The end of UN PEACE MISSIONS ?

Your 5-minute weekly dose of geopolitics in a straight-to-the-point and illustrated format. Enjoy!

I) UN peace operations have always been criticised for their inefficiency

A. UN peace operations often fail to reach their goals

Traditionally, UN peacekeeping missions serve an interposition role in the context of interstate wars following a ceasefire. They usually focus primarily on the security dimension of crises and at times address their humanitarian consequences.

Their operational doctrine, laid out in the 2008 Capstone Doctrine, rests on three principles:

- Consent of the parties

- Impartiality (equal treatment without discrimination)

- Non-use of force except in self-defence and defence of the mandate

The example of UNMISS in South Sudan illustrates the inadequacy. As of 2023, this was the largest UN peacekeeping mission, with around 18,000 personnel. Yet, it has struggled to contain widespread violence and facilitate development. The mission has not prevented the continued fragmentation of the state or ethnic clashes.

The failure of UN missions to prevent conflicts and violence is nothing new. The 1995 Srebrenica massacre, during which 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were killed, occurred despite the UNPROFOR mission’s presence on the ground. This event epitomises the limits of a mandate based on restraint and neutrality in the face of genocidal violence.

B. UN missions are also increasingly rejected by local populations

Beyond structural weaknesses, traditional peacekeeping missions face growing hostility from the very populations they are supposed to protect. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the MONUSCO has been accused of passivity in the face of mass killings in Eastern provinces. Violent protests erupted in 2022 and 2023, demanding the mission’s departure. In response, the MONUSCO launched a disengagement process, starting with its withdrawal from South Kivu in June 2024.

A similar scenario unfolded in Mali, where Asimi Goita’s military junta, criticising MINUSMA’s inefficiency and viewing it as a threat to national sovereignty, requested its departure. The withdrawal of MINUSMA was completed in December 2023, marking a new low point in UN peacekeeping credibility in the Sahel.

II) Despite attempts to increase their efficiency, UN peace operations remain subject to major criticisms

A. Towards a more comprehensive format addressing both pre- and post-conflict needs

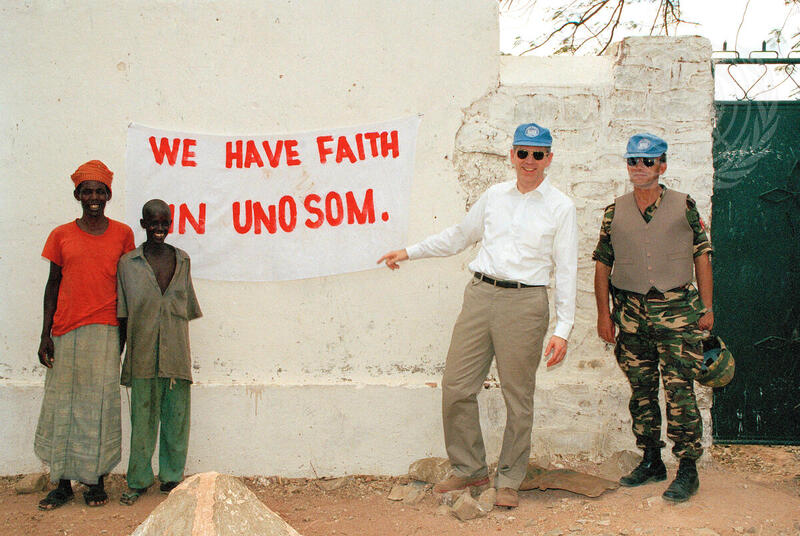

While 1st-generation peace operations (1948-1980s) focused on peace-keeping and interposition, the 2nd generation of peace operations (1990s-2000s) focused on peace-enforcement. In other words, these 2nd-generation operations sought to uphold the conditions for peace and combined civilian tasks, e.g. humanitarian aid, with security enforcement, e.g. restoring order and disarming rebel fighters. They aimed at supporting State capacities, in particular when faced with failed States like in Somalia in 1992 when the UNOSOM was launched. This evolution aligns with the concept of “human security,” introduced in the 1994 UNDP Human Development Report, which focuses on “freedom from want and from fear”.

The 3rd generation of peace operations (since the 2010s) embraces the concept of peace-building. In fact, they tackle the economic, social, governance, humanitarian, educational, and security dimensions of crises. They aim to intervene both upstream (prevention) and downstream (reconstruction) of conflict cycles, adopting a holistic and long-term approach.

B. Yet this new model is far from solving all the problems

The main criticisms towards this new format of UN peace operations include:

- The cost → in 2023/2024, the yearly cost of the MONUSCU in the DRC exceeded $1 billion

- The mandate → objectives are too vague and ambitious, making it difficult to set measurable goals or assess success

- The number of actors involved → due to the growing diversity of sectors covered by their mandate, UN peace operations have difficulties coordinating all UN agencies, NGOs, regional organisations, and donors. Moreover, rival agendas and competition for resources often undermine coherence and effectiveness on the ground.

Finally, from the perspective of host governments and populations, these expansive missions can feel like foreign interference. The perceived erosion of sovereignty and the imposition of external models of governance fuel local resentment, jeopardising long-term legitimacy and cooperation.

Conclusion

It is worth mentioning that, aware of the multiple criticisms mentioned above, the UN has initiated changes with regards to its peace operations.

Indeed, in July 2023, the UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, presented a “New Agenda for Peace” that outlined the new format of UN peace operations : less ambitious and more realistic.

Likewise, still in 2023, the UN Security Council (UNSC) authorised, as per Chapter 7 of the UN Charter, the Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission in Haiti. This mission consists solely of non-UN police forces sent by volunteer States, that also ensure the overall financing, to support Haitian police forces in their action against gang violence. However, current budget shortcomings and logistical issues risk preventing this innovative peace operation format from demonstrating its full potential.

Peace operations will probably also become more regionalised. As a matter of fact, resolution 2719 of the UNSC (2023) established a stable financing framework for peace operations led by the African Union. The costs of these operations would be covered at 75% by the UN and at 25% by the AU and the international community. This type of operation might be launched for the first time in Somalia in order to avoid a security vacuum after the departure of the African Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS), even though the latter will probably first be replaced by the AU Support and Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM).

1 Comment

CHINA – NORTH KOREA, an unswerving alliance? – geopol-trotters · 18 October 2025 at 3:06 pm

[…] in 2018, in an effort to improve its public image, China began applying UN Security Council international sanctions introduced in 2005-2006 against North-Korea. Beijing has also openly called […]