Naval Power’s Role in a National Defence Strategy

What you want to understand… 🤔

- What are the advantages of naval power compared to land and air forces?

- What is the concept of Freedom of the Seas?

- What is the concept of naval suasion developed by Edward Luttwak?

- What are the different courses of action that navies can undertake?

- Why is a navy vital economically and logistically?

Since 71% of the Earth surface is covered by water, seas constitute a strategic theatre for military operations. Countries with proper means can evolve and intervene far from their shores, wherever their interests are at stake on seas or on foreign shores. Indeed, the international law principle of Freedom of the Seas grants freedom of navigation outside territorial waters both in peace and war time. We will see how countries utilize naval power to guarantee their territorial integrity, protect their citizens and secure their interests off-shore.

When we speak of naval power we refer to “navy, coast guard, naval infantry and their shore establishment” 1. Naval operations are carried out by surface ships, submarines, naval infantry and/or seaborne aviation. They fight both naval and land threats within the framework of a country’s defence policy. The latter should enable to repel potential attacks (or limit their damages) and dissuade enemies by presenting an unvanquishable military force2].

I. Naval Power overcoming limits faced by land and air powers

A. The prominence of the material factor over the human one

The absence of human habitations at sea reduces the probability of having collateral civilian damages since threats can be relatively more easily identified. However, it is less true in territorial waters where friendly, enemy and neutral entities can coexist thus creating a “bystander problem” 3.

Besides, naval power is less manpower-intensive than land forces because its strength relies primarily on the quality of its vessels, weapons and sensors. Fewer soldiers are required and those aboard are technicians and officers. As a result, naval warfare is waged primarily against enemy materiel4.

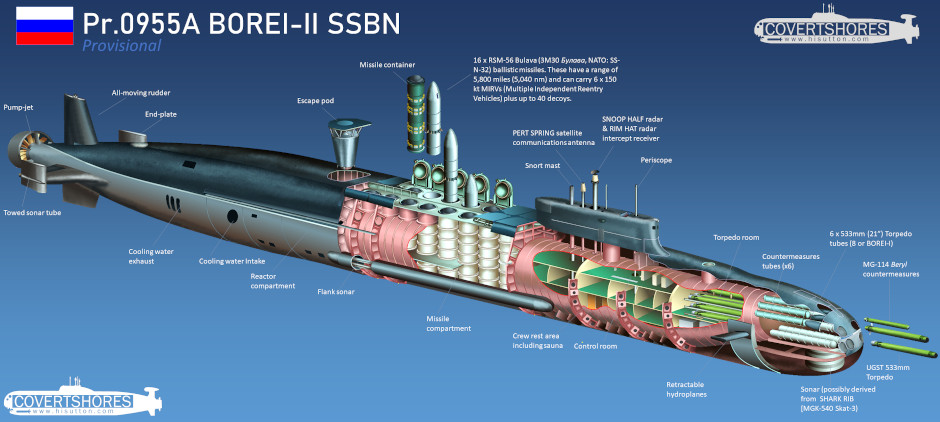

The number of casualties being inferior to land warfare, naval power is privileged when possible in order to limit human life loses. Furthermore, as naval power is more sensitive to technological innovations, countries with sufficient technical and financial means can rapidly take an edge over their opponents. For instance, 13 countries in the world have aircraft carriers and only 6 of them possess nuclear submarines. Those countries have a considerable advantage since they can project air forces worldwide without relying on land bases and their submarines stay submerged longer and are faster than other submarines. Gaining the edge in naval welfare rests mainly upon quality than quantity5. For instance, unlike the number of troops, human capital (i.e. crews’ technical and tactical skills) is paramount in the good undertaking of naval missions.

Furthermore, the importance of having a strong naval force is obvious in fleet-versus-fleet battles that are short, rare but also decisive for the rest of the war, more than major land battles6. Since the victor has to destroy its enemy’s fleet, the latter cannot bounce back quickly. Indeed, it takes too much time to rebuild large naval combat units and properly train crews. Julian Corbett adds that wars cannot be won solely on maritime victories but few of them are sufficient to remove from the “war equation” an enemy’s naval power7.

B. A permanent readiness to act and occupy strategic points of the globe

Naval forces are really valuable because they can remain on station at sea for long periods of time due to their self-sustaining ability, unlike air forces with land support. In parallel, they are flexible and can rapidly shift from one mission to another. Naval power is thus characterised by its permanent readiness to intervene whatever the mission and wherever it is needed. Indeed, a country’s navy is deployed before the outbreak of a conflict: the same equipment is used both in peacetime and in wartime. A navy can reach an enemy’s doorstep easily due to the principle of freedom of the seas: there is no legal constraint for a country to move its pieces freely on the world chessboard. Moreover, naval power is faster and more mobile than land power. In fact, it can move in any direction, at a high speed and stealthily when it comes to submarines and certain ships. For instance, large vessels like aircraft carriers or destroyers can change their locations “by up to 1,000 miles within 72 hours” 8.

Naval power’s two main roles are ensuring sea control or sea denial. According to Milan Vego, sea control means controlling a significant maritime area in which an actor is free to undertake a great variety of actions9. However, sea denial is more defence oriented and seeks to prevent a country from acquiring sea control. It can be achieved with submarines whose stealth hinders a country’s knowledge of whether it actually controls a given maritime area. Nowadays, sea control is difficult to ensure since there is a proliferation of submarines. In fact, in the 2000s the number of submarines in service rose by 50%, especially in Asia10. Sea mines are also an inexpensive and highly efficient weapon to prevent sea control.

II. Naval power’s ability to undertake a wide range of actions

A. Naval suasion

In 1974, Edward Luttwak developed the concept of naval suasion, a combination of persuasion and dissuasion that can be declined into several forms11.

Its latent dimension refers to routine deployments and the concept of “fleet-in-being”. It means that naval forces can indirectly prevent conflicts just by presenting a latent threat. It can be used to either deter enemy offences or support allies. However, its effects are only indirect and often not planned. With regard to deterrence, the only fact that a country owns SSBNs (ballistic missile submarines), which pose a threat of nuclear retaliation, indirectly deters potential enemies from planning attacks.

As J.J.Widen underlined it in 2011, active naval suasion seeks primarily to “bring about specific reactions by the target in question” 12. The intent can be of a coercive or supportive nature. For instance, after World War I, the British navy patrolled in the Baltic Sea both to deter hostile undertakings by the new Soviet government and to back the White army as well as the newly independent Baltic states. Naval power is also a means to alter the status quo by compelling an opponent to change its behaviour. It was the case in 2013, in the East China Sea, where a Chinese frigate radar targeted a Japanese destroyer around of the Senkaku and Diaoy islands. Radar targeting constitutes the last phase before actually launching a strike. China, Japan and Taiwan claim the ownership of these islets even though Japan seems to control them since it has built facilities on them13. However, the Chinese move on the Japanese vessel was a way to make Japan acknowledge the existence of a territorial dispute. Tensions between France and Turkey in the Mediterranean Sea in summer 2020 are a similar example. In fact, Turkey radar targeted a French ship that was under NATO command to uphold the arm embargo on Libya14. Turkey tried to compel this ship to leave the area and not to meddle in Turkish activities in the region.

B. Representative of a country’s national power

Freedom of the seas, a noticeable presence and a multi-task ability make naval power, more than land and air ones, a privileged representative of a country’s national sovereignty and power 15. And here lies what Luttwak calls the “visibility/viability dilemma” 16. According to him, naval power should focus on being more visible than viable for fighting. Indeed, naval power’s usefulness is underlined mainly in peacetime during naval suasion missions such as “show-of-force” and “flag-showing”. For instance, in January 2021, the Iranian navy conducted large-scale military drills in the Persian Gulf17, 18.

The goal was to signal to regional rivals and the US that Iran was ready to wage a war. Even though overall the Iranian navy is no match for the US one, this provocative move was a way for Iran to gain leverage. In fact, Iran threatens the US with the possibility of triggering a war that the US couldn’t avoid and that would be detrimental for them. As a matter of fact, more than a disruption of the world supply of oil, there would be risks of spill-overs and of a stronger polarization along religious and ethnic lines in the region. Besides, without Iran there would be no reason for other Middle East countries to seek US protection. Here the visibility of the Iranian power is more important than its actual viability.

III. Naval Power as a defender of vital economic activities

A. The importance of defending merchant shipping

In our globalized world, countries are interdependent and rely heavily on merchant shipping. The security of maritime routes is crucial for most countries since 90% of the world trade of goods is done via these routes. Therefore, most nations’ chance of winning a war rests upon their ability to “maintain control of the oceans” 19. A country’s ability to sustain its activities during a war depends on the protection of the sea lines of communication (SLOCs). When the latter are closed, a country’s logistical chain, which relies greatly on material supplies travelling by seas, is deeply damaged. As a result, the support of its war effort is hampered20. The role of one’s naval forces is thus to protect its civil merchant fleet from commerce raiding by enemies seeking to disrupt its logistical chain. It also has to protect the sources of shipping, often its allies, and the EEZ where it possesses natural resources.

B. The importance of defending littorals

Naval power is essential for defending littorals that are areas of great economic significance and major population centres. Indeed, commercial ships travel from ports to ports that are the main connections between overseas territories and hinterlands. Besides, in 2035 more than 75% of the world population is expected to live within 100km from shores21. Thus, a country’s population’s security hinges considerably on its naval power’s ability to prevent enemy bombings and landings.

C. Naval power assuming constabulary missions

A country’s defence policy also includes naval constabulary missions in order to create safe and reassuring conditions for one’s trade partners. A strong naval power is important for facing maritime threats and in particular piracy. For instance, in 2008 the EU launched Operation Atalanta that aimed to fight piracy off Somalian shores. The same year 20,000 ships were passing through the Gulf of Aden, making it a major crossing point for world trade. Corvettes and small vessels are best suited for the defence of EEZs and more broadly for counter-piracy and counter-terrorism missions. They represented the large majority of ships built at the end of the 2000s22.

Conclusion

We have now come to the conclusion that a country’s defence policy would be incomplete and inefficient without naval power. The prominence of the technical and material factors limits the number of human casualties and gives naval warfare a decisive character which entices countries to build a strong naval power. Besides, naval power is essential for a country’s defence policy since it constitutes highly flexible, mobile and self-sustaining forces that can also be stealth. Moreover, “weak” countries can get an important pouvoir de nuisance and focus on sea denial. Naval power’s value lies also in its multi-task capacity and in the variety of leverage means it offers. In fact, it is a representative of a country’s national power due to its ability to be as supportive towards allies as deterrent and coercive towards enemies. We also showed in this essay that naval power is an important component of a country’s defence policy because it can ensure the protection of its vital economic and logistical assets such as littorals and maritime routes.

Sources

- Vego, Milan. On Naval Power. Strategos, vol 1, no 1, 2017, p. 43-67.

- rt, Robert J. To What Ends Military Power? International Security, vol. 4, no 4, 1980, p. 3. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.2307/2626666.

- Lombardi, Ben. The Future Maritime Operating Environment and the Role of Naval Power. Centre for Operational Research and Analysis, 2016.

- Vego, Milan. On Naval Warfare. Tidskrift i Sjöväsendet, no 1, 2010, p. 73‑92.

- Vego (2010)

- Vego (2010)

- Corbett, Julian. Some Principles of Maritime Strategy, Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, Maryland, 2011.

- Vego (2010)

- Vego, Milan. Operational warfare at sea: theory and practice. Routledge, London, 2009.

- Bateman, Sam. Perils of the Deep: The Danger of Submarine Proliferation in the Seas of East Asia, Asian Security, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2011

- Luttwak, Edward. The political uses of sea power. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974.

- Widen, J. J. Naval Diplomacy – A Theoretical Approach, Diplomacy & Statecraft, vol. 22, n°4, December 2011, p. 715‑33. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1080/09592296.2011.625830.

- Kyodo. Taiwan Activists Threaten to Land on Senkakus If Japan Doesn’t Remove Facilities. The Japan Times, March 2, 2015. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/03/02/national/politics-diplomacy/taiwan-activists-threaten-to-land-on-senkakus-if-japan-doesnt-remove-facilities/.

- France Blasts ‘Extremely Aggressive’ Turkish Intervention against NATO Mission Targeting Libyan Arms. France 24, June 17, 2020. https://www.france24.com/en/20200617-france-blasts-extremely-aggressive-turkish-intervention-against-nato-mission-targeting-libyan-arms.

- Widen (2011)

- Luttwak (1974)

- Motamedi, Maziar. Iran Unveils Its Largest Military Vessel during Missile Drill. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/1/13/iran-unveils-its-largest-military-vessel-in-navy-drill.

- Iran Showcases Its Naval Might in Front of US Forces in the Persian Gulf: Video. AMN – Al-Masdar News, January 7, 2021. https://www.almasdarnews.com/article/iran-showcases-its-naval-might-in-front-of-us-forces-in-the-persian-gulf-video/.

- Dunnigan, James F. “The Navy: On the Surface”. How to make war: a comprehensive guide to modern warfare in the twenty-first century, 4th ed, Quill, 2003, p. 221.

- Brooks, Linton F. Naval Power and National Security: The Case for the Maritime Strategy. International Security, vol. 11, no 2, 1986. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.2307/2538958.

- Haslett, Simon K. Coastal Systems, Routledge, 2009. ISBN 9780415440608.

- Kraska, James. Maritime Power and the Law of the Sea: Expeditionary Operations in World Politics, Oxford University Press, 2011.

2 Comments

Twicsy · 24 June 2022 at 12:47 pm

Wow, this article is nice, my younger sister is analyzing such things, so I

am going to convey her.

SOMALIA: al-Qaeda’s base in Eastern Africa - geopol-trotters · 26 December 2022 at 8:20 pm

[…] EU (Operation Atalante since 2009), the US, China and Russia regularly conduct naval patrols to secure the area. Consequently, piracy was considered gone by 2012. Nonetheless, we should not […]