West Africa, a Hotbed of NARCOTERRORISM

This article is mainly a translation of Tigrane Yegavian’s article “L’Afrique de l’Ouest, ventre mou du narcoterrorisme” published in the magazine Conflits in July 2021.

What you want to understand… 🤔

- What is narcoterrorism?

- How do South-American cartels and Italian mafias collaborate with West-African terrorist groups?

- How are governments fighting both drug trafficking and terrorism?

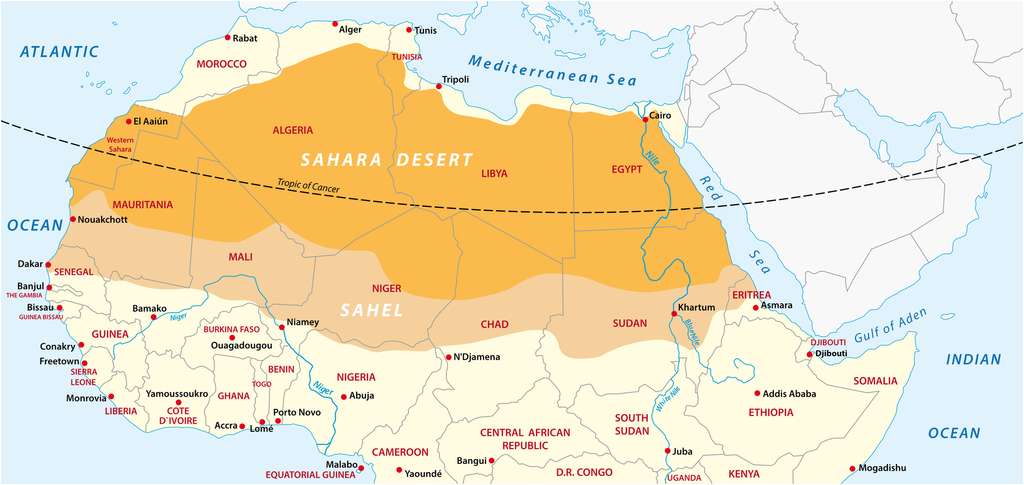

In the space of a few years, West Africa has become a major transit route for South American drugs destined for European markets. Even though South American cartels have seeped into the Sahel, sometimes even linking up with jihadists, African cartels have also emerged.

In November 2009, images of a crashed Boeing 727 in the north of Gao in Mali revealed the extent of a previously unknown phenomenon. The plane, which had come from Venezuela near the Colombian border, was carrying several tonnes of cocaine. A new threat was emerging from the convergence of extremist movements in the Sahel and drug traffickers in South America.

Narcoterrorism refers to the convergence of drug-trafficking and terrorist activities. Either terrorism is used to protect and expand criminal networks centred around drug, or drug-trafficking is used to finance terrorist organisations with broader religious and political goals.

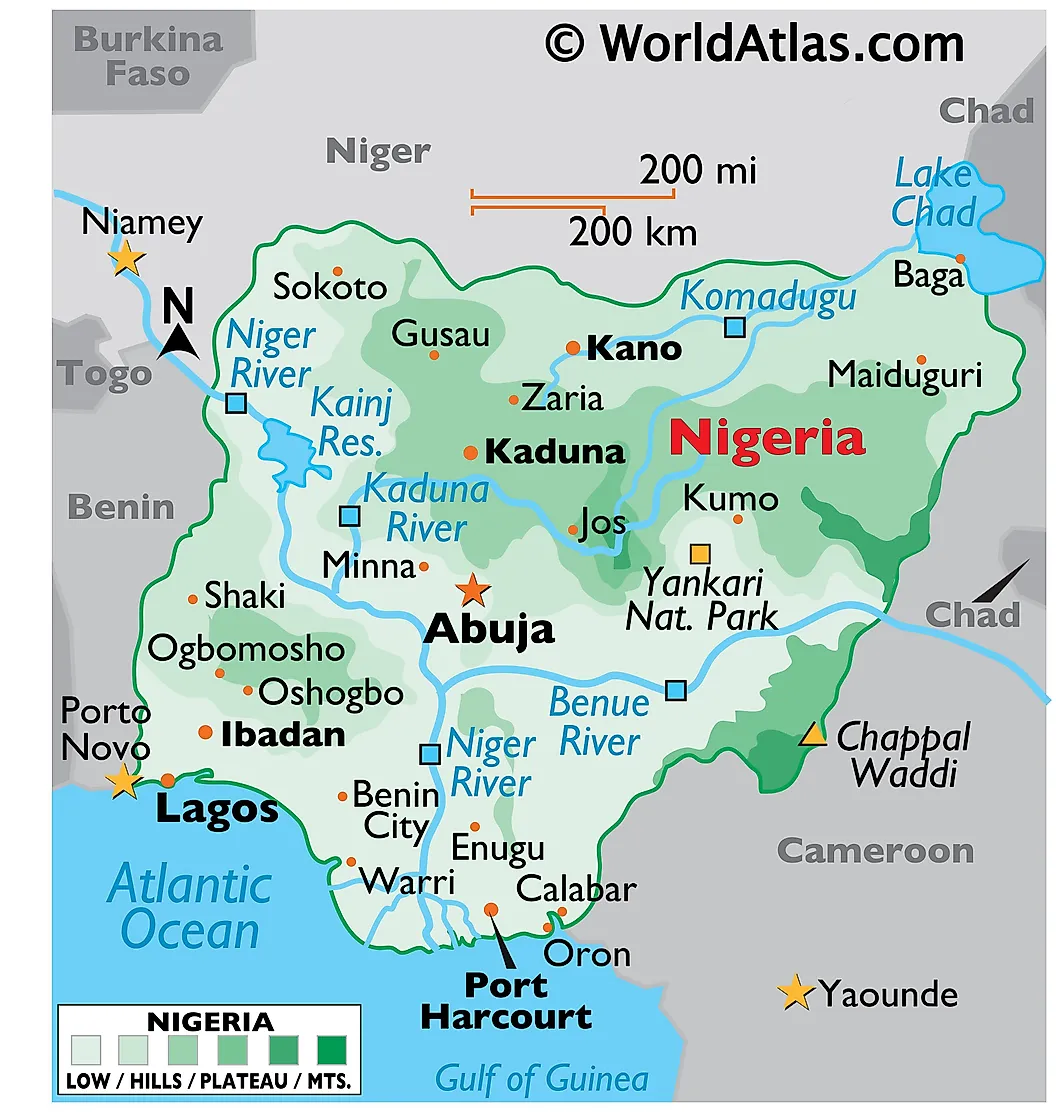

Drug trafficking in the Sahel was on the rise as early as the 1960s when Nigeria was a hub for drug that was travelling from Lebanon to the United States. Subsequently, Nigerian and Ghanaian traffickers focused mainly on cannabis destined for Europe. With the explosion of drug trafficking in the 1990s, Latin American drug traffickers took advantage of the African continent which represented a poorly controlled transit highway. With its porous borders, its ideal location close to Europe and its fragile states where corruption reigns, West Africa has become a hub par excellence for drug trafficking. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates, the trade is booming. Indeed, the market value of cocaine transiting through West Africa each year was estimated at $1.25 billion in 2013.

I. Drug traffickers’ preferred transit area for cocaine

In the past, South American drug traffickers traditionally carried drugs through Caribbean Islands and the Azores to get to Europe. They now favour West Africa that allows them to both avoid US authorities’ controls off the Caribbean and take advantage of the political instability, societal neglect and corruption that plague several Gulf of Guinea and West African states. A 2015 UNODC report indicates that around 18 tonnes of cocaine transit through West Africa each year on their way to Europe by air, sea or land. Arriving by boat, the merchandise is unloaded on the coasts of Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde and Senegal to be transported by land to Togo. From there, planes take off along several routes passing through Ghana or Benin and then through Burkina Faso and Mali.

Listed as a narco-state by the UNODC, Guinea-Bissau has a unique maritime frontage thanks to the protected archipelago of the Bijagos (hundreds of deserted islands scattered around). Moreover, during the war of independence between 1963 and 1974, the Portuguese built makeshift airstrips on these islands. It’s one of the reasons why Colombian traffickers took up residence there in the years 2004-2007. They flourished and infiltrated the political milieu as well as the senior civil service. For instance, in March 2009, the President of the Republic of Guinea Bissau, Joao Bernardo de Vieira, was murdered. He was suspected of being involved in drug trafficking. Six years later, a report by International Narcotics Control described Guinea-Bissau as a transit centre for cocaine trafficking, stating that Guinea-Bissau’s political system was “under the influence of drug traffickers”. In 2013, the Institute for Security Studies estimated that 13% of the cocaine shipped to Europe transited through Guinea-Bissau. The arrest the same year of the Navy Chief of Staff, José Americo Na Tchuto, by American agents of the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) dealt a severe blow to trafficking. We can add that, in 2018, a senior UN official in Bissau estimated that “no less than 30 tons” of cocaine entered Guinea-Bissau each year.

II. Nigeria as a command and control centre for drug trafficking

There are many ports in the Gulf of Guinea where cocaine enters, but also where synthetic drugs are exported to Western Europe and the Far East. Albeit Ghana is a major hub for this kind of trade, Nigeria is the most important. The most populous African country has become the epicentre of drug trafficking from Latin America as well as from Afghanistan and Pakistan. According to Transparency International, in 2020 Nigeria was the 25th most corrupt country on the planet out of 168 countries studied, overtaken by Guinea-Bissau (19th). Some Nigerian criminal organisations, such as Black Axe, have gained a structured global presence and operate through Nigerian transnational networks. The discovery in March 2016 of a methamphetamine “super lab”, built with Mexican help, in the city of Asaba with a production capacity of 4 tons/week revealed the professionalism of Nigerian drug traffickers trained by their Latin American colleagues.

(below: Nigerian authorities arrested 8 men including 4 Mexicans in the “super lab”)

However, Nigerian mafias have gradually gained control over cocaine trafficking at the expense of Bolivians and Colombians drug traffickers expatriated in West Africa. Besides, Nigerians have made deals with Pakistanis and Afghans so that the sub-region can become an arrival point for Asian heroin that will be sold in Europe.

III. Mafia Networks and Jihadist Collusion

Drugs generate colossal revenues thus offering dangerous corrupting powers. Officials and politicians at all levels can be targeted by bribery, from customs officers to judges and even ministers. In this respect, drug traffickers are reproducing in Africa a pattern that has proved successful in Italy and Mexico.

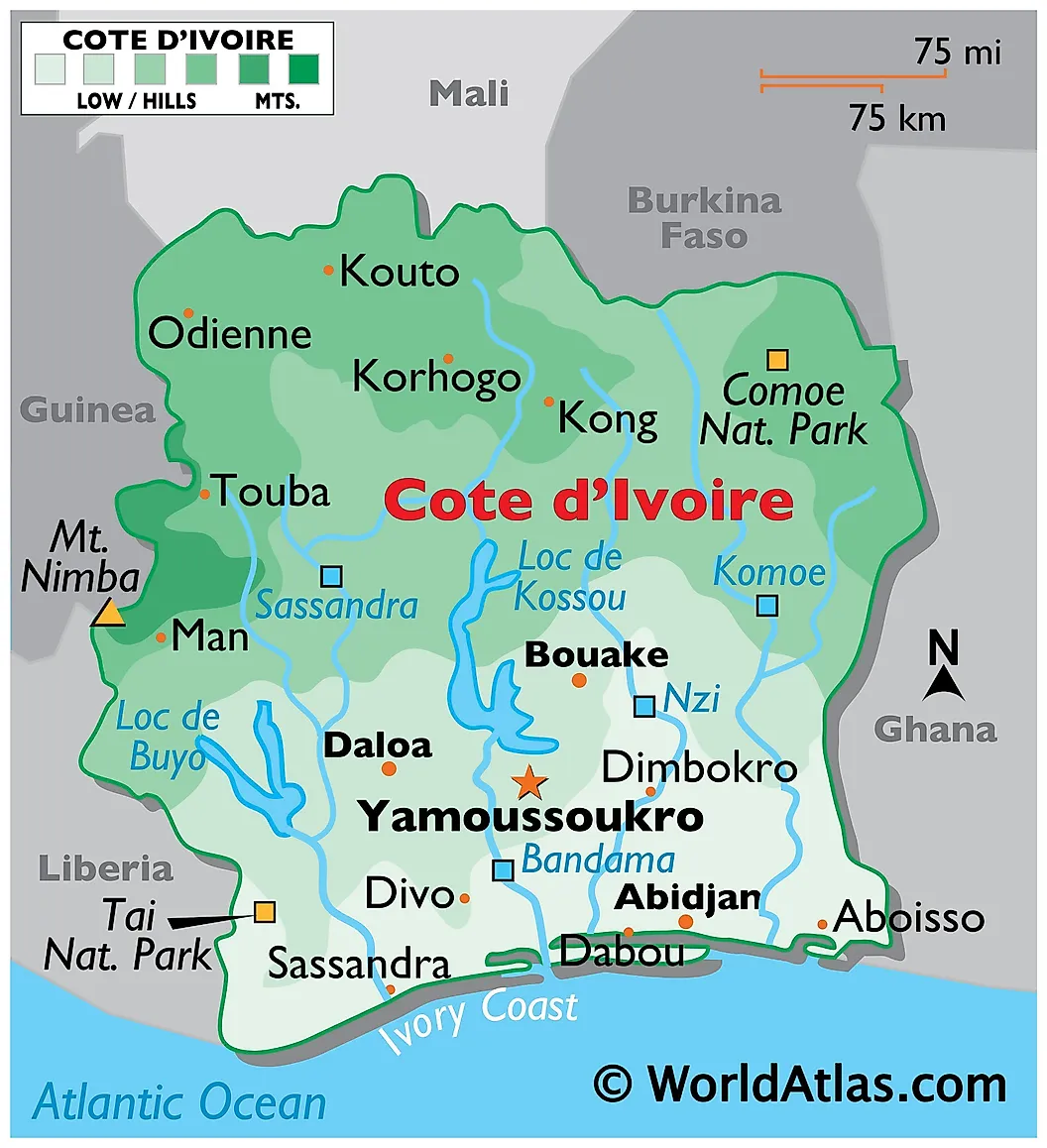

The Italian Calabrian mafia, the ‘Ndrangheta, is present in several African countries like Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, South Africa and the Maghreb. The Cosa Nostra is also active in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Namibia, DRC, Angola and Ghana. The Camorra from Naples is expending its activities (prostitution, drugs, human trafficking…) in West Africa and in fragile countries such as the Central African Republic. Founded in 1989, the Mexican Sinaloa cartel is also heavily involved in cocaine trafficking in West Africa. Many other Mexican cartels carry out illegal activities in the region by cooperating with local criminal groups and more importantly jihadists…

Despite the fierce competition between violent Salafist groups in the Sahel, fundamentalists of all stripes agree that drug trafficking can be halal (“permissible”) when it is intended to poison miscreants (the non-Muslim world dar al-harb) and ‘bad Muslims’ who stray from the path of violent jihad. That’s why jihadist groups do not mind collaborating with drug traffickers, provided they keep control of trans-Sahelian and trans-Saharan routes through which drugs and arms are smuggled to the Maghreb and Europe.

While jihadists use illicit substances in abundance to control their fear of combat, they have seen drug trafficking as a significant source of income. However, unlike the Afghan Taliban, who control and export poppy crops, jihadists only protect the transport of Latin American cocaine through the Sahel region. Nigerian jihadists have in fact established contacts with drug traffickers in the port cities of Calabar and Port Harcourt as well as in Côte d’Ivoire in San Pedro and Abidjan.

Operating like a normal mafia network, Boko Haram pays off people in charge of port infrastructures, not only with money but also with prostitutes. According to Alain Rodier, director of research at the French Centre for Intelligence Research, Nigerian jihadists film those they bribe with prostitutes in case they start having second thoughts and want to stop working for them.

Boko Haram’s activities also include the transit of cocaine and heroin from South Africa or Tanzania (the main point of entry for Afghan heroin and the Golden Triangle) through the Sahel to embarkation points in Libya and other countries in the Maghreb.

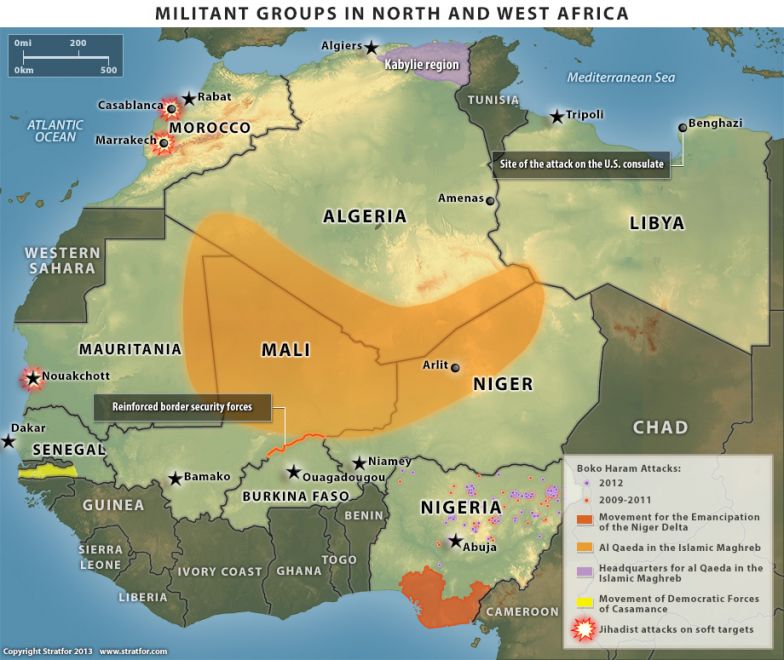

Boko Haram collaborates occasionally with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) to help with the transit of drug in the region even though it has pledged allegiance to Daesh. However, in Libya, AQIM is not in capacity yet to export drugs from its stronghold in Sirte. The main European maritime destinations are believed to be Great Britain and Italy, but entry points are extremely diverse.

From what we just said, we can draw a parallel between the Nigerian group Boko Haram and narcoterrorist movements that are rampant in Latin America, such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Several Western intelligence services have intercepted communications between Boko Haram and Latin American cartels, but also with the Lebanese Hezbollah, a Shiite movement supposedly fought by Salafist jihadists.

IV. Mali, Another Epicentre of Narcoterrorism

Since the early 2000s, traffickers have moved large shipments of South American cocaine through North Mali. They use criminal networks that traditionally focused on trafficking cannabis resin and contraband cigarettes. AQIM took advantage of this situation and has thus earned tens of millions of dollars in ransom money, banditry, smuggling and protection blackmail. While there is no consensus on the figures of this juicy trade, most agree that cocaine trafficking through West Africa reached its peak between 2008 and 2009 with estimates of around 47 tons in 2007-2008. Nonetheless, this quantity is thought to have decreased: only half of it was trafficked in 2017.

Taking advantage of the security vacuum caused by rebellions in the Sahel region and the disastrous consequences of Gaddafi regime’s fall in Libya (e.g. spread of weapons in the region), jihadism has flourished in Western and Central Africa. If AQIM jihadists are not directly involved in trafficking, they are often called on to ensure the protection of convoys, secure airstrips, supply fuel or even collect transit fees.

Before the French intervention in 2013, there were three main jihadist formations operating in northern Mali: AQIM, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa, and Ansar Dine. Financed by Islamic NGOs and private donors from the Gulf, Ansar Dine has diverse sources of funding such as paid ransoms, cigarette trafficking, narcotics trafficking…. Drug trafficking and money laundering in the region has taken on a new dimension as links have intensified between narco-traffickers and terrorist groups in the Sahel. In parallel, connections have been reinforced between jihadist narco-terrorists and European mafia groups. This is particularly true for the Camorra whose expertise in trafficking false documents has benefited jihadist movements.

We can now notice the progressive formation of hybrid groups inspired by the FARC model: political or religious ideology can be very pragmatically combined with organised crime and narcoterrorism.

V. What is the African Response?

The reaction from African states came rather late. Under the impetus of former UN Secretary General Koffi Annan, a West African Commission on Governance, Security and Development in the Context of the Fight against Drug Trafficking was set up in 2013. Five years earlier, a coordinating body for the fight against trafficking in the Atlantic Ocean was created: the Maritime Analysis and Operations Centre – Narcotics (MAOC-N). Based in Lisbon, this international agency’s main objective is to suppress illicit drug trafficking by sea and air in the Atlantic. Increasingly large maritime and intelligence resources are pooled to conduct joint operations with African units. The aim is to train local anti-drug services. This is a challenging task given trafficker’s adaptability to surveillance and repression methods.

Some countries like Nigeria are currently facing an explosion of their local market as they are sourcing cocaine from European market surplus. This phenomenon is aggravated by large-scale local manufactures of methamphetamine in Nigeria and Guinea Conakry. They supply local markets as well as Asian countries.

Criminal Caribbean organisations have replicated their structures in West Africa by using their diaspora and formal economic activities as their entry points. Consequently, real economies are being weakened by tax evasion and embezzlement at the expense of education, health and infrastructure investments. As long as instability and anarchy persist in the grey areas of West Africa, drug trafficking has a bright future ahead of it.

5 Comments

Al-Qaeda and Daesh in Africa - geopol-trotters · 30 January 2023 at 7:07 am

[…] trafficking routes from the Ivory […]

[Part 2] The War in Afghanistan (2001-2021) - geopol-trotters · 26 November 2022 at 7:12 pm

[…] Taliban’s religious objectives were intertwined with mafia objectives like trafficking opium. In fact, getting involved in drug trafficking allowed them to both finance their war and gain […]

The French Intervention in Mali since 2013 - geopol-trotters · 24 September 2022 at 2:46 pm

[…] Moreover, we can assume that illegal traffics would flourish in the Sahel after a take-over by jihadists. Traffickers would use the vast and non-monitored spaces offered by the Sahara to smuggle drugs to Europe through the Maghreb for instance. […]

Wars in Afghanistan since 1979 and the recent US failure - geopol-trotters · 5 October 2021 at 11:43 am

[…] were financed by Pakistani funds but they are also involved in criminal networks. Indeed they traffic drugs such as poppy crops used to produce […]

Daesh’s Statehood and Caliphate - geopol-trotters · 30 August 2021 at 2:33 pm

[…] place. The risk for IS was to be victim of the “Insurgency Resource Curse” and to turn into a criminal network which might have interfered with its plans to draw support from local […]