Conflicts in Yugoslavia in the 1990s

What you want to understand… 🤔

- What is the History of Yugoslavia since the end of the First World War?

- Who was Tito and what did he do during his ruling period (1946-1980)?

- Why can’t Serbs and Croats stand each other?

- What were the different wars that took place in the 1990s and that brought about the end of Yugoslavia?

- What role did the UN and NATO play in these wars?

- How were the crimes perpetrated during Yugoslav wars judged?

I. Background Information

A. The Interwar Period (1918-1939)

At the end of World War I, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was created. Peter I of Serbia became its first ruler. As a matter of fact, the Serbs (Orthodox Christians) dominated the kingdom that was also inhabited by Croats and Slovenes (Catholic Christians) as well as Bosnians (Muslims).

Without going too much into details, it is worth bearing in mind that Serbs and Croats cannot stand each other, relations are still troubled nowadays. Many factors account for this like religious differences or differences of treatment by those who ruled the region over the centuries.

In 1929, the kingdom changed its name into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia means “Land of the South Slavs” in Serbo-Croatian.

B. Yugoslavia in World War II

In March 1941, Prince Paul’s government signed a Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. As a result, some military officers launched a coup and managed to replace Prince Paul by King Peter II, 17 years old at the time. However, German and Italian forces invaded Yugoslavia few days later in April 1941.

The Croat fascist and ultranationalist militia Ustaše helped Axis powers gain control over the region. Its founder, Ante Pavelic, became the ruler of the Independent State of Croatia.

The Ustaše persecuted, deported and killed Gypsies, Jews and Serbs. They organised forced conversions to Catholicism but they tolerated Islam, the religion of Bosnians who were seen as Muslim Croats.

Nevertheless, several movements of resistance emerged in Yugoslavia. For instance, in Serbia, Orthodox nationalists named the Chetnik resisted Axis invaders and their Croatian collaborators under the leadership of Dragoljub Mihailovic. His plan was to avoid large-scale confrontations and wait for the Allies to invade the region.

Besides, in Croatia, Josip Broz Tito led the Croat communist resistance: the Partisans. Ideological and strategic differences led the Chetnik (Serbs) and the Partisans (Croats) to fight each other. Eventually, Tito got the upper hand, gained popular support, obtained the Allies’ help and along with the Red Army managed to expel Axis forces from Yugoslavia in October 1944.

C. Yugoslavia during the Cold War

1. Rebuilding Yugoslavia on Communist bases

In 1945, the Partisans abolished the monarchy. The next year, they established a communist regime and Yugoslavia became the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia and then the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1963.

6 states composed this federal republic:

- Slovenia

- Croatia

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Serbia

- Montenegro

- Macedonia

Moreover, there were 2 autonomous Serbian provinces:

- Kosovo

- Voljvodina

Due to disagreements with Stalin, Tito parted and decided to adopt a communist approach centred around Yugoslav-specific issues. For instance, Tito’s government implemented some reforms of market socialism (something that was also seen in China with Deng Xiaoping in 1978). That’s why he took part in the non-alignment movement that started with the 1955 Bandung Conference. Furthermore, Tito had close ties with influential leaders like Nehru in India and Nasser in Egypt.

Tito promoted a pan-Yugoslav ideology. Indeed, he endeavoured to unify Slavic people regardless of whether they were Croats, Bosnian, Serbs, Slovenians, Montenegrins or Macedonians. As a result, nationalist movements were suppressed which actually anchored their position as the alternative to communism.

2. The slow rise of nationalist movements

Besides, there were still ethnic tensions: Serbs still resented Croats and Bosnians for persecuting them during WWII. To add insult to injury, Croatia and Slovenia were the richest states of Yugoslavia and they didn’t want to pay for poorer states like Serbia. Furthermore, economic disparities increased in the 1970s due to oil shocks in 1973 (Kippur War) and 1979 (Iranian Revolution). Yugoslavia then split into 2 camps:

- Croatia + Slovenia = liberalism + decentralisation

- Serbia = conservatism + nationalism + centralisation

In 1974, Tito established a new constitution. Among the several changes it brought, we can mention that the two Serbian autonomous provinces Kosovo and Voljvodina got more independence. They even got a de facto veto power in the Serbian Parliament which infuriated Serbian nationalists. Moreover, the Constitution declared the 6 states of Yugoslavia independent and sovereign. Additionally, the Constitution provided for the possibility for states to secede from the Yugoslav federation. Nonetheless, all states and provinces of the federation had to express their consent before making any alteration to Yugoslavia’s borders. We can also note that this 1974 Constitution established Tito as the President of Yugoslavia for life.

When Tito died in 1980, communism ran out of steam in Yugoslavia and nationalist movements gained more influence across the federation.

In Croatia, Franjo Tudjman led a movement of nationalist separatists. He obtained support from mafia groups and people nostalgic of the Ustaše period. In May 1990, the first free legislative elections took place in Croatia and Tudjman became President of Croatia.

As for Serbia, Slobodan Milošević led a nationalist, socialist and populist/anti-bureaucracy movement. In May 1989, he was elected President of Serbia and then progressively managed to reduce the autonomy of Kosovo and Vojvodina. At the time, Serbia was the largest and most populous state in Yugoslavia. Furthermore, and it is very important for understanding Serbian actions in the 1990s, Milošević was a proponent of pan-Serbian ideas. In fact, he wished to create a Greater Serbia in which all Serbs would dwell. His plan entailed taking control of all territories ruled or populated by Serbs, including those in neighbouring countries.

II. The Beginning of the End for Yugoslavia

In May and June 1991, Croatia and Slovenia declared their independence. In December 1991, it was the turn of Macedonia to secede from Yugoslavia.

While Macedonia managed to get out of the Federation of Yugoslavia peacefully and through negotiations, Croatia and Slovenia had to go through war.

In June 1991, Slovenian forces fought against the Yugoslav People’s Army in what is called the Ten-Day War. The conflict was limited to some skirmishes and there were few casualties. Eventually, through negotiations, Slovenia got its independence and international recognition from the European Community and the United Nations in 1992.

For Croatia however, the path to independence was longer and more violent as we shall see now.

III. War in Croatia (1991-1995)

A. Context

Since his election in May 1990, Tudjman implemented several nationalist policies aiming at eventually secede from Yugoslavia. For instance, he reinstated the traditional Croatian flag and his government made several propositions to modify the Constitution in favour of Croats and sometimes at the expenses of Serbs.

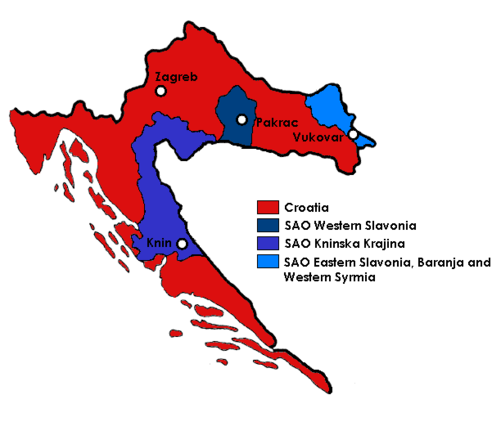

That’s why, as soon as December 1990, Serbs-dominated regions (in red on the following map) started declaring their independence from Croatia. Few months later, it became the Republic of Serbian Krajina, a self-proclaimed state without international recognition.

Milošević, the Serbian leader, was strongly opposed to Croatia’s declaration of independence in May 1991. Croatia both was a rich region and it hosted an important Serbian minority in its South, which from Milošević’s pan-Serbian perspective implied that it was unacceptable for Croatia to leave Yugoslavia.

B. The Conflict

Serbia then openly supported Serbian rebellions in Croatia. Furthermore, given that the Yugoslav People’s Army was made up of a majority of Serb and Montenegrin soldiers, Milošević had no difficulties using it to help Serbs in Croatia fight the Croatian government.

Therefore, as early as July 1991, tens of thousands of soldiers of the Yugoslav People’s Army entered Croatia starting an all-out war. Croat forces couldn’t resist for long and Yugoslav forces advanced rapidly westwards.

During their progression, the Yugoslav People’s Army along with Serbian rebels committed several massacres. The largest one took place on November 20, 1991, in the Ovčara farm located at the south of Vukovar. As a matter of fact, between 200 and 300 prisoners of war (mainly Croats) and civilians were beaten up, shot and buried in a mass grave by Serb paramilitaries.

The Sarajevo Agreement (aka the Vance Plan) of January 1992, which was not a final settlement of the conflict, involved both a deployment of UN forces and a withdrawal of Yugoslav forces from Croatia. The goal was to stop hostilities and allow negotiations to proceed. UN forces were stationed in what was called UN Protected Areas (UNPAs). The borders of these areas roughly consists of those of the Republic of Serbian Krajina, the self-proclaimed state, where Croatian Serbs lived.

It is worth noting that when the Yugoslav People’s Army withdrew from Croatia, it left most of its equipment to Serbian rebels.

Despite the Sarajevo Agreement, Croats and Croatian Serbs still attacked each other between 1992 and 1995 though only sporadically.

C. The End of the War

In 1995, Croatia launched two major operations: Operation Flash and Operation Storm. As a result of these offensives, Croatia regained control over most of the territories occupied by Serbian rebels. The Serbian Autonomous Oblast of Western Slavonia (dark blue area on the map below) was not attacked and it fell under UN administration until 1998 when it was given back to Croatia.

We can say that Croatia came out victorious of this war: it gained independence and its frontiers were preserved. Nevertheless, the war left the Croatian economy in shambles, killed around 20,000 people and displaced hundreds of thousands of refugees, both Croats and Serbs.

Why didn’t UN forces intervene to prevent Croatian attacks?

For those of you who may wonder why UN blue helmets didn’t intervene to prevent fighting betweent Croats and Serbian rebels in UNPAs during Operations Flash and Storm, here’s the answer.

UN peacekeepers can only resort to force in instances of self-defence. Their mission is first and foremost to promote political, not military, solutions to conflicts.

We should also bear in mind that blue helmets are first at the service of their own country and then at the service of the United Nations. As they represent their country on theatres of operations, they may refrain from directly taking part in combats.

If you want more information on UN peacekeeping operations and the role of their military personnel, I advise you to visit the UN website.

IV. War in Bosnia (1992-1995)

A. Context

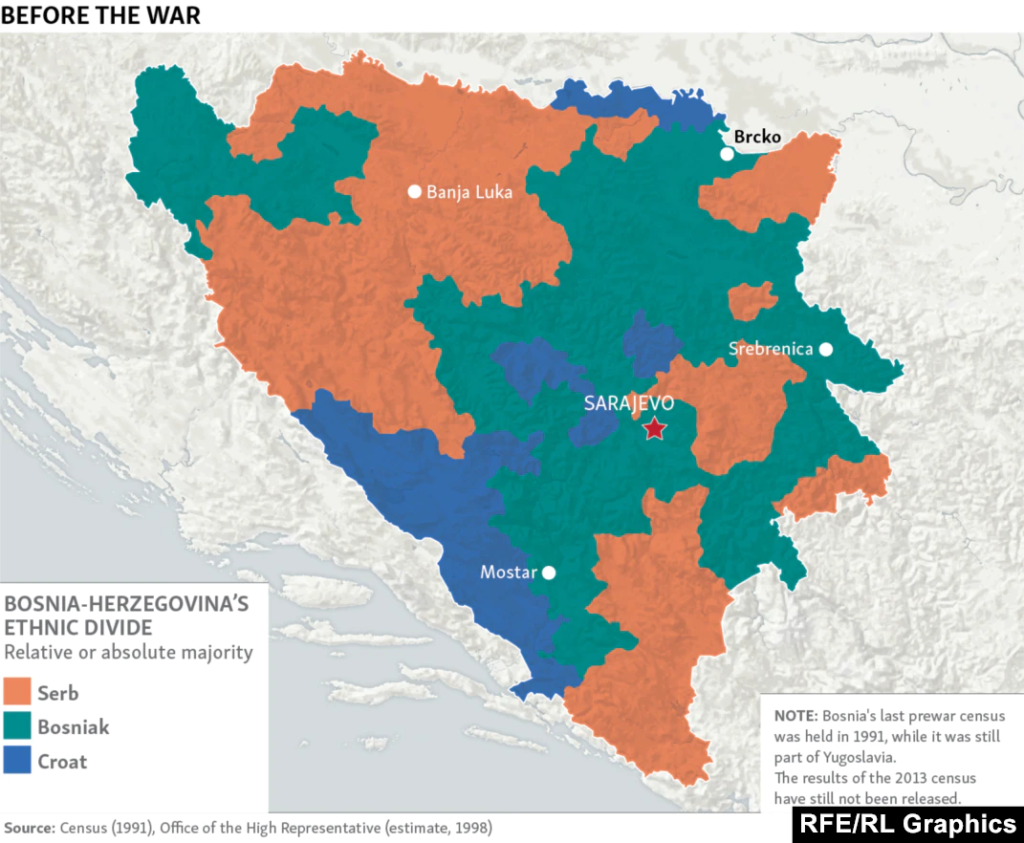

Before starting, let’s see what was the ethnic distribution in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1991. As you can notice each ethnic group was scattered across the country. Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks) represented 44% of the whole population, it was 31% for Bosnian Serbs and 17% for Bosnian Croats.

In November 1991, Bosnian Croats established the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia (roughly the blue region), an unrecognized and self-proclaimed proto-state (i.e. state-like entity) whose ultimate purpose was to merge with Croatia.

Bosnian Serbs did something similar in January 1992 with the Republika Srpska that basically encompassed the red areas on the above map. The leader of this entity was the ultra-nationalist Radovan Karadžić.

B. The Conflict

In April 1992, Bosnia declared its independence from Yugoslavia. From Milošević’s pan-Serbian perspective, and given the important Bosnian-Serbian community, Bosnia couldn’t leave the Yugoslav Federation.

That’s why, under the leadership of General Ratko Mladić, Serbian forces launched several attacks against Bosniak-occupied cities. For instance, the city of Sarajevo underwent a siege of almost 4 years (April 1992 – February 1996). Its inhabitants were victims of daily shelling and sniper attacks.

Within few weeks, Serbian forces had conquered roughly 2/3 of Bosnia.

In parallel, Bosnian Serbs undertook an ethnic cleansing of Bosnia, targeting all non-Serbs, though Bosnian Muslims were the main victims. The objective of Radovan Karadžić was to make Serb-occupied regions of Bosnia (i.e. the Republic Srpska) clear of any other ethnic group.

Among the many massacres that occurred during the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s, the largest one was perpetrated by Bosnian Serbs in Srebrenica in July 1995: they killed more than 7,000 Bosnian men and boys. Even though the UN designated the area around Srebrenica as a “safe area” under its protection, UN blue helmets couldn’t prevent Bosnian Serbs from seizing the city and subsequently killing its inhabitants.

As for Bosnian Croats, they not only fought Bosnian-Serbs but also Bosniaks who rejected the idea of an autonomous and sovereign Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia within its borders. Nevertheless, the Washington Agreement of 1994 brought peace between these two actors.

C. The End of the War

Bosnia and Croatia then decided to join forces and launched Operation Mistral in September 1995 to repel Bosnian Serbs. Along with NATO actions, which started in February 1994 against Serbian forces though with mixed results, Bosniaks and Croats managed to force Bosnian Serbs to sit at the negotiation table.

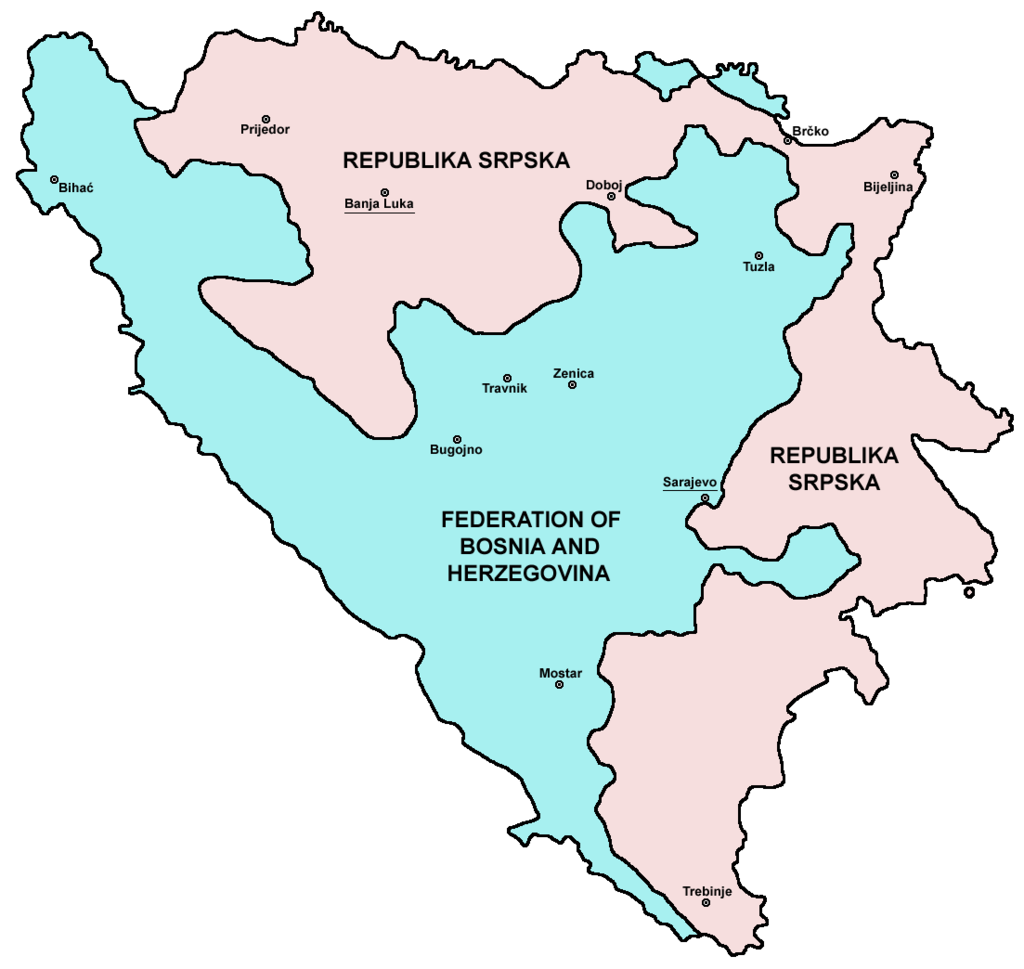

In December 1995, the Dayton Agreement established peace in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The latter became an independent and sovereign state made up of two regions: the Serb-dominated Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina where most Bosniaks and Bosnian-Croats lived. This divide within Bosnia still exists today.

V. War in Kosovo (1998-1999)

A. Context

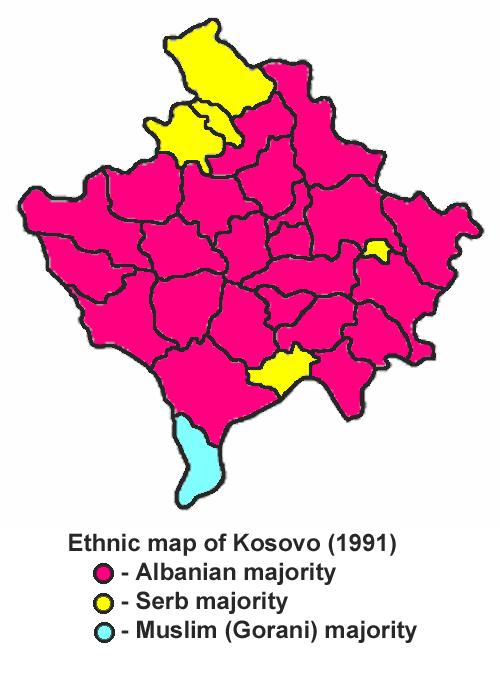

The estimation of the representation of ethnic groups in Kosovo in 1991 is as follows:

- more than 80% of Albanians (mainly Muslims)

- around 10% of Serbs

- more than 3% of other Muslims including Bosniaks

- around 7% of other ethnic groups

Since his election as President of Serbia in May 1989 (reelection in 1992), Milošević tried to reduce Kosovo’s autonomy within Serbia. In fact, Kosovo, along with Voljvodina, were autonomous Serbian provinces that enjoyed a high degree of independence since the 1974 Constitution. However, this Constitution was heavily amended when Milošević rose to power. Besides, the Albanian population suffered from discrimination: their media and news outlets were restricted and many Albanians lost their job in favour of Serbian workers.

In 1996, the Kosovo Liberation Army was founded in order to give Kosovo its independence from the Yugoslav Federation and more specifically from Milošević’s Serbia. By the way, Milošević became the President of Yugoslavia in 1997.

The Kosovo Liberation Army enjoyed the support of Albanians in Albania who smuggled weapons to them. These weapons mainly stemmed from stolen police and military stocks.

B. The Conflict

An open war broke out in February 1998 between the Kosovo Liberation Army and Serbian forces including the Yugoslav Army. Kosovan Albanians resorted to a guerrilla mode of operation targeting Serbian military and police forces.

Milošević’s troops massacred several families of alleged insurgents at the beginning of the conflict which sparked a massive uprising in Kosovo. Serbian forces then used this insurrection as a justification for their “counter-terrorism” actions including chasing out Albanian populations from Kosovo.

The War in Kosovo is no exception to the pattern of Yugoslav wars. Serbian forces massacred 45 Kosovan Albanians in January 1999 in the small town of Račak, as an act of vengeance against violence committed by separatists in the region.

In March 1999, NATO intervened in Kosovo, despite Yugoslavia’s refusal. As a matter of fact, NATO considered the situation in Kosovo as a “humanitarian war”. The Organisation then performed air strikes on Serbian positions. However, the way bombings were carried out was not approved by the UN, their usefulness was sometimes questioned and they also killed hundreds of civilians.

C. The End of the war and the current situation in Kosovo

Eventually, the Kumanovo Treaty put an end to the war in June 1999. The UN Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) took charge of the country along with NATO, under a UN mandate, to ensure peace there.

The UNMIK still operates in Kosovo today though its presence seems to be incidental given that Kosovo declared its independence in February 2008. Nevertheless, neither Serbia nor the UN and the EU recognize Kosovo as an independent and sovereign state. Nowadays, 116 countries in the world recognise Kosovo’s independence.

The Kosovan government wields a de facto power over its territory even though its Northern regions, mainly inhabited by Kosovan Serbs, seek to maintain the country within Serbia.

VI. The International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia (ICTY)

In May 1993, the United Nations established the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in the Hague, Netherlands, in order to prosecute the perpetrators of crimes committed during the 1990s Yugoslav Wars.

The ICTY was eventually dissolved in 2017 and replaced by the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT). The role of the latter was to supervise convicted’s conditions of detention and handle potential appeal proceedings.

The ICTY indicted a total of 161 people: 94 Serbs, 29 Croats, 9 Bosniaks, 9 Albanians, 2 Macedonians and 2 Montenegrins. Out of them, 89 were convicted: 62 Serbs, 18 Croats, 5 Bosniaks, 1 Albanian, 1 Macedonian, 2 Montenegrins. Here are some of them:

Slobodan Milošević

He was the Serbian President between 1989 and 1997, he then became the Yugoslav President until 2000.

He died in 2006 before a verdict could be reached. However, he was indicted on 66 counts of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo.

General Ratko Mladić (2021)

He led Serbian forces in Bosnia. He currently serves a life sentence in prison for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

Radovan Karadžić (2019)

He was the leader of the Republika Srpska in Bosnia. Like Mladić, he serves a life sentence in prison for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

General Radislav Krstić (2004)

He was a Serbian General who was recognised responsible for the massacre of Srebrenica in Bosnia in July 1995. During this event, that was qualified as a genocide by the ICTY, Bosnian Serbs killed more than 7,000 Bosnian men and boys.

Jadranko Prlić (2017)

He was the Prime Minister of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia, the unrecognized and self-proclaimed Croatian proto-state within Bosnia. The ICTY sentenced him to 25 years in prison for crimes against humanity, war crimes and violation of the Geneva Conventions.

The Geneva Conventions are actually 4 treaties and 3 protocols that constitute the basis for the protection of wartime prisoners, wounded and sick people, and civilians in and around war-zones.

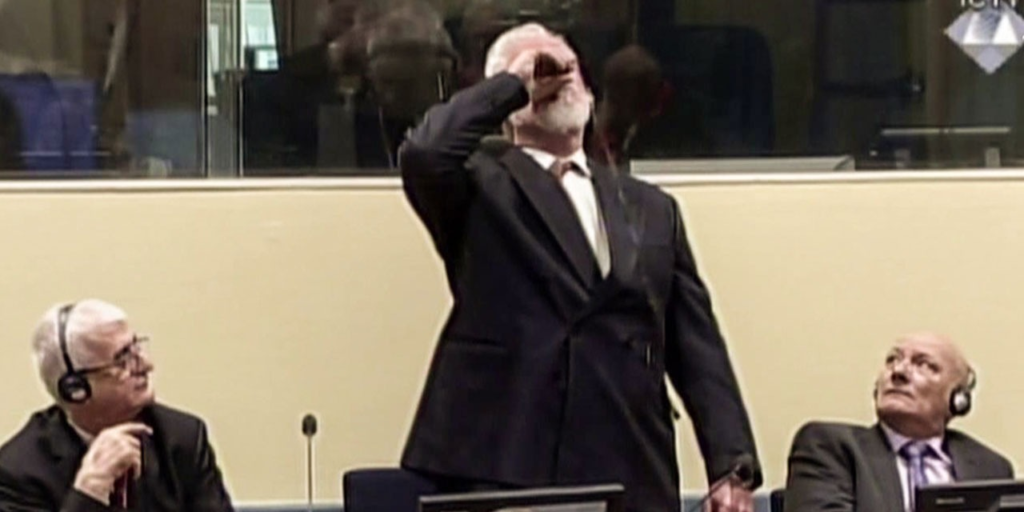

General Slobodan Praljak (2017)

He was a Bosnian Croat in the army of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia. He committed crimes against humanity, war crimes and violations of the Geneva Conventions. That’s why he had to serve 20 years in prison.

BUT during the pronouncement of his judgement, he addressed the judges and told them that he was not a war criminal and that he rejected their verdict. He then proceeded to drink poison and later died in a hospital.

Haradin Bala (2007)

He was a commander of the Kosovo Liberation Army. Because he committed war crimes in the Lapušnik prisoner camp, he was sentenced to 13 years of prison. However, he enjoyed an early release in 2013.

4 Comments

The Colour revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan – geopol-trotters · 31 December 2023 at 10:09 pm

[…] Following the 2000 general elections (presidential and parliamentary), Slobodan Milošević and his socialist party were declared victorious. Milošević was leading Serbia and Yugoslavia since the 1980s. If you want more information on him, read this article on the 1990s wars in Yugoslavia! […]

From Clinton to Biden: a look back on 30 years of US leadership – geopol-trotters · 25 September 2023 at 6:31 am

[…] why Bill Clinton didn’t send troops in Rwanda in 1994 and was reluctant to intervene in the various Balkan wars in the 1990s. Besides, Bill Clinton’s foreign policy focused primarily on spreading democracy and the […]

Humiliation in International Relations – geopol-trotters · 17 August 2023 at 2:26 pm

[…] US for decision-making and it remained quite dependent on the US for foreign interventions like in Kosovo in 1999 and in Libya in […]

The European Union: how does it work ? - geopol-trotters · 18 November 2022 at 6:17 am

[…] has been given regarding a potential integration into the EU. The EU also engaged discussions with Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, 2 Balkan countries wishing to join […]