Daesh’s Statehood and Caliphate

What you want to understand… 🤔

- How did the Islamic State gain power in Syria and Iraq ?

- What is a Caliphate ? What is a State ? What are the advantages and drawbacks of claiming to be a Caliphate or a State ?

- What was the political, social and economic structure of the Islamic State at its peak in 2014-2015 ?

- What is Salafi-jihadism? What were the ideological foundations of the Islamic State’s project to dominate the world?

Before you start reading, I just want to inform you that this article is a research paper made during my undergraduate studies. Therefore the style is slightly different from what you’re used to reading on this blog. You’ll find my sources at the end of the article. Enjoy !

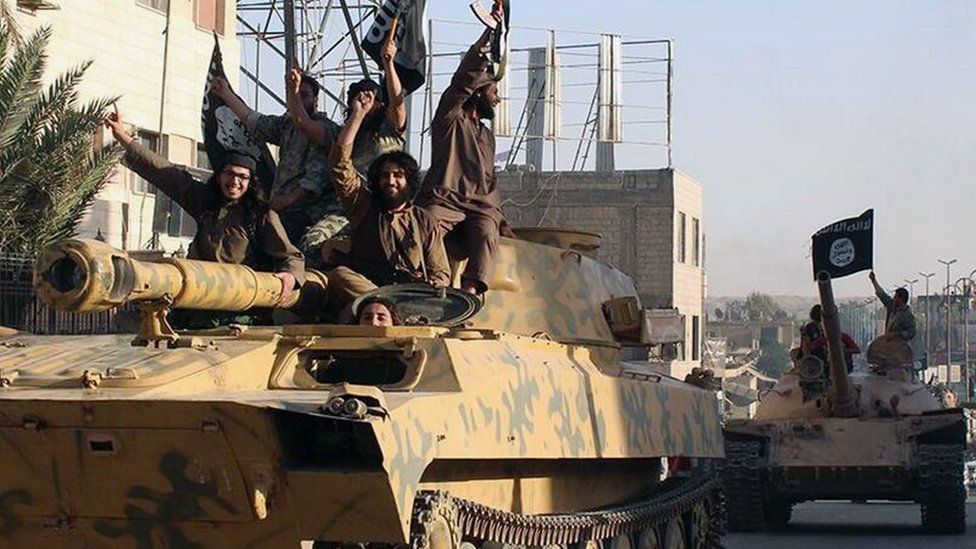

In the wake of the Syrian Arab Spring (2011), a terrorist organisation founded in 1999 by Abu Musad al-Zarqawi grew in power and conquered large swathes of territory in Syria and Iraq. The Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) eventually became the Islamic State (IS) when its spokesperson, Abu Muhammad al-‘Adnani, declared the establishment of a caliphate on June 29, 2014. From this date until September 2015, when it reached its all-time high in terms of territorial possessions in Iraq and Syria, IS experienced its highest level of influence in the region.

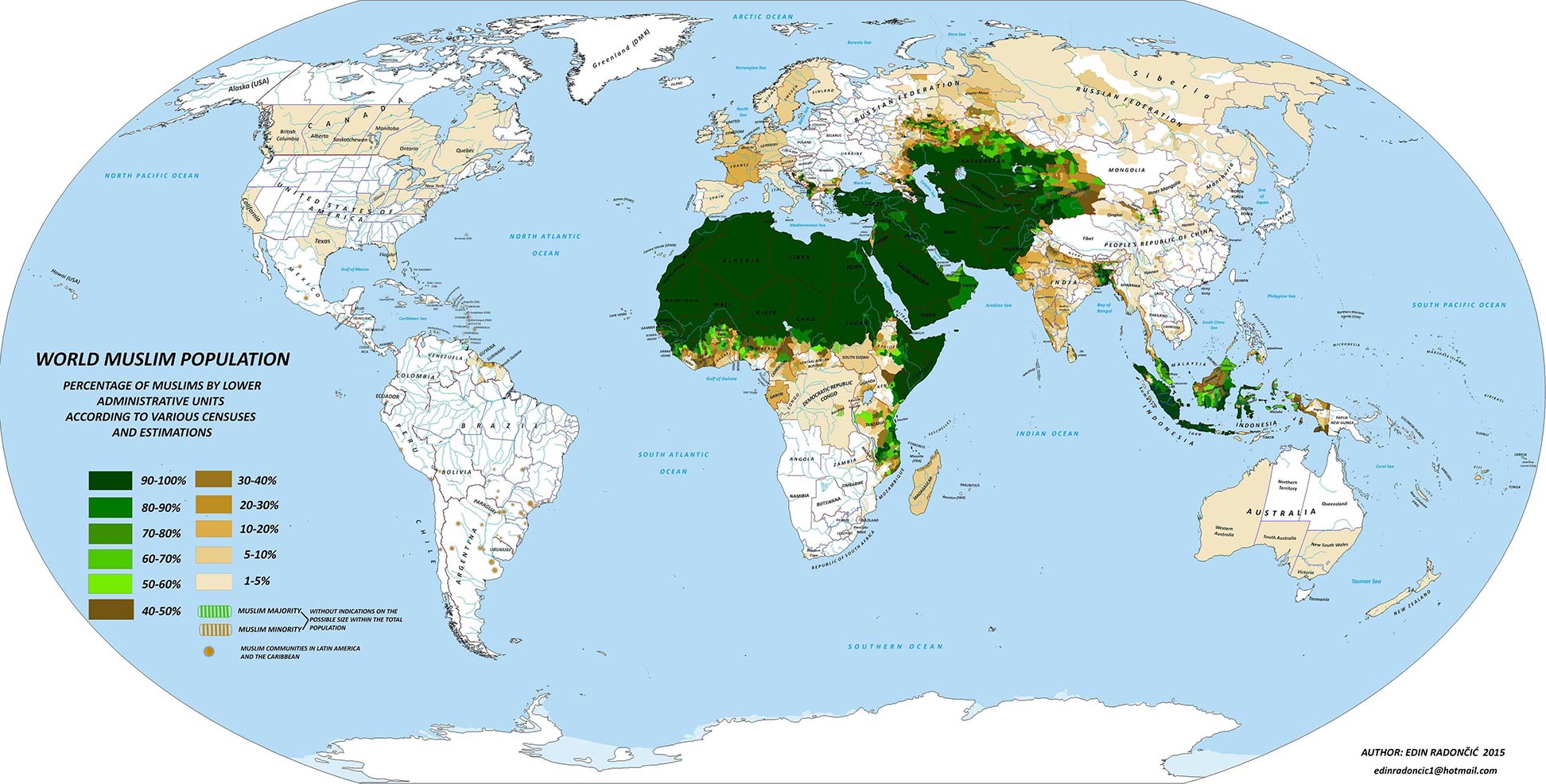

To gain this influence, IS established state institutions and relied on the appeal of its caliphate. According to the The Princeton encyclopaedia of Islamic political thought, a caliphate can be described as an Islamic state led by a caliph who is a successor of prophet Muhammed and who is the political and religious leader of the ummah (the entire Muslim community). IS used its statehood and caliphate to achieve its salafi-jihadist goals. Indeed, it aimed to return to the true Sunni Islam when all Muslims only respected Allah’s shari’ah. IS also promoted violent actions against non-Muslims so as to expand its caliphate and spread the shari’ah all over the world. In fact, a key concept of salafi jihadism is al-wala’ wa-l-bara’ which refers to the loyalty between Muslims and the disavowal and hostility towards non-believers. It is intertwined with the notion of takfir which means that some Muslims may be declared apostates if they don’t comply with the shari’ah. IS’s ultimate goal is to engage in a clash of civilizations that will precipitate the End of Times and the Day of Judgement. We will further develop the notions of jihad and End of Times later in this paper.

My research paper will attempt to provide an answer to the following question: To what extent IS’s statehood and the instauration of a caliphate enabled it to spread its conception of Islam all over the world?

First of all, we will analyse how IS implemented state institutions within the frame of a caliphate in order to sustain its expansion and reinforce its religious legitimacy. Then we will study how its statehood and caliphate participated both in the construction of its identity in opposition to the West and in the promotion of its uniqueness in the leadership of the ummah. Finally, we will understand that IS’s ability to achieve its goals was limited by its conceptions of statehood and caliphate.

I. Establishment of a functional state under the form of a caliphate to sustain its expansion and reinforce its religious legitimacy

A. How IS increased its power and implemented state institutions

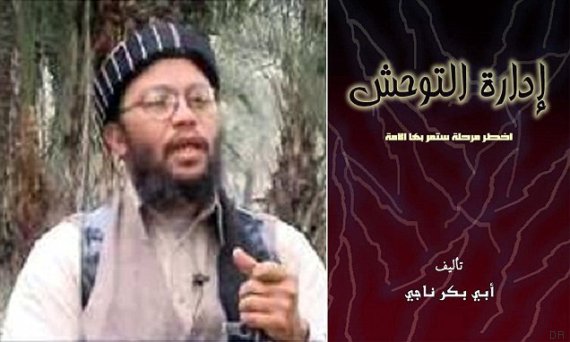

By implementing state institutions, IS sought to prevent internal collapse and sustain its war effort. In order to create a state or a caliphate it had to follow three stages according to Abu Bakr Naji’s Management of Savagery (2004) 1. He was an Egyptian Islamic strategist who worked for al-Qaeda propaganda until his death in 2008.

1. “Power of vexation and exhaustion” (1st stage)

During this first phase, IS carried out terrorist attacks and targeted economic and strategic assets in Iraq and Syria. It aimed to concentrate state troops in specific places such that they left other areas, thus creating a power vacuum. Weakening state infrastructures decreased states’ ability to control their whole territory. Therefore, IS could step into the breach of the breakdown of order so as to polarize society along ethnic and religious lines. Thereby it forced the population to choose a side, thus fuelling a violent civil war in which IS’s degree of savagery will be deterrent for people to join the other side.

2. “Administration of Savagery” (2nd stage)

In this second stage, IS took advantage of the chaos it had created to establish itself in Syria and Iraq. In order to gain popular support, it set up institutions to curtail this anarchy. To this end it had to follow the 12 points listed by Naji. Among them we notably find the provision of welfare that includes the supply of food, electricity, medical treatments and education. In big cities, such as Raqqa, public services were guaranteed by Islamic Services Committees.

Shari’ah Institutes were in charge of education so as to spread IS ideology. Moreover, in order to gain popular support IS guaranteed internal security, with its jihadists performing police work, and protection against external threats. Therefore, IS could implement a sort of social contract with the population. Besides, during this “Administration of Savagery” stage, IS built a fighting society by training the young to spread savagery and perform Naji’s first stage. According to Fawaz Gerges, following the 12 points of Naji allowed IS to thrive and draw support from rural and poor Sunni communities 2. IS’s gain of popularity could also be felt abroad as young people in poor regions of Tunisia for example were attracted by the authenticity, the justice and the order that IS embodied 3.

3. “Power of Establishment” (3rd stage)

Once these first two stages completed, IS established political, juridical, intelligence and economic institutions.

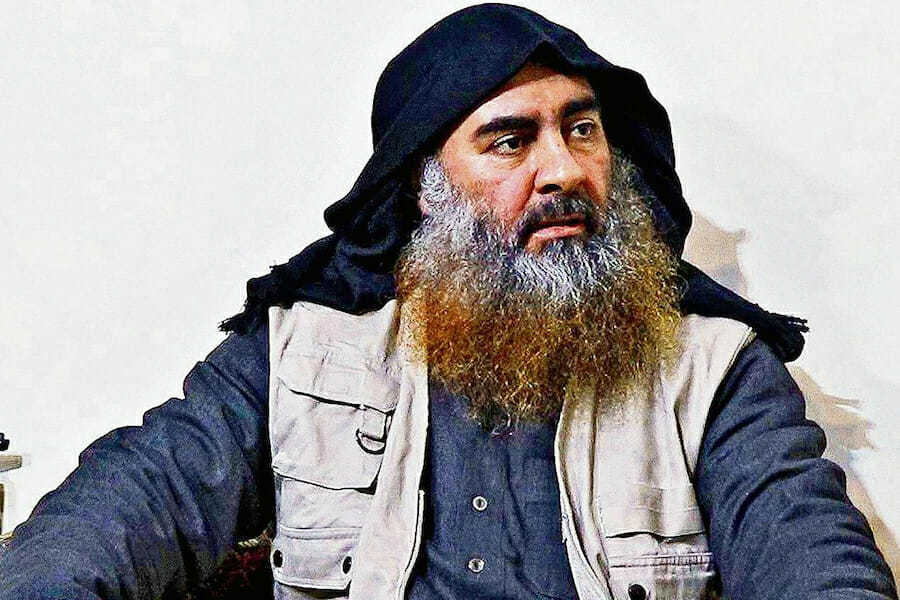

As IS’s caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had executive power and could be considered as a head of state.

He was surrounded by a cabinet of diwans (ministries) and he appointed governors in the 12 wilayahs (governorates or provinces). Among the various diwans we can find those of education, public services, tribal outreach, finance and currency system, agriculture, military and defence, enforcement of public morality… For instance, these diwans implemented regulations on fishing, agricultural plans or vaccinations programs 4. In order to make these institutions work well, IS relied on the experience of former Saddam Hussein’s officers. Indeed, out of the 12 wilayahs, 7 were governed by veterans of Hussein’s regime, and one of al-Baghdadi’s two deputies was a former Iraqi major named Saud Mohsen Hassan 5.

So as to uphold the shari’ah, a Consultative Council (shura) verified the compliance of IS leaders’ decisions with Allah’s law. IS’s leaders also had to take account of the fatwas issued by the Council of Muftis which is made up of Islamic jurists who discuss the interpretation of the shari’ah 6. Besides, there were shari’ah courts in almost every city. They applied punishments specified in the Quran in case of violations of Allah’s hudud (“limit”)7. For instance, thieves had their hands cut 8 and fornicators received hundred whiplashes 9.

Furthermore, intelligence institutions spied on the population. Missionary offices (da’wah offices) were present in almost every city. They not only sought to spread Islam but also to recruit local inhabitants. The latter then collected intelligence about potential rivals or traitors. IS also spied on its leaders and decision-makers in the wilayahs. One of IS’s masterminds was a former colonel of Saddam Hussein’s intelligence service named Samir Abd Muhammad al-Khlifawi (known under Haji Bakr). The latter designed a blueprint to build an “Islamic Intelligence State”. He imagined a state apparatus with an intelligence agency similar to the Stasi. Despite his death in 2014, IS implemented parts of his plan for surveillance, espionage and suppression in order to take over Syria and Iraq. Moreover, the seizure and plunder of banks and state offices allowed IS to collect all sorts of information about the population living on its territory 10.

Besides, IS’s functioning hinged on a strong economic structure. In fact, the relative economic stability that its bureaucracy ensured attracted local businessmen 11. IS’s revenues amounted to allegedly $900 million in 2015 12. Most of it stemmed chiefly from confiscations, taxes and oil extraction. Taxation played an important role in IS’s plan since people’s compliance with taxes proved their belonging to its community. Taxes amounting to $100 to $200 were levied every month on pharmacies, and there were fees for school registration and garbage disposal for instance. Furthermore, taxation was a flexible means for IS to compensate potential losses from airstrikes on its oil infrastructures 13. The rest of IS’s revenues came from lootings, ransoms and remittances received by people living on its territory 14. IS also took part of the wages sent by the Iraqi government to its employees working on IS’s territory 15. Besides, IS relied greatly on local Sunni tribes that had established economic networks in the region. For instance, oil was smuggled through networks created in the 1990s when Iraq was under a UN embargo after the Gulf War 16.

B. IS’s Caliphate: claiming a continuity with a glorious past

From a religious perspective IS’s statehood took the form of a caliphate in order to reinforce its religious legitimacy and overall influence.

1. What is a Caliphate and what were the recent evolutions regarding a potential re-establishment?

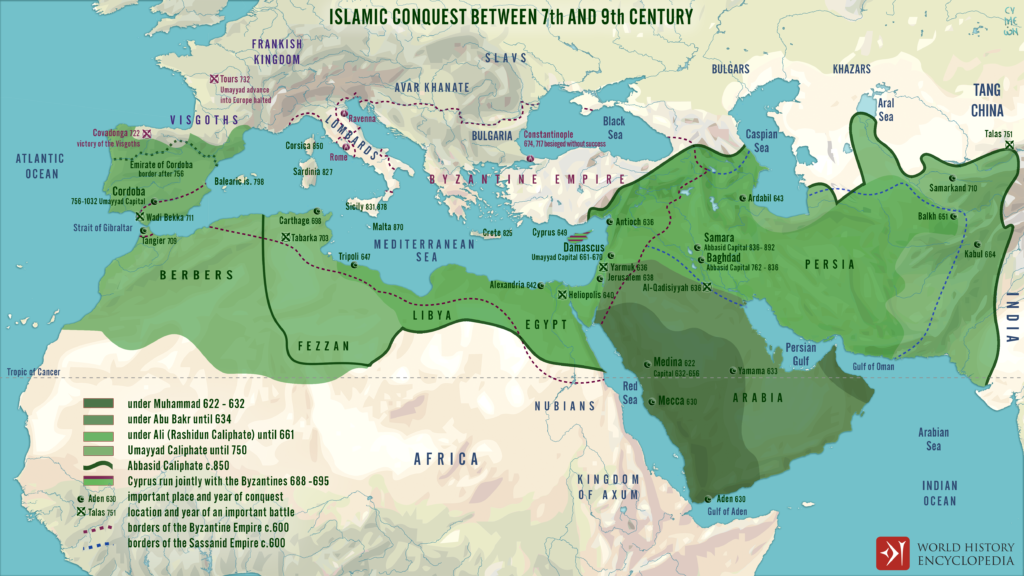

As mentioned in the introduction, a caliphate is an Islamic state led by a caliph who is a successor of prophet Muhammed and who is the political and religious leader of the ummah. However, the caliph doesn’t have any special connection with Allah, he is fallible like all human beings and cannot interpret the Quran or pass laws. However, his executive role includes representing the ummah, leading armed forces, upholding laws, defending holy places and being the first officiant of collective prayers for instance 17. Nonetheless, there have been regular disagreements regarding the identity of the to-be caliph. In fact, during the 11th century there were three caliphates of which the Abbasid caliphate (750-1258) was the most powerful. The two others were the Fatimid caliphate (909-1171) and the Umayyad caliphate (929-1031), which was in exile in Cordoba after its defeat against the Abbasids. However, in March 1924, the last caliphate, the Ottoman one, was abolished by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first Turkish president (1923-1938).

Nevertheless, the foundation of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt in 1928 revived the militancy for the establishment of a caliphate. It is even a major objective of the organisation Hizb ut-Tahrir (HT) that originated from a scission with the Muslim Brotherhood in 1953 18. Since then some attempted to claim the title of caliph but without explicitly mentioning it such as Mullah Muhammed Omar who led the Taliban in Afghanistan.

He founded the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan in 1996 and was called Commander of the Faithful by his fellow Taliban. However, his legitimacy was questioned since he is not a descendent of the Quraysh which is prophet Muhammed’s tribe. It is allegedly a condition for a Muslim to be caliph19.

2. How did IS implement its caliphate?

IS declared the existence of its caliphate on June 29, 2014, and since then tried to embody continuity with a glorious past. In every Muslim’s mind, the Rashidun caliphate that followed the death of prophet Muhammed in 632 represents a golden age 20. The four caliphs of this caliphate were the “Rightly Guided”. It is therefore an ideal that IS endeavours to reproduce.

For instance, IS’s leader greatly imitated the first Rashidun caliph Abu Bakr, starting with his name: Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. His accession speech on July 4, 2014, in Mosul’s mosque, also greatly resembled Abu Bakr’s one.

Indeed, they both particularly stressed that they subjected themselves to the judgement of all Muslims under their rules. They also acknowledged their fallibility and agreed to be deposed if they didn’t comply with religious imperatives 21. Besides, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi declared being a descendent of the Quraysh tribe. IS also informed that he was chosen by a shura i.e. a consultation of Muslims, even though those who made the decision were only IS leaders. Someone can also be appointed caliph if he is a Holy family’s heir or if the previous ruler directly appoints him (nass) 22. According to salafi-jihadism, the instauration of a caliphate is the result of a short and intensive process 23. That’s why IS drew a parallel between its military conquests and those of the Rashidun caliphs in Mesopotamia, Persia and the Maghreb 24.

II. Assertion of its identity in opposition to the West and promotion of its uniqueness in the leadership of the Muslim world

A. Rejection of the Westphalian order

As we saw, IS assumed some state-like functions. However, it categorically rejected the Westphalian visions of the world and of statehood. The Westphalian state system refers to sovereign states that own the monopoly of force within their mutually recognized territories. They maintain diplomatic relations and abide by international laws that they created through treaties and customs. In the Westphalian system, states pledge not to intervene in others’ domestic affairs 25.

1. Satisfying only some criteria to be a state proper

In order for entities to enter the Westphalian order they have to satisfy some criteria that can be found in the first article of the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (1933). IS satisfied the first three requirements but not the last one.

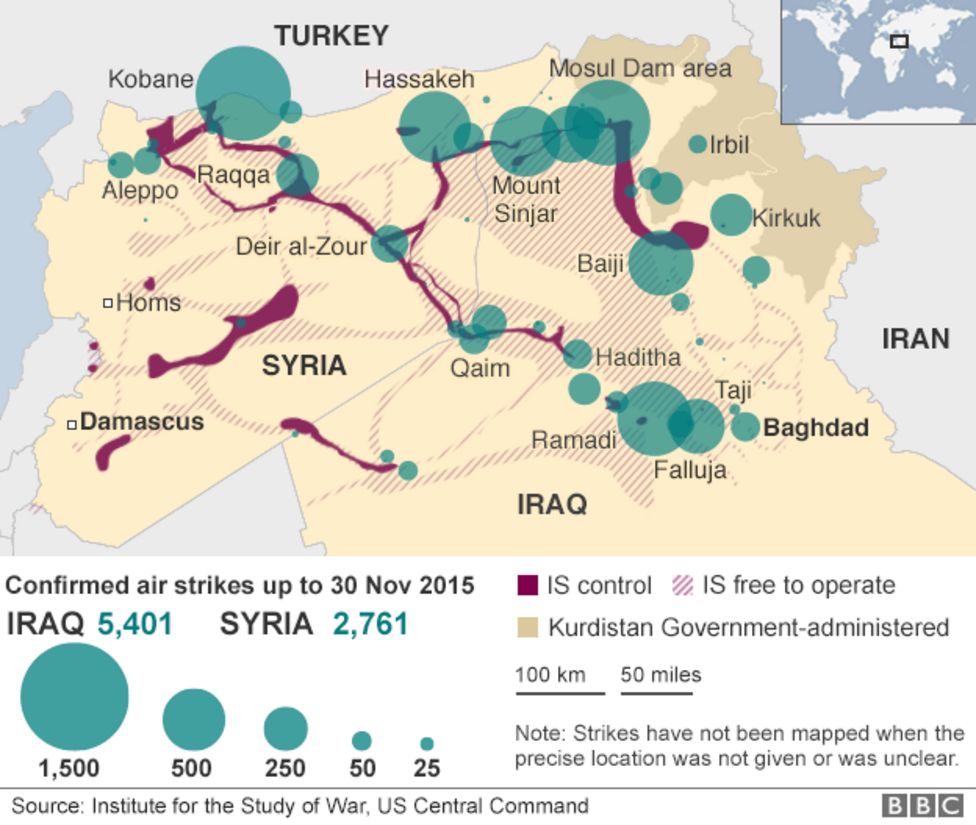

In fact, IS exercised an effective domination over a permanent population of around 8 million inhabitants26. The latter lived on a defined territory which allowed IS to fulfil the second criteria of the Montevideo Convention. The highest level of territorial control and influence in Syria and Iraq was reached in November 2014 and September 2015 with almost 397,000 km² (bigger than the size of Germany)27. Even though there are some diwans in Cyrenaica and Tripoli regions (Libya), these are only “franchises” that are not part of the caliphate because they first of all rely on local tribes’ power28. Furthermore, in Syria and Iraq, IS acted like an effective government. In fact, it owned the monopoly of force which allowed it to uphold the rights and duties it had imposed29. Besides, IS was a sovereign entity due to its independence from other states and its exclusive and unlimited authority on its territory and in its domestic affairs30. However, IS couldn’t enter the Westphalian state system because it didn’t respect the fourth condition of the Montevideo Convention: it refused to build official international relations with state actors. Therefore, it couldn’t take actions with legal effect on the international stage31. As we will see, IS refused to comply with international laws that are central to the Westphalian order because it deemed them as illegitimate.

2. Was the Islamic State actually a state?

In light of what has just been discussed, IS’s statehood can be questioned. There are actually two schools of thought on this issue: those who endorse the Constitutive theory arguing that IS was not a state, and those who refer to the Declaratory theory which confirms IS’s statehood32.

According to the Constitutive theory, a state can only be considered as such and exist legally when it is recognized by other states. For IS to be a state, it had first to adhere to international laws33. However, it repeatedly transgressed them and violated ius cogens norms by committing war crimes and crimes against humanity like the genocide against Yazidis. Thus recognizing its statehood would amount to approving of international crimes. Moreover, since IS broke laws regarding the integrity of the Syrian and Iraqi territories then it made it illegal to build relations with it. According to Robert Sloane, other states had to express a formal approval of its statehood otherwise IS would have been bound to remain a non-entity34.

On the contrary, the Declaratory theory emphasises the functional aspects of IS’s statehood. According to Quinn Mecham, in order to assess IS’s level of statehood we ought to focus on the effectiveness with which IS ruled its territory and population. In order to measure it, she created 6 criteria: tax and labour acquisition, defining and regulating citizenship, managing international relations, providing domestic security, providing social services and facilitating economic growth35. Even though it intentionally performed badly in the management of international relations, IS met most of the other criteria. IS could thus be considered as a para-state since it was a governmental entity that wielded power within the international frontiers of de jure states (Syria and Iraq) and outside the areas of effective control by these states. Nonetheless, IS couldn’t be defined as a de facto state since it didn’t seek to become a de jure state36.

3. How could the Islamic State be considered as a threat to the Westphalian order?

IS challenged the Westphalian system by proposing an alternative vision of statehood and of the world order.

As a matter of fact, it promoted the classical Islamic approach where religion should be the basis of the world order, not politics. Therefore, any state that didn’t draw its legitimacy from Allah or that didn’t follow the shari’ah was considered illegitimate by IS. Thereby many Muslim countries, who didn’t pledge allegiance to IS, belonged to the non-Muslim world (dar al-harb). A holy war should destroy this world in order for IS to unite the whole Muslim world (dar al-Islam) under its caliphate 37. IS’s vision of the world order relied on belligerency whereas the Westphalian order hinges on diplomatic relations to foster peace. Besides, IS rejected the secular notion of nation-state and believed in a single Islamic world community that would eclipse nationalism and race 38. Thereby IS challenged the traditional conception of statehood that takes nationalism as the source of its legitimacy. Furthermore, IS’s statehood rested upon the notion of dawla. Indeed it used it in its name: al-Dawla al-Islamiyah. Dawla refers to the secular political organisation of the ummah within the caliphate 39. Its simple translation into “state” misses its essence because dawla implies a flexible establishment that does not depend on control over a specific geographic area. In fact, it first and foremost connotes a dynastic-based state. It implies that the disappearance of the dynasty puts an end to the state’s existence: the word dawla refers to an alternation of periods of fortune and misfortune 40. For instance, the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258) was called Abbasid dawla or House of Islam. We will see later in this paper that IS’s use of the word dawla was somewhat hypocritical since its source of power lied primarily in its territorial conquests.

B. Gathering the ummah behind IS’s leadership

IS used its caliphate as a justification for claiming the leadership of the ummah. Its caliphate represented thus the basis from which it aimed to conquer the world, spread the shari’ah and eventually reach the End of Times.

1. The Bay’ah

In order for IS to gain more support from Muslims and legitimize its authority, it demanded the bay’ah of all Muslims. It is an oath of allegiance which could be addressed to either the caliph (al-Baghdadi) or the Islamic State itself. Demanding the bay’ah was a means to delegitimize other organisations like al-Qaeda and ensure that every Muslim falls in line. Indeed, if one didn’t give his bay’ah, one would have been considered as an apostate (takfir) who would deserve to die. For instance, some jihadists of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb split to join IS. In fact, IS’s caliphate entailed that the legitimacy of all organizations, states and emirates was made void 41.

2. The Hijrah

Besides, so as to increase its power IS needed to attract Muslims from all around the world to come and fight in its ranks. Therefore, it requested their emigration from their country of origin (hijrah). Unlike al-Qaeda, IS controlled an easily identified territory and promised material comfort to its future recruits 42. Hence it facilitated potential fighters’ hijrah and its number of soldiers amounted to tens of thousands 43. IS described hijrah as a way for Muslims to withdraw from corrupted and un-Islamic societies. Therefore, it viewed hijrah as both a physical and spiritual migration towards its caliphate. Demanding Muslims’ hijrah aimed to force them to choose a side: either they are with it or against it.

3. The Jihad and the End of Times

IS sought to gather Muslims in a same Islamic space (hijrah) i.e. its caliphate in order to then expand this space (jihad). The jihad is a duty for every Muslim: they have to make efforts to improve their faith as well as the society in which they live. For example, it can be done through waging war against disbelievers as the Quran states it 44. However, IS overemphasized this violent option to foster war against those who refused its religion and authority, thereby spreading Islam and the shari’ah all over the world. Jihadism was part of a broader goal that aimed to reach the End of Times. This End of Times would cause the death of all human beings. However, it would be followed by the Day of Judgement which symbolizes the beginning of an endless life. According to the Quran, those who believed in Allah and did good deeds will live endlessly in Paradise, whereas those who sinned or had another religion will forever live in Hell 45,46. IS’s goal was to precipitate this End of Times by doing the jihad against infidel armies and by conquering as much territory as possible. Such a holy war should culminate in an apocalyptic clash that would cause the End of Times. According to IS’s propaganda, this battle could take place either in Rome, Jerusalem, Damascus or in the small Syrian city of Dabiq47.

III. Claiming statehood and a caliphate: a limited strategy for IS

A. Impossibility to remain a threat to the Westphalian order

IS’s alternative conception of statehood was a menace to the Westphalian order and the latter couldn’t tolerate it. Therefore, IS could only become part of the Westphalian order otherwise it would get destroyed by it.

1. Integration in the Westphalian order as a condition for viability

In fact, the integration in the Westphalian order was a necessity for IS to ensure its viability as Robert Delahunty argues in “An Epitaph for ISIS? The Idea of a Caliphate and the Westphalian Order” (2016). Providing welfare to its population, as we studied it, was essential to spread its ideology and draw support. Islamic states under prophet Muhammed and the Rashidun caliphate experienced military successes and economic prosperity that improved their populations’ welfare. Such level of development is believed to have been achieved through faithfulness to the original paradigm. Therefore, if IS’s caliphate doesn’t manage to bring the same level of welfare, its faithlessness will be pointed out, thus making it lose legitimacy.

Joining the Westphalian order would have allowed IS to thrive economically and attract large numbers of Muslims, thus reinforcing its viability. Turning into a de jure state would also have saved resources used to wage wars and maintain its security. Besides, integrating the Westphalian order would have facilitated trade and attracted investments, thereby improving the welfare of its population. However, as we already studied, IS endeavoured to build its identity in opposition to the West: rejecting the Westphalian order was the only option. Nonetheless, it might have been part of a broader strategy to provoke foreign military interventions and attract fighters by promising them to become martyrs48.

2. US policy that endeavoured to “degrade and ultimately destroy” IS

In fact, following IS’s rise in Syria and Iraq, on September 11, 2014, the US President Barack Obama set out his plan that aimed to “degrade and ultimately destroy” IS49. The US strategy relied chiefly on air strikes targeting IS’s fundamental state institutions. Indeed, they were the basis from which it could sustainably carry out its actions and grow stronger. Therefore, IS’s claim to statehood made it easier for its enemies to identify key targets in order to defeat it.

3. IS’s territory: a denied weakness

The US-led coalition (Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve), that started its operation at the end of 2014, aimed to inflict territorial losses on IS. To do so Obama’s plan included an increased support to the Peshmerga, the Syrian Democratic forces and the Iraqi state forces. This support has taken the form of “training, intelligence and equipment”50. IS’s territory was the result of military conquests that highlighted its power and legitimacy to lead the Muslim world. In fact, IS’s narrative rested upon jihadism that would attract fighters to reach the End of Times. Therefore, military defeats would question its legitimacy and the viability of its project. However, IS denied such weakness since it was allegedly a dawla whose power didn’t rely on the occupation of a specific territory. Besides, the Internet allowed Muslims to give their bay’ah from anywhere on Earth, thereby allowing IS to claim control over different regions of the globe. Therefore, theoretically, IS could maintain its presence and influence all over the world despite military defeats.

B. Salafi-Jihadism: a limit to IS caliphate’s influence on the ummah

1. IS’s caliphate: an actual rupture with the glorious past

According to A.K. Newell51 there are several reasons why IS’s caliphate represented a rupture with the Islamic state of prophet Muhammed and the Rashidun caliphate. Indeed, IS’s caliphate was a police state that cracked down on its population, spied it, tortured people and sent them to jail without trial. A caliphate such as the first one wouldn’t do that according to A.K. Newell. Besides, IS plundered the territories it conquered and didn’t seek to improve the life of local populations in the first place. The risk for IS was to be victim of the “Insurgency Resource Curse” and to turn into a criminal network which might have interfered with its plans to draw support from local populations52.

Moreover, in terms of international relations IS was isolationist due to its promotion of al-wala’ wa-l-bara’. Indeed, unlike prophet Muhammed, it didn’t resort to diplomacy and didn’t encourage foreigners to visit and work in its territory53. As shown in Safiur-Rahman al-Mubarakpuri’s biography of the prophet, the latter signed several treaties with local tribes and religious communities. He also regularly sent letters of invitation to Islam to foreign leaders such as Al-Muqawqis the king of Alexandria and Egypt or Munzir ibn Sawa Al Tamimi who was the governor of the Persian Sasanian Empire54. Unlike IS, the prophet also had tolerance towards non-Muslim. For example? he designed the Constitution of Medina (622) in order to pacify relations between tribes living in Medina. As a result, the dhimmis, i.e. non-Muslims living under Muslim governance (essentially Jews at the time in Medina), had the same rights as Muslims and could worship freely their God55.

2. Rejection of the ummah’s diversity

Another problem with IS’s caliphate was its sectarian vision of the world which hindered its ability to gather the entire ummah under one flag. IS wanted all Muslims to embrace Salafism. However, over the centuries the ummah decentralized itself from the Middle East which resulted in the apparition of “regional ummahs” with a plurality of histories, cultures and societies. For instance, as Riaz Hassan points it, in Indonesia and Southeast Asia the practice of Islam is defined as malleable, syncretic and multi-vocal. On the opposite, in Saudi Arabia this practice stresses moral severity and aggressive piety56. Consequently, IS’s project to impose Salafism to the entire ummah lacked attractiveness and was thus doomed from the start.

3. IS’s focus on the near enemy

Furthermore, unlike al-Qaeda that focused primarily on the far enemy (the West), IS based its doctrine on the struggle against a near enemy. It wanted to purge Islam of Muslims who didn’t abide by the shari’ah by excommunicating them (takfir) and being hostile towards them (al-wala’ wa-l-bara’). This strategy isolated IS from the rest of the ummah and reduced its recruitment ability. By bringing too much light on itself, its number of enemies increased. Al-Qaeda made the mistake in 2001 and bore the cost of it. That’s why in 2012-2013 al-Zawahiri demanded ISI (it became IS in 2014) to restrict itself to Iraq and to avoid using too much violence. Even though its focus on the near enemy reduced its project’s attractiveness, it was part of a plan to foster civil wars over the world. By breaking down societies, it would have forced people to choose a side as it did in Iraq and Syria during the first stage of the Management of Savagery.

4. A violent minority rejected by the rest of the ummah

Muslims didn’t give their bay’ah to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi because they didn’t feel represented by the violent minority of salafi-jihadists he led. According to the journalist Bruce Livesey, salafi-jihadists were only 1% of the ummah in 200557. Even though the period 2010-2013 was characterized by a doubling of the number of fighters they still remained a minority in 2014-201558. The silent majority of Muslims didn’t see why a violent and more visible community should feel entitled to represent them. Even though most of them would like to make the shari’ah the official law in their country, they disapproved of the means used to implement it by IS59. Furthermore, Muslim scholars were rather unanimous to denounce IS’s actions and their non-representativeness of the ummah’s views. For instance, in September 2014, 126 political leaders and scholars published an open letter addressed to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi condemning IS’s violence and totalitarian tendencies60. Besides, Osman Bakhach, director of Hizb ut-Tahrir’s central media office, points out that the caliphate should not be re-establish with blood, explosions and takfir61.

5. Al-Qaeda: a persistent rival

IS’s strategy to establish a caliphate had the objective of getting rid of potential rivals by forcing them to give their bay’ah to the caliph. However, it had the opposite effect with al-Qaeda. Originally IS was al-Qaeda branch in Iraq between 2004 and 2013-2014. Nonetheless, strategic and sometimes ideological disagreements were regular between the two groups. It even started in 1999 with the strong distrust that Abu Musad al-Zarqawi (sort of founder of IS in 1999) and Osama Bin Laden had for one another. Therefore, al-Qaeda couldn’t stand to see its legitimacy thrown into doubt by the proclamation of IS’s caliphate. Ayman al-Zawahiri, al-Qaeda’s leader, thus asserted that Mullah Muhammed Omar, who founded the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan in 1996, was the only caliph as he received bay’ah first and thereby had a priority to claim to be caliph. However, Al-Zawahiri’s stance was a bit hypocritical because in 1996 he disagreed with Omar’s claim to be caliph since he hadn’t established yet a proper caliphate and was not a descendent of the Quraysh tribe.

Conclusion

We have thus come to the conclusion that IS resorted to state institutions and a caliphate in order to gain power with the aim of spreading its conception of Islam all over the world. Indeed, its sophisticated governance allowed it to avoid a potential internal collapse and draw support for its war effort. Moreover, IS’s statehood was a means to reinforce its ideological opposition with the Westphalian order by proposing an alternative state model. Besides claiming a caliphate was a way to assert its religious legitimacy in the leadership of the Muslim world. Indeed, IS used its caliphate as the reason why the ummah had to join it and eventually do the jihad to reach the End of Times. Nonetheless, this strategy of claiming statehood and a caliphate was somewhat limited. In fact, IS’s conception of statehood posed a threat to the Westphalian order. The latter then undertook actions to rid itself of it by targeting IS state institutions. IS’s ability to gain power was also limited by its salafi-jihadist conception of the caliphate. It didn’t manage to draw massive support from the ummah that didn’t feel represented by this violent and divisive minority. It even triggered a reaction from its rival al-Qaeda that rejected its claim and supported another caliphate instead.

However, IS pioneered a model of organisation that has exported itself in Nigeria with Boko Haram or in the Philippines with the Abu Sayyaf group for instance. This model fits these jihadist organisations that seek to fuel violent civil wars and force people to choose a side.

Sources

- Naji, Abu Bakr. Management of Savagery: The Most Critical Stage Through Which the Islamic Nation Will Pass. 2004.

- Gerges, Fawaz. ISIS: A History. Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Kuznetsov, Vassily. The Islamic State: Alternative Statehood? Russia in Global Affairs, December 2015. https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/the-islamic-state-alternative-statehood/.

- Al-Tamimi, Aymenn. The Evolution in Islamic State Administration: The Documentary Evidence. Perspectives on Terrorism, vol. 9, n°4, August 2015.

- Hendawi, Hamza, et Qassim Abdul-Zahra. Islamic State Is Led by More than 100 of Saddam’s Former Officers. http://www.timesofisrael.com/islamic-state-led-by-saddams-former-top-officers/.

- Nanji, Azim A. “Mufti”. In John L. Esposito, The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Al-Tamimi, Aymenn (2015).

- Surah Al-Ma’idah – 5:38. https://quran.com/5/38?translations=131.

- Surah An-Nur – 24:2. https://quran.com/24/2?translations=131.

- Reuter, Christoph. Islamic State Files Show Structure of Islamist Terror Group, Der Spiegel,April 15, 2015. https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/islamic-state-files-show-structure-of-islamist-terror-group-a-1029274.html.

- Sherlock, Ruth. What is Islamic State trying to achieve? The Telegraph, June 2015. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/islamic-state/11665474/What-is-Islamic-State-trying-to-achieve.html.

- Solomon, Erika. Isis Inc: Jihadis Fund War Machine but Squeeze ‘Citizens’. Financial Times, December 15, 2015. https://www.ft.com/content/2ef519a6-a23d-11e5-bc70-7ff6d4fd203a.

- Al-Tamimi, Aymenn (2015).

- Lypp, Jacob. Understanding ISIS: the political economy of war-making in Iraq. SciencesPo PSIA – Kuwait Program, 2016. https://www.sciencespo.fr/kuwait-program/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/KSP_Paper_Award_Fall_2016_LYPP_Jacob.pdf.

- Al-Tamimi, Aymenn (2015).

- Woertz, Eckart. How long will ISIS last economically? Barcelona Centre for International Affairs, CIDOB. October 2014.

- Kennedy, Hugh. Caliphate: The History of an Idea. Basic Books, 2016.

- Mohamed Osman, Mohamed Nawab. ISIS’ Caliphate Utopia. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, n°143, July 2014. https://dr.ntu.edu.sg/bitstream/10356/102988/1/RSIS1432014.pdf.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2016).

- Afsaruddin, Asma. The First Muslims: History and Memory. Oneworld, University of Michigan, 2008.

- Delahunty, Robert J. An Epitaph for ISIS? The Idea of a Caliphate and the Westphalian Order. SSRN Electronic Journal, 2016. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.2139/ssrn.2868199.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2016).

- Maher, Shiraz. Salafi-Jihadism: The History of an Idea. Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2016).

- Westphalian State System. Oxford Reference, doi:10.1093/oi/authority.20110803121924198.

- Kuznetsov, Vassily (2015).

- Breteau, Pierre, et Jules Grandin. Mapping the War on ISIS in Syria and Iraq since the Establishment of the “Caliphate”. Le Monde – Les Décodeurs, July 4, 2019. https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/visuel/2016/05/31/mapping-the-war-on-isis-in-syria-and-iraq-since-the-establishment-of-the-caliphate_4929599_4355770.html.

- Kuznetsov, Vassily (2015)

- Potyrala, Anna. “Islamic State – Disputed Statehood” in Sroka, Anna and al, Radicalism and Terrorism in the 21st Century, 2017. https://www.peterlang.com/view/9783631706381/xhtml/chapter06.xhtml.

- Ehrlich, Ludwik. Law of Nations. 1927.

- Potyrala, Anna (2017).

- Janik, Ralph. Is the Islamic State a State?, Völkerrechtsblog, June 2016, https://voelkerrechtsblog.org/articles/is-the-islamic-state-a-state/.

- Shany, Yuval, et al. ISIS: Is the Islamic State Really a State?. The Israel Democracy Institute, September 2014, https://en.idi.org.il/articles/5219.

- R. D. Sloane, The Changing Face of Recognition in International Law: A Case Study of Tibet, “Emory International Law Review” no. 16, 2002, p. 116.

- Mecham, Quinn. How Much of a State Is the Islamic State?, Washington Post, February 5, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2015/02/05/how-much-of-a-state-is-the-islamic-state/.

- Delahunty, Robert J. (2016).

- Crone, Patricia. God’s Rule: Government and Islam ; [Six Centuries of Medieval Islamic Political Thought]. Columbia Univ. Press, 2004.

- Kaneva, Nadia; Stanton, Andrea. An Alternative Vision of Statehood: Islamic State’s Ideological Challenge to the Nation-State. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, June 2020, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1780030.

- Kuznetsov, Vassily (2015).

- Ibn Khaldûn, Ibn, et al. The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History – Abridged Edition. N. J. Dawood, Princeton University Press, 2015. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1515/9781400866090.

- Bunzel, Cole. From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State. The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World , n°19, March 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/The-ideology-of-the-Islamic-State.pdf.

- Kaneva, Nadia and Stanton, Andrea (2020).

- Kuznetsov, Vassily (2015).

- Surah Al-Anfal – 8:39. https://quran.com/8/39?translations=131.

- Surah Al-Baqarah – 2:81 and 2:82. https://quran.com/2/81-82?translations=131.

- Surah Ali ’Imran – 3:85. https://quran.com/3/85?translations=131.

- McCants, William F. The ISIS apocalypse: the history, strategy, and doomsday vision of the Islamic State. First edition, St. Martin’s Press, 2015.

- Naji, Abu Bakr (2004).

- Young, Matt. Obama’s ISIS Speech: How the US Will Degrade and Destroy Islamic State. NewsComAu, September 11 2014. https://www.news.com.au/national/obamas-isis-speech-how-the-us-will-degrade-and-destroy-islamic-state/news-story/6fa9dd6c2916bfbc4915afe7a6437949.

- Young, Matt (September 11, 2014)

- Newell, A. K. Accountability in the Caliphate. 2017.

- Ahram, Ariel I. Can ISIS Overcome the Insurgency Resource Curse? Washington Post, July 2, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2014/07/02/for-isis-its-oil-and-water/.

- Crone, Patricia (2004).

- al-Mubarakpuri, Safiur-Rahman. When the Moon Split. Darussalam, 2011.

- Ahmad, Barakat. Muhammad and the Jews: a re-examination. Vikas, 1979.

- Hassan, Riaz. “Globalization and the Islamic Ummah”. Inside Muslim minds, Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2008.

- Livesey, Bruce. Special Reports – The Salafist Movement. Frontline, January 25, 2005. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/front/special/sala.html.

- Jones, Seth G. A persistent threat: the evolution of Al Qa’ida and other Salafi jihadists. RAND, 2014.e

- Pew Research Center, The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project, April 30, 2013. https://www.pewforum.org/2013/04/30/the-worlds-muslims-religion-politics-society-overview/.

- Open Letter to Baghdadi to Dr. Ibrahim Awwad al-Badri Alias “Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi” and to the Fighters and Followers of the Self-Declared “Islamic State”. Issuu, September 19, 2014. https://issuu.com/openlettertobaghdadi/docs/arabic_english_open_letter_to_baghd.

- Mohamed Osman (2014).

13 Comments

Conni · 1 July 2023 at 10:25 am

Your blog provided us with valuable information to work with. Each & every tips of your post are awesome. Thanks a lot for sharing. Keep blogging,

Madel · 10 June 2023 at 3:55 am

I have read your excellent post. This is a great job. I have enjoyed reading your post first time. I want to say thanks for this post. Thank you…

rama · 17 March 2023 at 4:40 am

I am overwhelmed by your post with such a nice topic. Usually I visit your blogs and get updated through the information you include but today’s blog would be the most appreciable. Well done!

rama · 18 June 2022 at 10:10 am

whoah this blog is wonderful i really like reading your articles. Keep up the great paintings! You realize, a lot of people are hunting round for this info, you could help them greatly.

lina · 16 June 2022 at 12:47 pm

I have read so many posts about the blogger lovers however this post is really a good piece of writing, keep it up

Humiliation in International Relations – geopol-trotters · 8 January 2024 at 3:14 pm

[…] There needs to be a mix between multilateralism and regionalism, as Kofi Hanan suggested in 2012 in his role of mediator in Syria. […]

TURKEY and RUSSIA : a strategic alliance ? - geopol-trotters · 4 February 2023 at 4:05 pm

[…] if Kurdish fighters (Peshmerga) fight Daesh and al Qaeda, Russia has refused to arm them in part because they oppose the Syrian government. […]

Al-Qaeda and Daesh in Africa - geopol-trotters · 28 December 2022 at 8:55 pm

[…] jihadist groups resort to violent means in order to seize power and establish a caliphate where people would live according to Allah’s law, the […]

[Part 3] Why did the US fail in Afghanistan (2001-2021) - geopol-trotters · 26 November 2022 at 7:41 pm

[…] remain a pariah state? If this question interests you, you may want to read my article on Daesh’s Statehood and Caliphate […]

Russia and the West: a New Cold War ? - geopol-trotters · 31 October 2022 at 8:49 pm

[…] that bombs rebels opposed to Bashar al-Assad’s regime, and the US-led coalition that fights terrorists and supports the rebels. This situation is comparable to the one of the 1980s in Afghanistan when […]

West Africa, a hotbed of narcoterrorism - geopol-trotters · 30 August 2021 at 5:17 pm

[…] (AQIM) to help with the transit of drug in the region even though it has pledged allegiance to Daesh. However in Libya AQIM is not in capacity yet to export drugs from its stronghold in Sirte. The […]

Religious communities in the Middle East - geopol-trotters · 25 August 2021 at 7:28 am

[…] Jihadism: The jihad is a duty for every Muslim: they have to make efforts to improve their faith as well as the society in which they live. For example, it can be done, but not solely, through waging war against disbelievers. […]

Nuclear proliferation and world stability - geopol-trotters · 4 August 2021 at 12:09 pm

[…] strikes are decided it would align with the goals these terrorist organisations. For instance, Daesh’s long term objective was to provoke the End of Times by sparking an apocalyptic conflict against infidel armies. It would have resulted in the death of […]