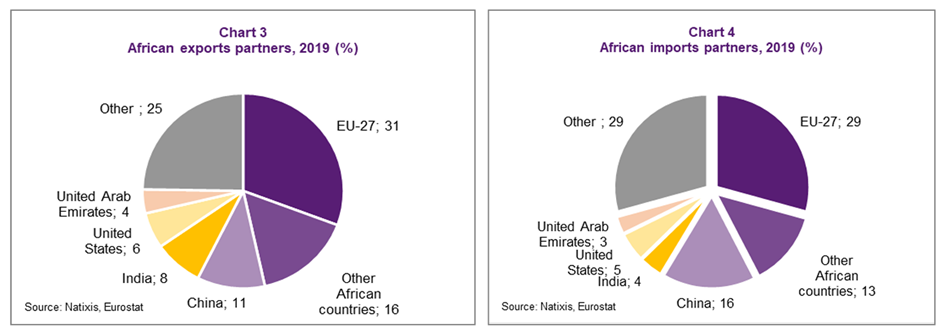

Over the past two decades, China has clearly taken over “traditional” foreign powers and consistently increased trade cooperation with its African partners.

However, we should bear in mind that while China is a major trade partner for Africa, Africa is definitely not that important for China.

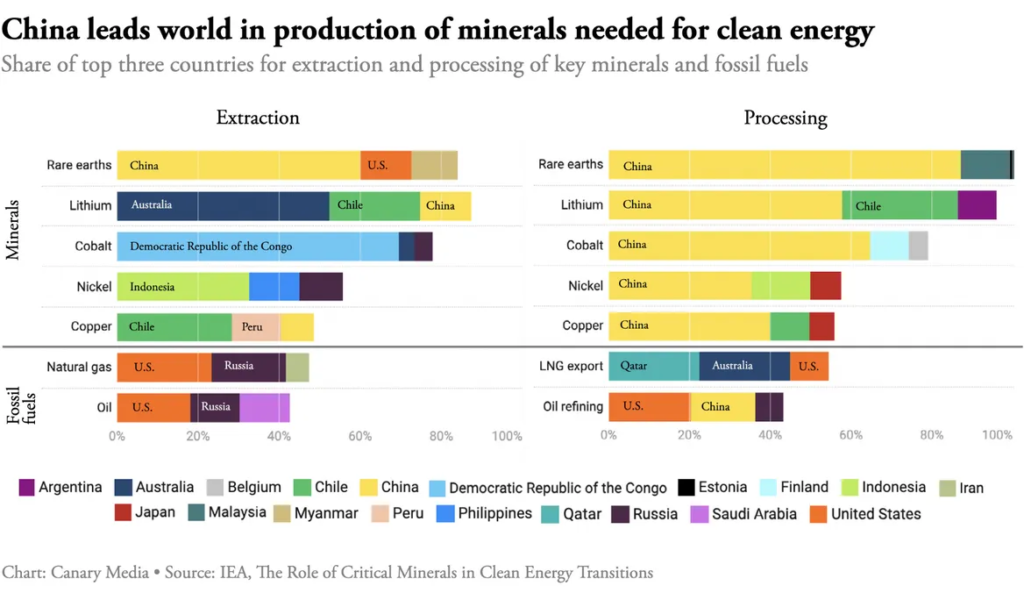

In fact, Africa only represents 3-4% of China’s global trade. Besides, the Asian giant has multiple alternatives for its supply of energy commodities. Likewise when it comes to minerals, China has plenty of alternatives as well and its soil even contains lots of them.

Nevertheless, Africa is strategic for China as it is located along maritime and terrestrial routes that lead to the European market i.e. China’s chief target. Furthermore, even though from a macro-economic perspective Africa doesn’t weigh much for China, from a micro-economic point of view Chinese companies have a lot of business opportunities to exploit in Africa.

As you can see with the following charts, Africa actually relies heavily on China for its trade. For example, as we mentioned earlier, Africa exports 25% of its oil and gas to China. Therefore, shifts in China’s demand can have a substantial impact on Africa’s economic stability.

B. China sets up its own business operations but doesn’t actively develop the continent

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): situation in which an investor, company or country acquires for the long-term a substantial stake in a business or project located abroad. It can also buy it outright to expand operations to a new region.

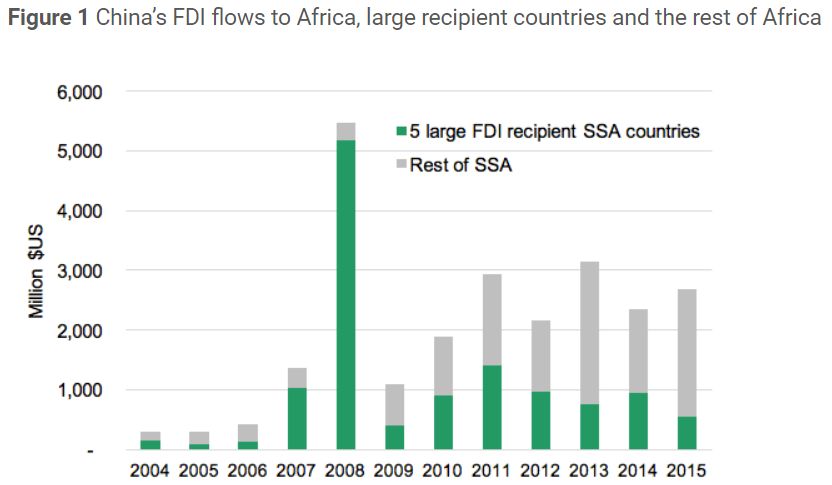

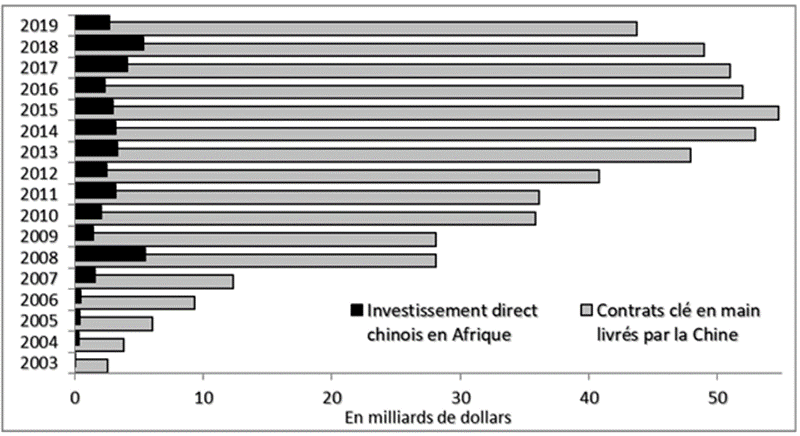

As you can see on the graph above, China’s presence in Africa is not that much about investing to acquire local assets and develop local activities (FDIs). It is much more about exploiting local resources and selling its merchandises and services (e.g. building roads, dams, telecommunication networks…).

I invite you to read again this paragraph. It is core to understanding Chinese approach in Africa.

In 2019, Chinese companies’ turnover in Africa was almost 15 times higher than the value of Chinese investments in the continent. Until recently, Chinese FDIs to Africa were quite limited: in 2019, only 2% of China’s FDIs went to Africa whereas the global average was 2.4%.

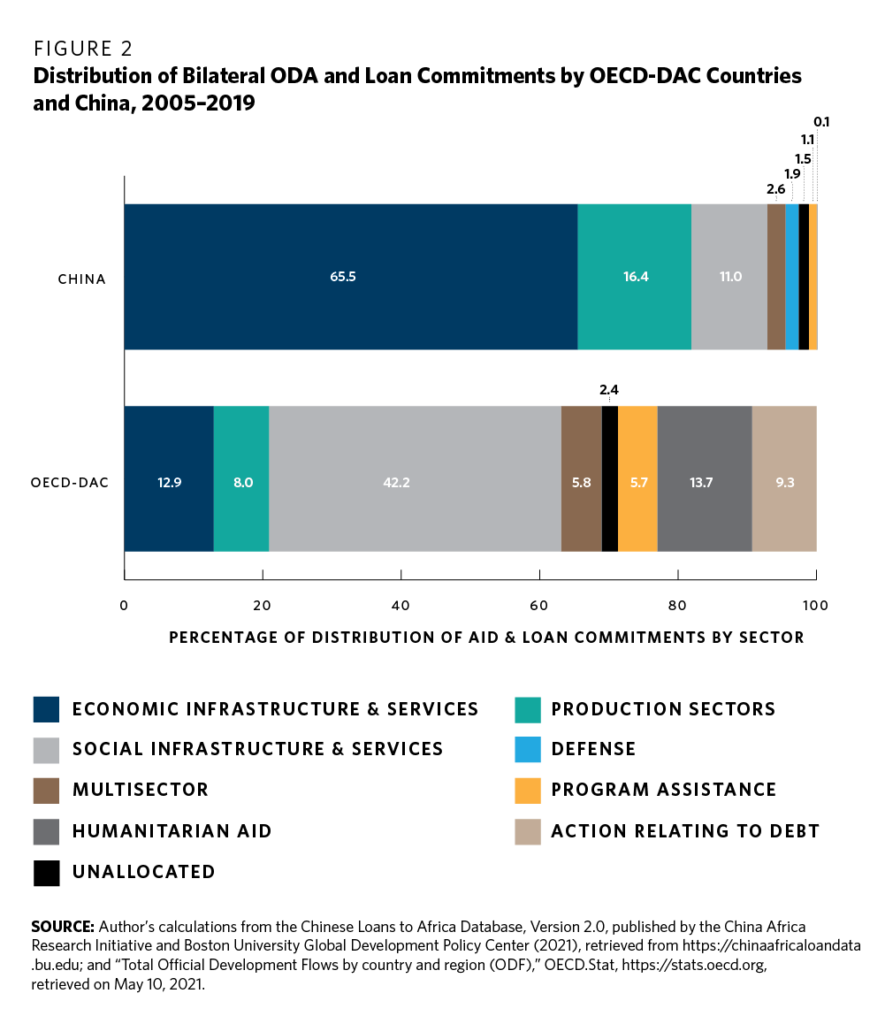

Looking at where China puts its money is also quite revealing of China’s willingness to do business in Africa without necessarily engaging in the long-term development of the continent.

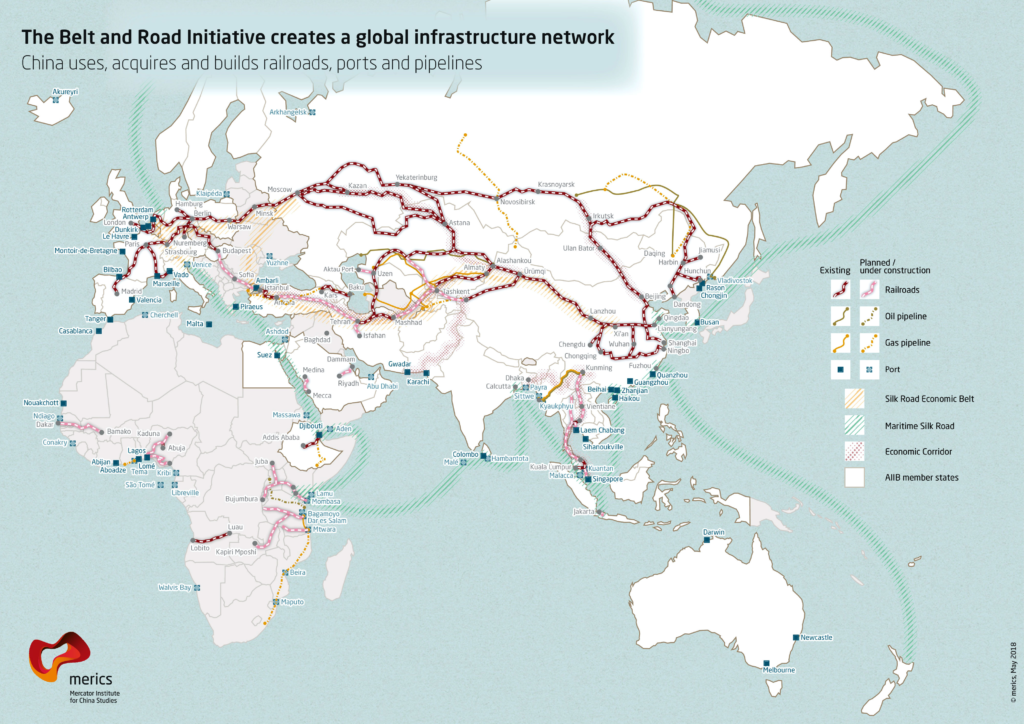

China gets involved in transport, energy and mining sectors, especially in Eastern and Central Africa as these regions will be integrated into the Belt and Road Initiative that needs infrastructure.

Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): strategic project launched in 2013 by Xi Jinping with the objective to connect China to the European market through land, rail and naval routes. This project requires infrastructure and so far 149 countries, including 49 African countries, have joined the BRI by signing construction, trade and other kinds of cooperation agreements with China. It is also definitely a way for the Asian giant to extend its political and economic influence overseas. Great map here with details → Mercator Institute for China Studies.

In fact, China builds roads, ports, dams, communication networks and various kinds of infrastructure in Africa. For example, 6,000 km of the railways that the continent possesses have been laid by China (2022 figure). Through the China International Water & Electric Corporation, China has built the Merowe Dam in Sudan in 2009 for roughly $2 billion. Likewise, the China Road and Bridge Corporation built the Maputo-Katembe bridge in Mozambique in 2018 for $726 million.

The establishment of Chinese companies in Africa sometimes lead to the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZ).

Special Economic Zones: area with different business and trade laws from the rest of the country. Usually, companies that set up their factories and buildings in these zones benefit from attractive governmental measures such as tax incentives and lower tariffs.

Here’s a list of China-Africa SEZ with the share of Chinese companies operating in them (source):

- Jiangling (Algeria) → 100% of Chinese companies

- Eastern (Ethiopia) → 100%

- JinFei (Mauritius) → 100%

- Chambizi (Zambia) → 95%

- Ogun (Nigeria) → 82%

- Suez (Egypt) → 75%

- Lekki (Nigeria) → 60%

Depending on the source, there are between 3,000 and 10,000 Chinese companies in Africa. Some of them are actually African companies registered locally but managed by Chinese nationals. There are actually different kinds of Chinese companies operating in Africa:

- Those that conduct business at the behest of the Chinese government, in particular in the mining industry to send back natural resources to China

- Those that pursue private interests and compete for markets to make profits

- Those, often small, that try to establish themselves in Africa but whose fate depends greatly on Beijing’s support

C. Chinese loans go hand in hand with infrastructure projects

Before reading this part, I believe it is worth reminding few key definitions:

Equity: value of a company minus all its liabilities (debts). It can also be described as the amount of money that the company’s owner has invested or owns.

Maturity: date at which an investment ends. From the perspective of a borrower who has contracted a loan, this is the date at which he will have to have reimbursed the entirety of his debt to the lender.

Debt restructuring: renegotiating the terms and conditions of an existing loan to avoid the risk of defaulting. Most of the time, China can reschedule its loans but rarely changes the interest rate or the principal.

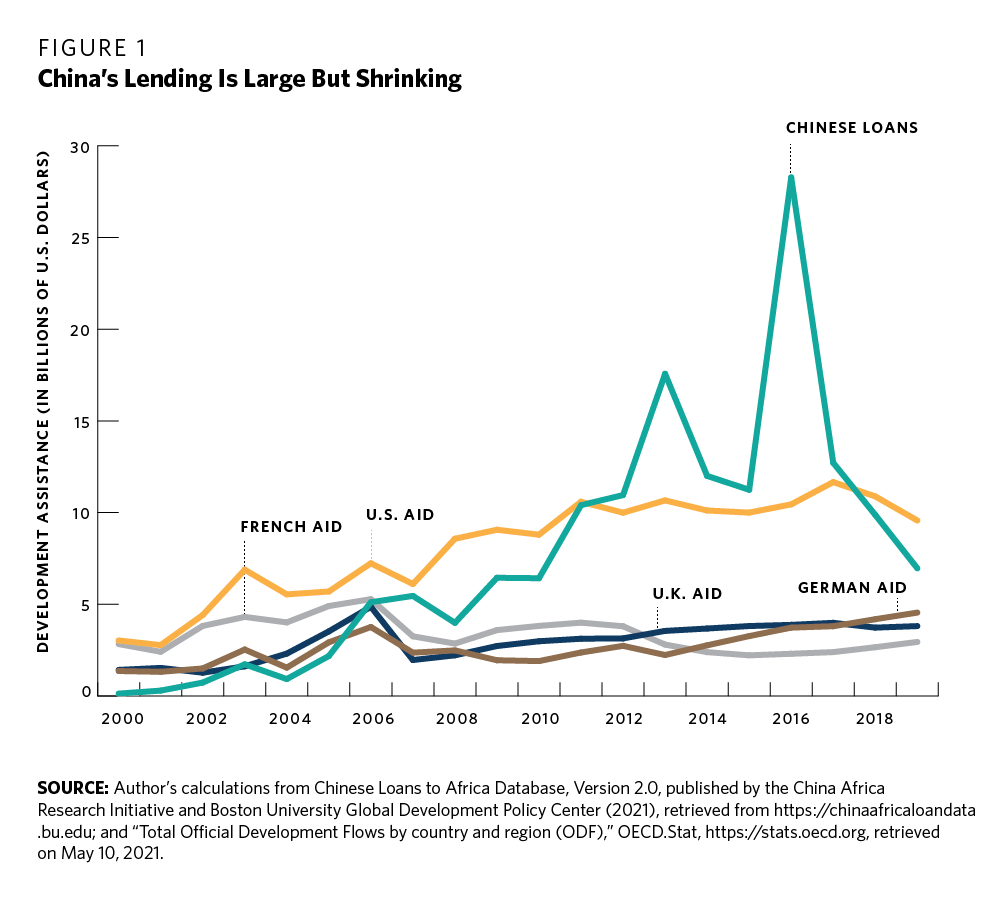

As a matter of fact, most of the money invested by China in Africa goes to construction projects under the form of loans. China is by far the most important lender for infrastructure projects on the continent. It is worth noting that between 2000 and 2019, 7 countries concentrated 2/3 of Chinese loans in Africa: Angola, Ethiopia, Zambia, Kenya, Nigeria, Cameroon and Sudan.

Most of the loans come from:

- 3 policy banks (their equity belongs to the Chinese government and their loans’ interest rates are often below those of the market or their maturity is much longer)

- Export-Import Bank of China (EXIM)

- China Development Bank (CDB)

- Agricultural Development Bank of China (ADBC)

- 4 commercial banks (with their own agenda but also serving the interests of the Chinese regime)

- China Construction Bank

- Bank of China

- Agricultural Bank of China

- Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC)

China also intervenes financially in Africa through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, the African Development Bank Group or the Eastern and Southern Africa Trade and Development Bank.

Below you’ll find some common characteristics of Chinese loans to African countries.

1. Resource-financed infrastructure projects

China proposes loans that will be repaid with future export revenues of local natural resources. For example, in 2017, Guinea signed an agreement with the ICBC and the EXIM for $587 million according to which the loan it has contracted for two road construction projects will be repaid with revenues from bauxite exploitation and export.

There are only very few instances of Chinese resource-for-infrastructure projects. These projects imply that Chinese companies build infrastructures in exchange for concessions to exploit local resources.

2. Creating a specific bank account for reimbursements

The debtor has to create a specific bank account outside of his country where he deposits all the revenues generated by the project in order to repay the loan. The money deposited then directly falls in the hand of the Chinese lender.

3. Priority given to Chinese operators

African authorities have to consent to let Chinese companies handle the project. As you’ll understand while reading this article, China doesn’t contribute to developing local economies as it deprives local companies of business opportunities by giving them to its own companies. It seeks to exploit local natural resources the way it wants. For example, in Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon, Chinese companies cut trees 24/7 and don’t respect the basic rule of leaving 25 to 30 years for a parcel to regenerate. They also put lots of pressure on subcontractors and don’t consult local civil organisations to discuss the impact of their activities on the population and the environment. The systematic corruption of civil servants also helps carrying on with these illegal practices.

Despite giving priority to Chinese inputs for projects in Africa, Chinese companies most of the time have no other choice but to hire local employees as it is more convenient and cheaper than having Chinese workers. Nevertheless, there have been reports of exploitation and bad treatment of local employees (source: HRW). That’s why, in 2012, Zambian miners killed a Chinese manager during a pay protest.

4. The lender has the discretion to end the contract when it deems necessary

Loans proposed by Chinese lenders often include a provision according to which the lender can end the contract and claim immediate full repayment if the borrower defaults on its other lenders.

In many contracts of the China Development Bank, there is also the possibility to break all diplomatic relations in case of default by the borrower.

5. “No Paris Club”

Paris Club: informal group of creditor nations whose objective is to find workable solutions to payment problems faced by debtor nations. It is made up of 22 Western countries (Investopedia).

China specifically asks that when an African country wants to restructure its debt, it doesn’t coordinate with Paris Club members or get them involved in any way. It wants to be the only one to manage the restructuring of its loans.

6. Seizure of an asset in case of default? No.

The idea that China could seize the asset in case of default seems to be a myth… So far, China has never seized any asset in Africa. Many use the example of the Sri Lankan port of Hambantota that was “handed over to China” in 2017 for a 99-year lease. But it was actually not a debt-equity swap! Some research on the Internet and you can easily see that this example has been distorted and manipulated to fuel the “debt trap diplomacy” narrative against China (The Atlantic, Georgetown University, The South China Morning Post, The Diplomat…).

China doesn’t seek to seize assets but insists on being repaid in full for all its loans. It is not the kind of partner to make concessions and gifts (other than calculated ones that are part of bigger schemes).

China’s all-round offers (financing-construction-exploitation) seduce African leaders. In fact, some leaders may want quick results for short-term political objectives and China is able to deliver these results.

Nevertheless, the volume of Chinese loans has significantly declined since 2016. It is probably due to concerns about African countries increasingly apparent inability to repay. China is more cautious now and wants to secure its reimbursements. That’s why it has stopped and downscaled some of its projects like the Standard Gauge Railway between the two Kenyan cities of Mombasa and Nairobi that was initially supposed to extend to the Ugandan border.

D. Can we speak of “debt-trap diplomacy”?

Debt-trap: situation in which a borrower is forced to take new debts simply to repay existing ones. The debt burden usually goes beyond control in a vicious circle and the borrower eventually defaults.

Debt-trap diplomacy: situation in which the lender uses a debt-trap to gain political leverage over the borrower.

To the question whether China conducts a debt-trap diplomacy in Africa, the answer is far from being obvious.

There is definitely not enough evidence to assert that China promotes inappropriate loans that are inherently unsustainable for their borrowers. Even though Chinese loans’ terms and conditions are often very strict and demanding, it seems too easy to point fingers at China whenever an African country has a high risk of debt distress. In fact, African countries borrow from multiple countries and organisations, not only from China. Often times, they are themselves responsible for the poor management of their debts.

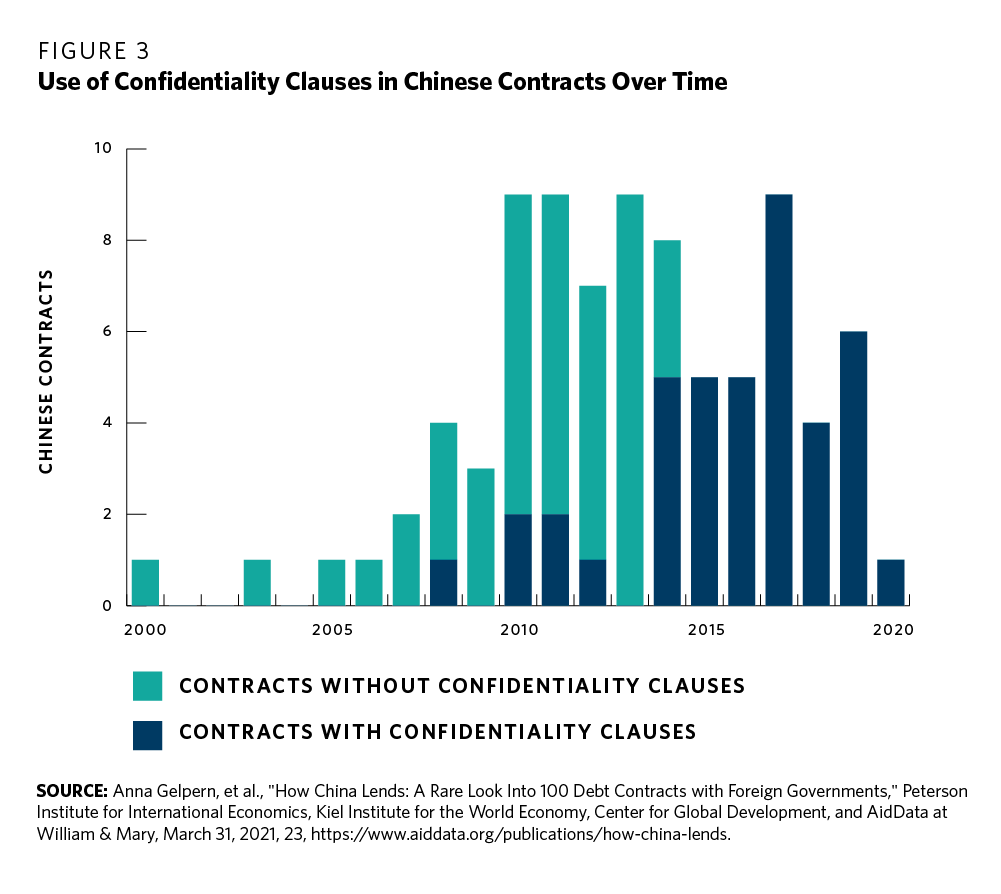

All the suspicions around China’s lending in Africa actually comes from the fact that it doesn’t produce any reports on how and where its money goes. As a matter of fact, according to Horn et al (2019), China doesn’t officially declare around 50% of its loans to developing countries. Besides, many if not all Chinese loans have non-disclosure and confidentiality clauses.

Many projects of the Belt and Road Initiative are uncoordinated and unplanned and several Chinese lenders compete to offer credit to African partners. Consequently, seeing China’s lending strategy in Africa as monolithic can be misleading.

In September 2022, amid accusations of debt-trap diplomacy, China cancelled 23 zero-interest loans for 17 African countries. These loans were approaching maturity and represented only a tiny bit of China’s stock of debts in the continent. Also bear in mind that Chinese zero-interest loans in Africa are extremely rare and that it is not the first time that China cancels this kind of loans for African countries. Notwithstanding, China used this gesture as a way to portray itself as a “great and responsible power”.

III. China’s narrative and soft-power in Africa

China’s objective in Africa is to project an image different from the one described by Western media.

China likes to present itself as the biggest developing country in the world. Since Africa is made up of many developing countries, they should cooperate to fight the remnants of Western hegemony together.

Furthermore, China wants to appear as a success-story country that has managed to achieve economic prosperity. African rulers admire its model of development based on authoritarianism and economic reforms.

So as to take full advantage of this image and reinforce it, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) funded the construction of the Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School in Tanzania. As you may have already guessed, it’s a Chinese company that built the school between 2008 and 2022. Political movements that fought for independence in South-Africa, Mozambique, Namibia, Angola, Zimbabwe and Tanzania have participated in the establishment of the school.

Courses offered at the school focus on pan-Africanism and the CCP uses them to promote China’s stance in Africa and influence young generations of African leaders.

The communiqué of the Chinese embassy in Tanzania on the occasion of the inauguration ceremony of the school in February 2022 provides us with a perfect example of China’s narrative with regards to its relation with Africa:

- “strengthen the exchange of state governance experience with parties in Africa”

- China wants to reinforce its connections with African political spheres to facilitate its business activities and enjoy wider diplomatic support on the international stage.

- “support each other in pursuing development paths that suit their own national conditions“

- China will not impose its model on African countries and will seek to participate in their development, as long as it means more business deals.

- “deepen pragmatic cooperation across the board”

- When China focusses on business, it solely focusses on business. It doesn’t look at the country’s politics or respect of human rights for example. African countries have had enough of being patronised. China has well understood it and avoids moralising discourses.

- It is seducing for African countries in comparison with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that conditions its loans to liberal political and economic reforms. That’s why Sudan kept on receiving loans and grants from China while it was under international sanctions as of the 1990s.

- “promote the building of a high-level community with a shared future between China and Africa”

- China tries to create long-term bonds with the continent by targeting its future leaders.

In the same perspective as with the Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School, there are 61 Confucius Institutes in 46 African countries that teach Mandarin and spread Chinese culture. The first one was built in Nairobi, Kenya, in 2005.

Likewise, since the 1950s, China has welcomed African students/militants in its universities to spread its ideology and extend its network of supporters overseas. It was the case for Algerians from the National Liberation Front (FLN) and for South Africans from the African National Congress (ANC). China keeps on incentivising African students to come to China by offering scholarships.

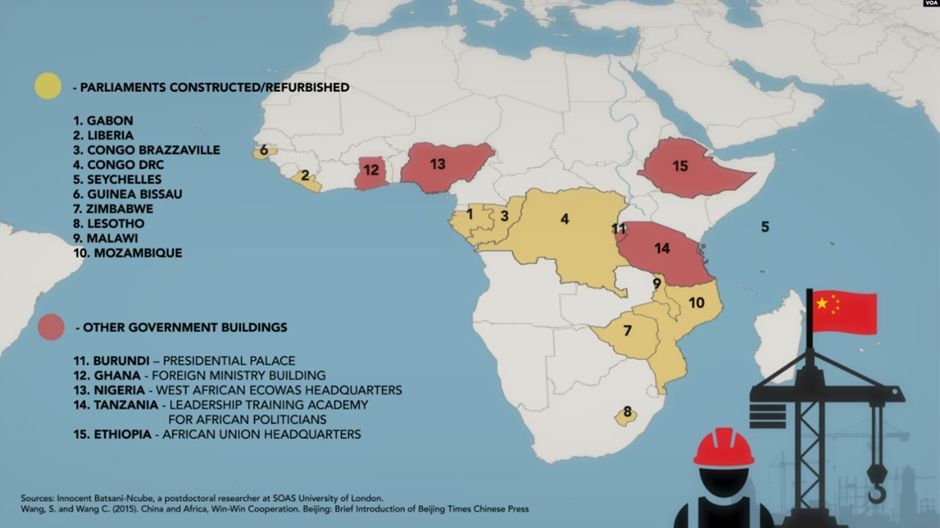

For reputational purposes, China builds new African parliaments and institutional buildings as gestures of goodwill. However, in 2018, there was a controversy over the alleged bugging of the African Union headquarters that China had built few years earlier in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Chinese influence in Africa extends to various spheres of the society and obviously to the media. In 2018, a South-African journalist had his column taken away after he published an article critical of China’s treatment of the Uyghurs. In fact, a Chinese company held a 20% stake in the publishing society named “Independent Media”… The Chinese digital TV operator StarTimes endeavours to give all Africans access to satellite television and so far 27 million of them use its services. However, this implies that StarTimes can have control over what Africans see and don’t see on TV. Another quite influential Chinese company is Huawei that is currently working on the development of a 4G Internet network in various African countries like Uganda.

Even though Chinese projects’ primary objective is not Africa’s long-term development, they seduce Africans as they create better prospects. Local inhabitants get access to telecommunication services, can drive on proper roads, travel the country thanks to railways (if they can afford it) and take advantage of infrastructures for their businesses. It is quite paradoxical because China is accused at the same time by local authorities (when not corrupted) of exploiting natural resources while not building up local economies and even damaging the environment. As we saw, Chinese companies prioritise Chinese inputs and hire local workers only for non-skilled physical labour, in mines for example.

It is thus quite hypocritical of China to speak about a “shared future” and “mutual benefits”. China first and foremost seeks to do business in Africa with little regard for the social and environmental consequences of its activities.

IV. Military cooperation

China’s military presence on the continent boils down to its Djibouti base that was constructed in 2017. It is the only Chinese overseas military base in the world. Its role is to monitor naval traffic in the Red Sea and enable potential force projections in the Horn of Africa.

However, according to The Economist, US intelligence believes that China wants to implement new military bases like in Equatorial Guinea. Many commentators say that it is only a question of time before China expands its military presence in Africa.

Regarding arm trade, between 2010 and 2021, China accounted for 22% of arm exports to Sub-Saharan Africa, Russia being by far the largest exporter. At first China sold small-size weapons but it is now providing heavier ones like drones, for which African countries have much interest. For instance, the Democratic Republic of Congo purchased 9 CH-4 drones to China in February 2023 in order to fight the M23 rebellion. According to some reports, the DRC would also be interested in Chinese fighter jets… Overall, Chinese weapons are known for being cheap as well as for the absence of questions from the Chinese government regarding their eventual use.

China also provides training to African troops and regularly conducts joint military exercises. It is particularly the case with Tanzania and South-Africa. Indeed, South-Africa conducted joint naval exercises with China and Russia off its shores in 2019 and in early 2023.

Nevertheless, we should not overstate China’s military involvement and influence in Africa. It doesn’t compare with the strength of the bonds that Russia and Western powers have created over the years with Africa. We should also not forget that China’s main security focus is South-East Asia and more specifically Taiwan.

In the field of law enforcement, China also participates in joint trainings and operations with its local partners. As a matter of fact, some African rulers want to adopt China’s model of law enforcement. It is worth noting that in order to preserve its image on the continent, particularly vis-à-vis the youth that may be more prone to demonstrate, China wants this kind of cooperation to stay under the radar.

V. Limits and challenges to the Chinese presence in Africa

China will have to reckon with the fact that African countries’ debts are surging. Therefore, they won’t be able to finance infrastructure projects with debt anymore. They will have to think about something else and so will China if it wants to remain a first-choice partner.

Besides, African governments may be tempted to prioritise repaying their debts instead of spending money in key development sectors like education or health. This could spark social unrest, which can be directed either towards governments or towards their foreign lenders.

Moreover, China’s low level of FDIs can lead Africans to blame it for exploiting their resources without contributing to their country’s development and ultimately to the improvement of their living conditions.

In fact, African state authorities start demanding more investments in local African enterprises while China privileges its own companies for its business operations there. This is captured in the statement of Amadou Hott, Senegalese minister of Economy, during the 2021 China-Africa Forum in Dakar: “We have a lot of investments in debt, we need more investments in equity”. China has a problem here because on one hand it is looking for bankable projects, like constructing ports or developing telecommunication networks, and on the other hand Africans need water treatment plants and roads in poor rural areas (not bankable…).

Furthermore, African governments can start objecting to the conditions of Chinese loans like President Tshisékédi of the Democratic Republic of Congo who in May 2023 travelled to China so as to renegotiate mining contracts and find better conditions for his country.

Additionally, Africans want transparent and trustworthy leaders, something for which the Chinese model is not reputed. It is also no wonder why the opacity of contracts that are kept away from the public eye fuels rumours and casts doubts on the reality of Chinese intentions.

Another challenge that China will have to face is the security of the routes of the Belt and Road Initiative. Many African countries that this project concerns are plagued by political instability and conflicts. China will probably not stand idle by and will have to get involved into African countries’ governance and maybe participate in the diplomatic resolution of local conflicts as it tried to do during the 2013-2018 South-Sudan civil war. Will it be comfortable doing it ? Maybe not but what other choice does it have ? It already does it more and more in the Middle East like between Saudi Arabia and Iran in March 2023.

1 Comment

RUSSIA, a predator in AFRICA – geopol-trotters · 11 September 2023 at 7:25 am

[…] its goal in Africa, Russia competes with other global powers such as France, the US, the EU, China, Turkey… All of them approach this rivalry as a zero-sum […]