Should the EU get its own INTELLIGENCE AGENCY?

What you want to understand: 🤔

- What are the shortcomings of the EU’s current intelligence apparatus?

- Is a European Intelligence Agency the solution? What are the benefits and challenges?

- How to foster intelligence cooperation between member States?

- How to better integrate the fragmented EU intelligence community?

In his Strategic Compass, Josep Borrell calls for turning the EU’s recent “geopolitical awakening” into a more “permanent strategic posture” in order for the EU to be a global actor able to both defend its interests abroad and ensure security within its borders[1]. So as to efficiently make rational decisions for the Common Foreign and Security Policy, EU authorities can resort to intelligence, that is to say a four-step process comprising direction, collection, processing and dissemination of sensitive information that is used to support decision-making[2].

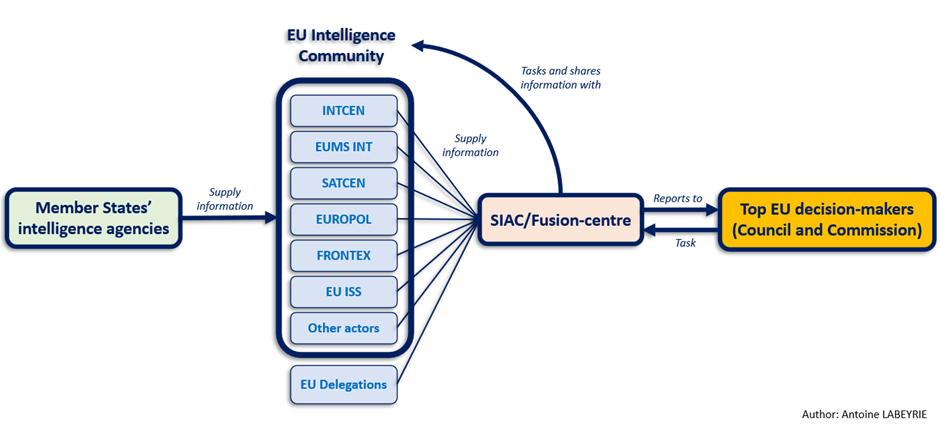

The EU’s intelligence community is made up of a wide range of independent actors loosely coordinated and of whom none performs all four steps of the intelligence process. Its main actors are the EU INTCEN[3] and the EUMS INT[4] that belong to the EEAS[5]. FRONTEX, EUROPOL and SATCEN[6] for example are other agencies of the EU intelligence community performing intelligence functions to support their own activities. The Council is the institution that more or less gives coherence to this conglomerate of entities since it is their main client and tasks them when it needs support for decision making. Besides, EU intelligence actors rely on member States for acquiring sensitive information as they don’t possess collection capacities of their own. In return, the EU endeavours to foster intelligence cooperation between its member States to reinforce security within its borders.

However, on several occasions like the 2014-Maiden Revolution, the 2015-Charlie Hebdo attack or the rapid withdrawal from Kabul in 2020, the European Union lacked intelligence in volume and quality to anticipate and better react to these crises and its member States didn’t cooperate sufficiently to prevent them[7],[8]. A solution often advocated for to improve the EU’s intelligence system is to establish a European intelligence agency on the model of national intelligence agencies.

In this paper, we will first analyse the shortcomings of the current EU’s intelligence system before discussing the benefits and drawbacks of establishing a European intelligence agency. Finally, we will propose alternative ways for improving the EU’s intelligence system.

I. What are the shortcomings of the EU’s current intelligence system?

A. Overreliance for information collection on member States that are not cooperative enough

As a matter of fact, no EU agency has collection capacities of its own, except for open-source intelligence and for FRONTEX’s specific activities, which makes the EU dependent on member States for obtaining sensitive information. The issue is that there is a gap between member States’ supply and the EU’s demand for information as it often arrives too late and is too vague to actually enlighten the EU’s decision-making process. Moreover, there is the possibility that member States only share biased and self-interested information.

Member States’ only partial cooperation in the field of intelligence may come from their distrust for what their partners might end up doing with the information they shared. They are also concerned about others’ free-riding and about the fact that if they share sensitive information, they will lose the privilege of holding it and therefore lose influence over their foreign partners. Small countries like Baltic States also fear that reinforcing European intelligence cooperation would undermine their bilateral intelligence cooperation with the US[9].

It is worth mentioning as well that the EU also relies on the US and NATO for information collection. Given the unreliability of the US leadership as illustrated under Trump’s mandate and more recently with the Biden administration’s unilateral decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan, it appears crucial for the EU to reduce its dependency on American intelligence.

B. A weakly structured and coordinated community lacking a common intelligence culture

The EU’s intelligence community is a loose structure in which each actor performs intelligence functions in priority for its own benefit and then may share its work with other EU intelligence entities and decision-making bodies. It is particularly the case for EUROPOL and FRONTEX[10].

Moreover, the community does not have a common intelligence culture, which might hamper efficient cooperation. For instance, INTCEN and EUMS INT approach secrecy as a prerequisite for any intelligence activity and for security broadly speaking, whereas EUROPOL is more concerned about secrecy when it comes to privacy and criminal investigations’ integrity[11].

Furthermore, information obtained by the more than 130 EU diplomatic representations worldwide is inefficiently integrated into the EU’s intelligence process. In fact, the EU doesn’t consider diplomats’ political analyses as inputs for the intelligence process whereas their strategic dimension could help EU intelligence agencies make sense of other pieces of information in their possession. Besides, EU diplomats may be reluctant to cooperate to reinforce the EU’s intelligence system because they may consider that they should be the ones benefiting from intelligence rather than the EU’s intelligence system benefiting from their contributions[12].

II. Is a European Intelligence Agency the solution?

A. Advantages

A European Intelligence Agency would make the EU intelligence community integrated and centralised around a single and comprehensive process. It will thus rationalise the use of EU resources by preventing the duplication and overlap of intelligence activities. Likewise, from the perspective of member States, a European Intelligence Agency would be able to perform open-source information collection and share it with all member States, thus avoiding a situation where they all collect and process the same data through their respective national intelligence process.

Besides, since intelligence from open source can represent up to 90% of all intelligence activities[13], a European Intelligence Agency’s output will contribute to reducing information asymmetry between EU member States and empower those with less experience and resources in the field of intelligence. It will also provide a common comprehensive and neutral appreciation of a given situation, which in the end fosters consensus-building and prevents deadlocks[14].

Moreover, with regards to transnational threats like terrorism, a European Intelligence Agency would facilitate the cross-border collection of information and render their access easier for all member States.

B. Limits and challenges

- Member States won’t relinquish sovereignty

As a matter of fact, members States have divergent views about Jean-Claude Juncker’s idea of “a Europe that protects”[15]: some prefer to preserve member States’ primacy when it comes to defence, security and therefore intelligence, while others advocate for a reinforcement of the prerogatives of EU institutions in these domains. This disagreement boils down to the question of whether the EU should be a supranational or simply an intergovernmental entity. It also raises the question of whether it is possible to have an intelligence agency without a nation-State i.e. without “the sense of common interest, the feeling of deep solidarity that makes mutual trust possible”[16] as pointed out by J-M. Palacios.

- Concerns about the level of secrecy of this new institution

Member States may be reluctant to approve the creation of a European Intelligence Agency as it might expand the number of recipients of sensitive information and increase the risk of leakage[17]. Moreover, the EU has difficulties ensuring secured communications of classified information[18] and there is also the risk that a large and diverse entity like a European Intelligence Agency might be penetrated by foreign intelligence services[19].

- Some practical considerations

Establishing a European Intelligence Agency is still a vague project with many practical questions left unanswered and for which the EU might not yet be able to provide satisfying answers: What will be the cost of creating this new organisation? How long will it take before it catches up with national agencies, and should it even try to replicate the model of national agencies? Should it conduct covert actions? How would its staff be recruited? How would parliamentary and judicial controls be carried out? Will this intelligence agency only have one client, the Council for example, or would it also deal bilaterally with other EU decision-making bodies? Will specialised entities like FRONTEX or EUROPOL have to cease their intelligence activities and potentially merge into the European Intelligence Agency?

III. How to foster intelligence cooperation between member States and better integrate the fragmented EU intelligence community?

A. Promoting a non-integrated and informal cooperation between member States for sharing best practices

The EU’s institutional complexity, variety of stakeholders and collective action problems deter member States from cooperating on intelligence in a formal and integrated way at the EU level[20]. It is also unrealistic to demand them to share highly sensitive information whose acquisition was resource-consuming and whose dissemination might not serve directly their interests. Therefore, EU member States’ intelligence cooperation should be centred around sharing best practices and knowhows via informal groups and networking events.

European intelligence actors would thus gather around the common objective of improving the functioning of their respective intelligence system, without risking compromising State secrets. Moreover, informality preserves a certain degree of secrecy, which reduces member States’ reluctance to cooperate on intelligence matters with their fellow European partners.

This can be done through informal multilateral groups like the Club de Berne, the Counter Terrorism Group, the Budapest Club or the Eurosint Forum. For example, the Eurosint Forum allows European intelligence officers to exchange ideas on digital transformation. The INTCEN also serves as an informal hub for intelligence and military officers to share points of view.

The objective of the EU now should be to densify these informal networks so that member States cooperate more on technical matters and build mutual trust, which might eventually lead to cooperation on more sensitive subjects with the potential sharing of substantive information.

B. Setting up a fusion centre to better coordinate the EU’s intelligence community and facilitate top EU authorities’ decision-making process

As briefly mentioned by Ursula von der Leyen in her 2021-State of the Nation speech, EU authorities’ decision-making process would be facilitated if information they receive was not fragmented and allowed them to “have the full picture”[21]. An intelligence fusion-centre could be a solution as it would pool all information provided by the various intelligence actors as well as by EU delegations and then make sense of it all to communicate it in a clear and comprehensive way to top EU decision-makers. In fact, the latter would receive intelligence output and communicate their request to the intelligence community through the same interlocutor. The fusion centre could also spread information received from a given member of the intelligence community to the other members when it is relevant and according to the “need-to-know” principle.

The Single Intelligence Analysis Capacity (SIAC) could play this role as it already more or less does so by combining intelligence output from INTCEN and EUMS INT[22].

The efficiency and reliability of this system would be improved by ensuring an automatic and constant inflow of intelligence products from intelligence actors to the SIAC/fusion-centre. This would leave no discretion to intelligence actors as to what information they share with the fusion centre. It would also prevent a loss of responsiveness of the EU intelligence community to EU political authorities that could be caused by the establishment of a new intermediary bureaucratic structure. This system would also contribute to developing a common intelligence culture and standardise communication methods, which would reinforce the EU intelligence community’s interoperability and level of secrecy.

Conclusion/Executive summary

The EU’s fragmented and heterogenous intelligence community is too reliant on member States that are not cooperative enough. Establishing a European Intelligence Agency would be an ideal solution that would however face practical difficulties as well as member States’ concerns about sovereignty and secrecy. The EU should focus on what it can realistically do to foster member States’ cooperation and better coordinate its intelligence community: developing informal non-integrated networks for technical cooperation and using an intelligence fusion-centre to facilitate top EU authorities’ decision-making process.

[1] Borrell, Josep. A Strategic Compass for Security and Defence. EEAS, March 2022, p.4.

[2] Palacios, José-Miguel. “EU-Intelligence: On the road to a European Intelligence Agency?” in Dietrich and Sule, Intelligence Law and Policies in Europe, Oxford 2019, p.207.

[3] EU Intelligence and Situation Centre

[4] EU Military Staff’s Intelligence division

[5] European External Action Service

[6] European Union Satellite Centre

[7] Sánchez Amor, Nacho. Why the EU Need Access to First-Hand Intelligence Information. Agence Europe, Brussels, 17 Nov. 2022.

[8] Nielsen, Nikolaj. No New Mandate for EU Intelligence Centre. EUobserver, Brussels, 6 Feb. 2015.

[9] Müller-Wille, Björn. For Our Eyes Only: Shaping an Intelligence Community Within the EU. European Union Institute for Security Studies, Occasional Papers n°50, Paris, January 2004.

[10] Palacios (2019: 213).

[11] Palacios (2019: 219).

[12] Palacios (2019 : 232).

[13] Ünver, H. Akın. Digital Open Source Intelligence and International Security: A Primer. Centre for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies, 2018.

[14] Palacios (2019: 210).

[15] Juncker, Jean-Claude. State of the Union Address 2016: Towards a Better Europe – a Europe That Protects, Empowers and Defends. European Commission, Strasbourg, 14 Sept. 2016.

[16] Palacios (2019: 228).

[17] Novotný, Vít. A European Intelligence Agency: The Cons Outweigh the Pros. Vocal Europe, 6 Apr. 2016.

[18] Palacios (2019: 212).

[19] Novotný (2016).

[20] Palacios (2019: 220).

[21] Von der Leyen, Ursula. 2021 State of the Union Address by President von Der Leyen. European Commission, Strasbourg, 15 Sept. 2021.

[22] Joint answer given by High Representative/Vice-President Ashton on behalf of the Commission to Questions N° E-006018/12 and E-006020/12. European Parliament, Parliamentary Question, August 2012.

0 Comments