TURKEY and RUSSIA : a strategic alliance ?

What you want to understand… 🤔

- Do past rivalries impact current Russian-Turkish relations?

- What was Turkey’s strategy in joining NATO in 1952? How does its current relationship with Russia align with this strategy?

- To what extent are Russian and Turkish economies complementary?

- How are economic interests and geopolitical oppositions compartmentalised?

I. History

A. Imperial rivalries (16th to early 20th century)

From the 16th to the 20th century, the relation between Turkey and Russia boiled down to the Russo-Turkish wars. During the 16th and the 17th centuries, the Ottoman Empire laid its hands on the shores of the Black sea as the Russian empire was focusing on eastern territories in Asia.

However, under the rule of Peter the Great (1682-1725) and then Catherine II the Great (1762-1793), the Russian Empire endeavoured to expand southwards to the Black sea and later to the Caucasus and the Balkans in order to secure an access to international commercial routes, especially those of the Mediterranean sea.

Russia managed to gain some territories on the Northern shores of the Black sea at the expense of the Ottoman Empire whose weight on the international stage was declining. It resulted in the emergence of the Eastern question i.e. France and Great Britain worried about Russia’s growing influence and Turkey’s inability to contain it.

That’s why France and Great Britain supported the Ottoman Empire during the Crimean War (1853-1856) against Russia. Eventually, they came out victorious and significantly weakened Russia’s regional influence, but the question of the decline of the Ottoman Empire remained unresolved. Besides, the outcome of the war deeply destabilised the Russian Empire that then undertook modernising structural reforms.

During the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, conflicts kept occurring between the two rivals through alliances and proxy wars.

The two empires fought each other during World War I. However, they both eventually got overthrown : in 1917 for Russia and in 1923 for Turkey.

B. The “sincere friendship” (1920s)

In the early 1920s, the relationship warmed up as Lenin and Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) got on well. Their relation was characterised as the “sincere friendship”.

Moreover, the Soviet government provided gold reserves and ammunitions to Turkish revolutionaries during the Turkish war of Independence (1919-1923). Then, they signed the Treaty of Brotherhood in 1921 stating that they stood together in the struggle against imperialism. In the 1920s and 1930s, the USSR participated in Turkey’s industrialisation by building textile factories and negotiating export deals.

C. On two opposite sides during the Cold War (1947-1991)

Even if Turkey entered World War II on the Allies’ side, it quickly adopted a neutral stance until the end of the conflict. Relations with the USSR then deteriorated as Russian leaders laid territorial claims and demanded to renegotiate some treaties. For instance, they sought to modify the Montreux Convention (1936) that gave Turkey control over both the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus Strait.

Turkish accession to NATO (1952)

As Turkish-Russian relations were at their lowest, Turkey took part in the Korean War (1950-1953) on the US side and joined NATO in 1952.

However, we should bear in mind that it was a transactional rather than an ideological rapprochement. As a matter of fact, Turkey didn’t share a common vision of values with the West. Turkey’s strategic geographical location for NATO and their common interest to contain the USSR’s regional influence were enough to motivate the Turkish accession to the trans-Atlantic alliance.

Besides, as Turkey was not fully aligned ideologically with the West, it could have been considered as a potential enemy by the latter. By entering the Alliance, Turkey ensured that no harm would come from the West. In parallel, it managed to maintain its sovereignty and ideological independence. As the saying goes: “Keep your friends close, and your enemies closer“.

D. A renewed friendship (1991-2000s)

Following the collapse of the USSR in 1989-1991, Turkey feared that it had lost its defining role in the Alliance. Therefore, it sought to diversify its international relations and turned towards its Middle-Eastern neighbours, the Balkans and newly independent Soviet Republics in the Caucasus and Central Asia. As a consequence, old geopolitical rivalries with Russia resurfaced. These tensions rapidly faded out as they rapidly increased their trade volume and economic cooperation. Indeed, Russia became Turkey’s first energy provider, Turkey became the first destination for Russian tourists and many Turkish companies set up their business in Russia. That’s why the 2000s is qualified as the “golden decade of friendship” between the two countries.

II. Economic complementarity

A. Russia’s dependence for access to the Mediterranean

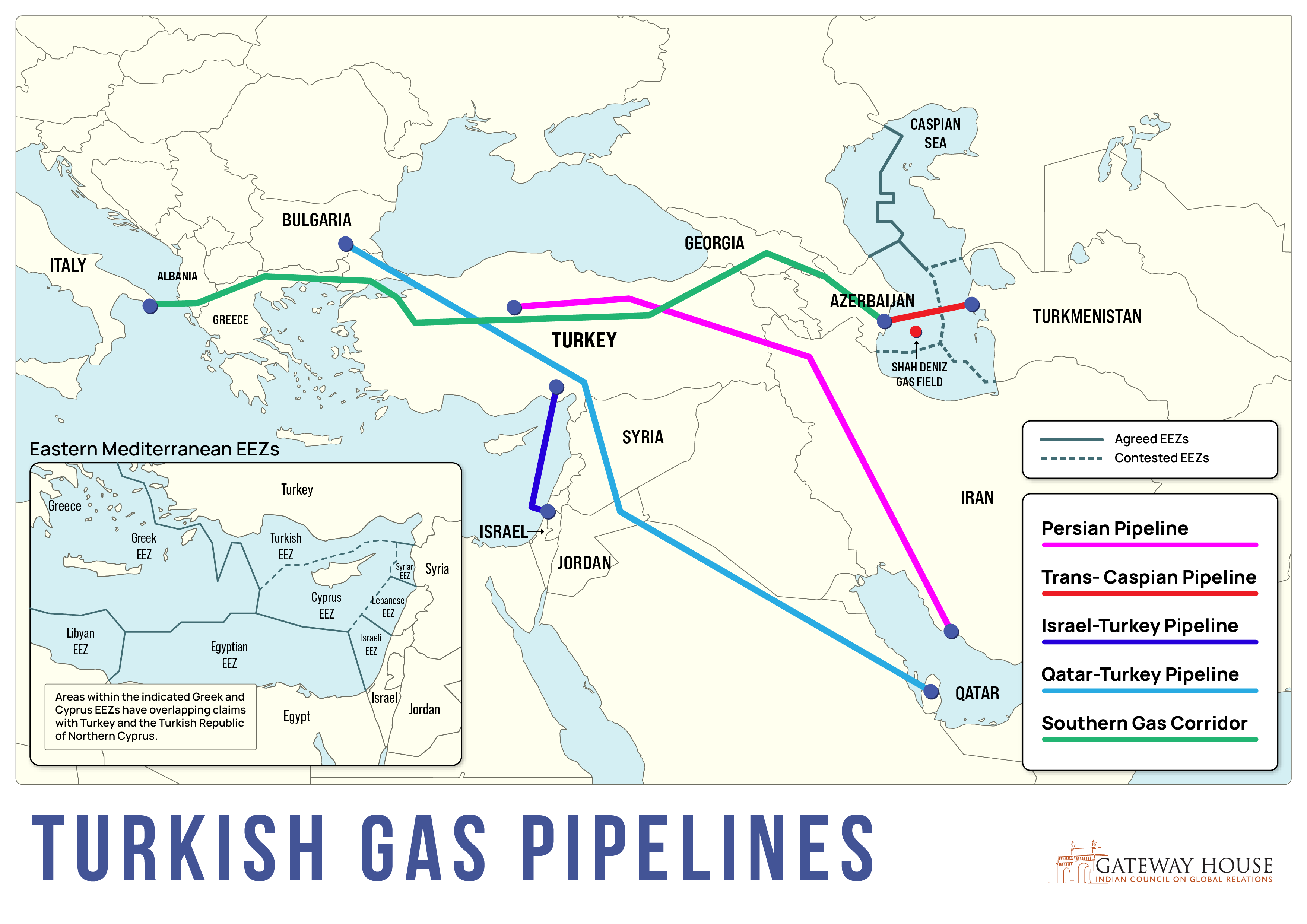

Since Russia doesn’t have a direct access to warm waters, it needs to go through the Bosphorus Strait and the Dardanelles to get out of the Black sea. It is vital for Russian exports and geopolitical connections with Mediterranean countries like Syria and Libya. As a matter of fact, Turkey controls both the Bosporus Strait and the Dardanelles since the 1936 Montreux Conference. Therefore, Russia has no choice but to get along with Turkey so as to facilitate the passage of its ships.

B. Each has what the other needs

On one hand, Russia has energetic resources that it seeks to export in order to maintain its revenues as it is progressively isolating itself on the international stage. On the other hand, Russia needs to import consumption goods and industrial products.

As for Turkey, its economy is based on manufacturing and is export-oriented. It lacks energetic resources to support it, that’s why it needs to import them. Moreover, so as to avoid over-production and the depletion of its stocks of foreign currencies, it needs a reliable long-term partner.

Therefore, since Russia has energetic resources that Turkey lacks and since Turkey has a strong manufacturing industry unlike Russia, we can easily understand why these two countries have become economic partners.

For instance, since 2003, Russian gas is exported to Turkey through the Blue Stream pipeline that discharges 16 billion cubic metres of gas per year. The TurkStream gas pipeline, with the approximate same capacity as the Blue Stream, also contributes to the Russia-Turkey economic partnership since 2020. In 2021, Russia provided 45% of Turkish natural gas and 25% of Turkish oil.

In the energy sector, we can also mention that, in 2018, Turkey gave a Russian conglomerate the responsibility to build its first nuclear central in Akkuyu. This central should eventually provide 10% of Turkey’s electricity.

It is also worth noting that both countries’ economies are weak.

- Russia suffers from international economic sanctions, an undiversified production, a poor investment climate and a lack of investment in its infrastructures.

- Turkey experiences a high inflation since the 2000s because the government has sought to boost the economy at all costs at the expense of its stability. Besides, Turkey’s trade war with the US in 2018 dealt a blow to its economy as its currency depreciated and inflation surged.

C. Impact of the war in Ukraine

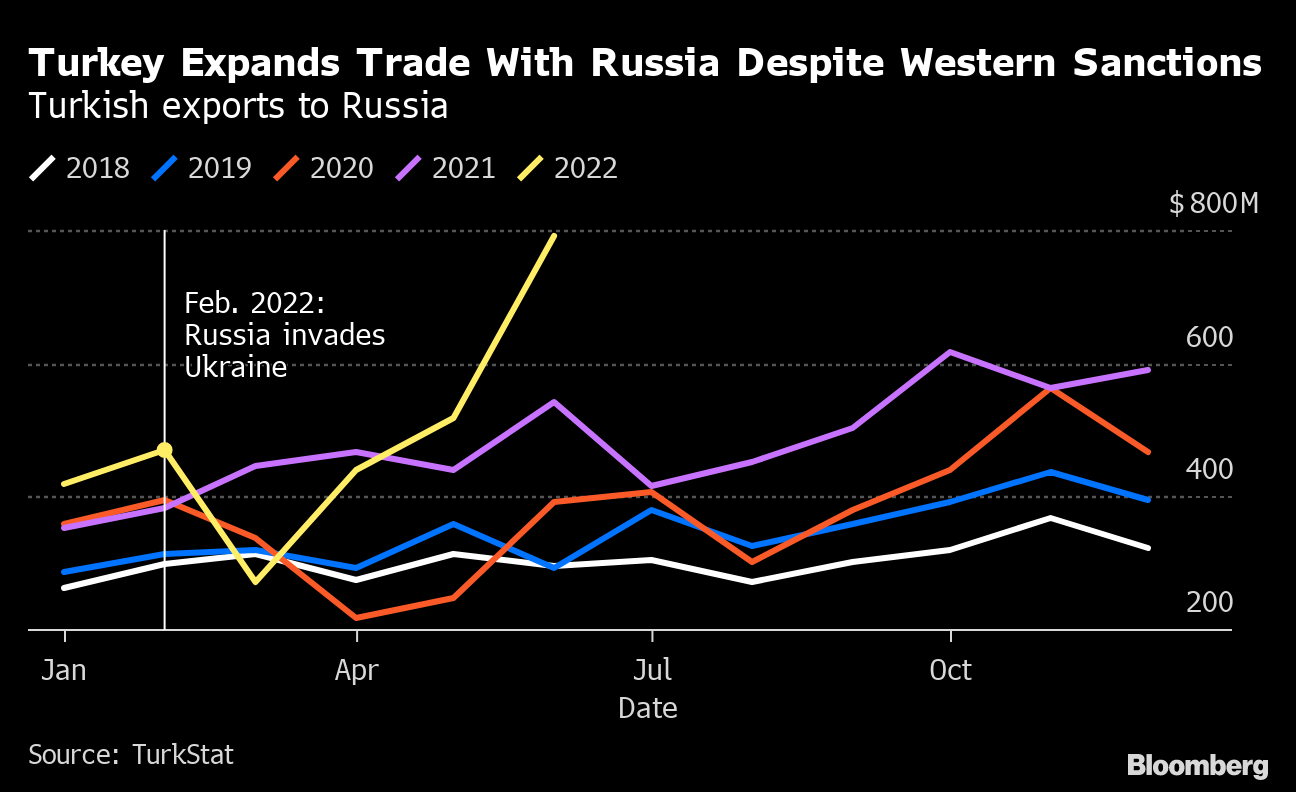

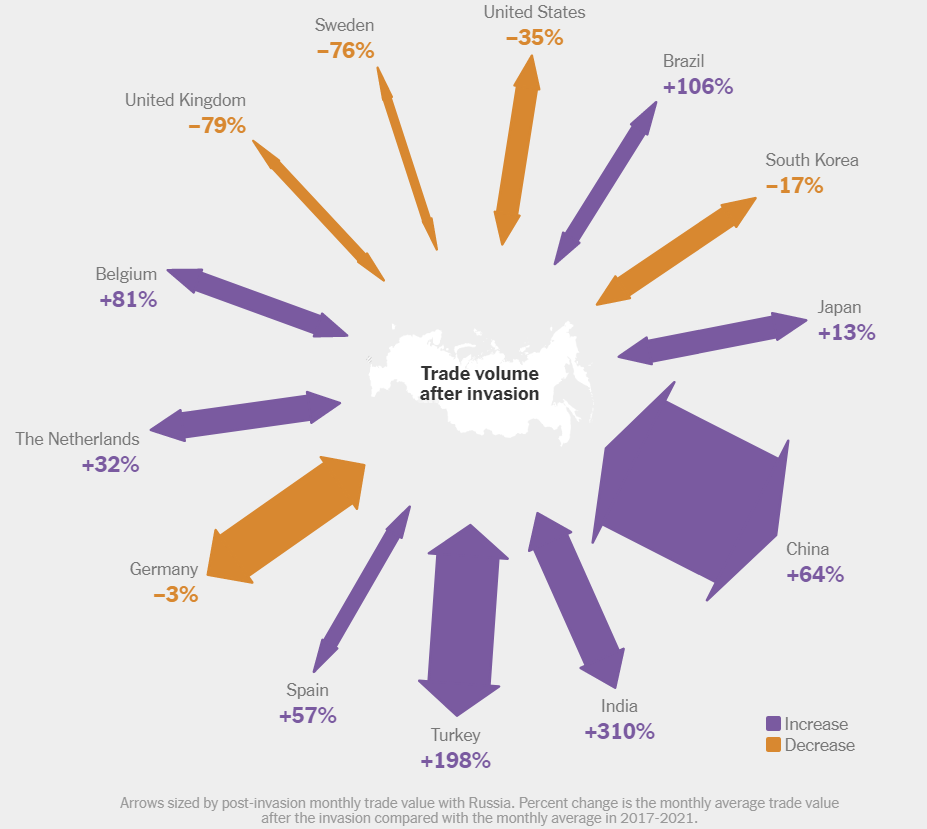

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, economic exchanges have significantly increased between Russia and Turkey. These exchanges notably include energy, electronics, engineering products and food products

In August 2022, they signed a deal for economic cooperation with the objective of reaching $100 billion/year-worth of trade exchanges.

Moreover, rouble is still accepted in Turkey. Thus, the latter represents an alternative destination for Russian investments that are not welcomed anymore in Europe.

With the war, Turkey has become a trade platform for many exports destined to Russia as many countries want to circumvent international sanctions to keep on dealing with Russia. Furthermore, Turkey is progressively turning into a major gas hub as it receives gas not only from Russia but also from the Middle East. It then supplies it to Europe which allows Russia to circumvent the Nord Stream pipeline that connects it to Germany through the Baltic sea.

III. Geopolitical tensions

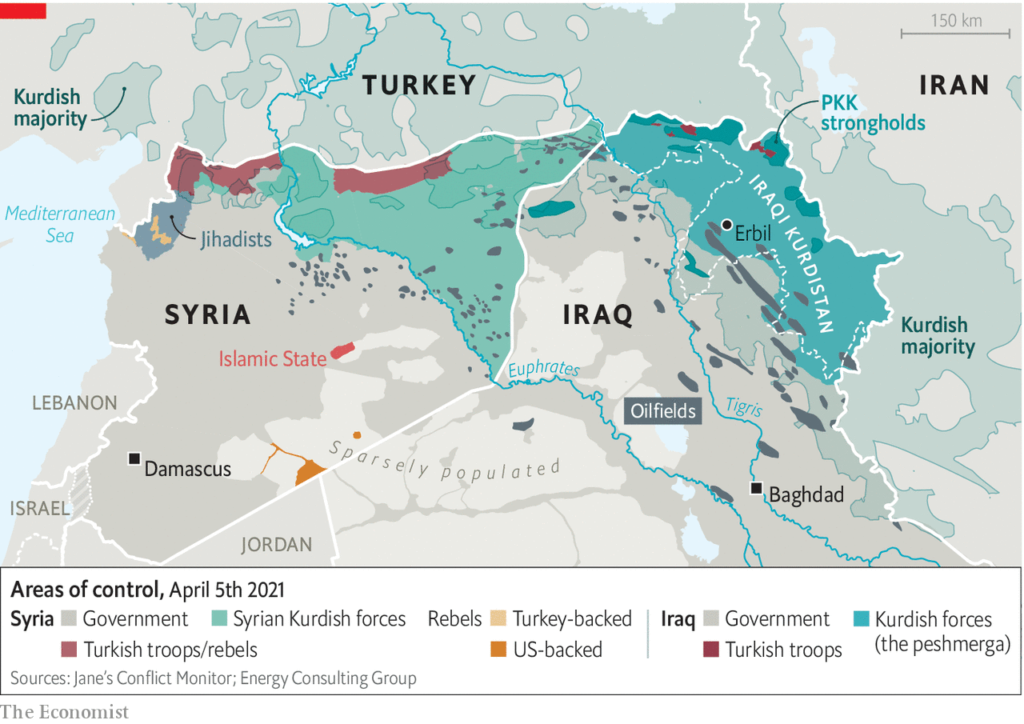

In Syria, Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh and Ukraine, Turkey and Russia stand on opposite sides and even fight each other, through indirect means though.

A. Syria

In Syria, Putin supports Bashar al Assad’s regime in the fight against jihadist terrorist groups. Russia has thus received the control of the Syrian port of Tartus.

In Syria, Turkey is more concerned about the Kurdish influence along its Southern border.

Even if Kurdish fighters (Peshmerga) fight Daesh and al Qaeda, Russia has refused to arm them in part because they oppose the Syrian government. Therefore, it makes it easier for Turkey to deal with Putin with regards to the Kurdish question in Syria. However, we should also mention that Ankara has already called for the removal of the Assad regime by the past.

B. Libya

In Libya, Turkey supports the official government of President Faïez Sarraj that is recognised by the UN. In fact, Sarraj has political views close to those of Erdogan since he promotes an Islamic mode of governance.

On the contrary, Russia and its Wagner Group back the opposition led by General Haftar from Eastern Libya. Since he embodies the resistance to the spread of Islamism in the Maghreb, Haftar is also supported, though unofficially, by a variety of state actors including France, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates.

The reasons are manifold why Turkey and Russia supports opposite camps. Nevertheless, I will later dedicate a whole article to the war in Libya following the Arab Spring of 2011 and the fall of Muhammad Kaddafi

C. Nagorno-Karabakh

In the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, again Russia and Turkey end up facing each other. Turkey has Azerbaijan’s back while Russia is more or less on the Armenian side. For more info about the Nargorno-Karabakh conflict, read the dedicated article: ARMENIA and AZERBAIJAN: the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

D. Ukraine

As early as 2014, Turkey was concerned about Russian territorial claims on Ukrainian lands. As a matter of fact, Erdogan holds pan-Turkish ambitions and therefore wanted to make sure that no harm was caused to Crimean Tartars, an indigenous Turkish ethnic group of Crimea.

Besides, Turkey currently sides with Western powers to provide weapons such as drones and armoured vehicles to Ukraine. Nevertheless, it has declined to impose sanctions on Russia as it has sought to play a mediating role between belligerents.

E. Conflicting zones of influence in Central Asia and in the Black Sea

Erdogan’s pan-Turkic Eurasian strategy may threaten Russia’s influence in its Near Abroad. Indeed, Turkey is trying to establish special economic, political, military and cultural ties with Central Asian countries like Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Russia’s recent takeovers of Abkhazia (Western Georgian Republic), Crimea and Southern Ukraine have reinforced its influence in the Black Sea, a strategic region where Turkey has long been a game-maker.

IV. Compartmentalisation: combining similar economic interests with conflicting geopolitical interests

Compartmentalisation refers to the separation between booming economic relations and geopolitical tensions. As a matter of fact, Turkey and Russia have decided to ignore their disagreements and work around each other when their interests are not aligned, while fostering economic cooperation.

Erdogan and Putin are pragmatic leaders. They focus on current issues rather than past rivalries. They try to meet their respective economic needs rather than to block any kind of cooperation because of unrelated disagreements in other areas.

V. How both benefit from annoying NATO

Building stronger connections with Turkey is a way for Russia to sow dissent among NATO ranks. Indeed, it seeks to weaken NATO’s unity by encouraging Turkey to express its autonomy, thus making it increase its unpredictability on the international stage.

Turkey is satisfied with being portrayed as a sort of swing state between the West and a block of countries made up of Russia, China and Iran. In fact, Turkey sees its relation with Russia as a means to show its strategic independence to the Western powers and tell them that they shouldn’t take its cooperation for granted just because it belongs to NATO. As a result, Turkey gets a sort of special status with a lot of leverage within the Western block.

Despite Erdogan’s aggressive rhetoric, Islamist views and sectarian policies, that set a substantial distance with other NATO members, Turkey is not ready to give up on its NATO membership. As a matter of fact, NATO gives Turkey more weight on the international stage. For example, in Syria and in the Black Sea, Ankara is calling on NATO to prevent Russia from extending its influence in the Middle East.

Besides, Turkey wouldn’t give up on the guarantee of security that Article 5 of NATO’s Treaty provides. It is especially true if we imagine a potential security partnership with Russia whose military capacities have shown their limits during the war in Ukraine. Turkey’s NATO membership is its most important institutionalised connection in the field of security, which makes it difficult to believe that Erdogan would foregone it at the drop of a hat.

VI. Is this a strategic alliance?

The relationship between Turkey and Russia is not institutionalised i.e. there isn’t any bind between them that cannot be easily unbound. Moreover, they don’t have a shared and stable perspective on regional and global affairs. Besides, as we’ve seen, Turkey’s best interest is to maintain, at least officially, its strategic alliance with NATO as Russia doesn’t represent a credible alternative.

Therefore, it is wrong to talk about a strategic alliance between Russia and Turkey.

What we should bear in mind is that their relationship depends on short-term definitions of national interests and sudden domestic and geopolitical shifts.

Mistakes made by most commentators:

- Phases of rapprochement between the two powers are mistaken for evidence of the development of a strategic alliance.

- Too much importance is given to the trust factor and the personal relationship between Erdogan and Putin. This is so because both leaders have an autocratic style and thus belong to the “same side of History” according to President Biden’s portrayal of the world as an opposition between democracies and autocracies. The Russian and Turkish leaders are rational and pragmatic: they seek to get the most out of their partnership while maintaining their ability to move away if needed.

2 Comments

Humiliation in International Relations – geopol-trotters · 21 August 2023 at 3:04 pm

[…] culturally, politically or economically. It is also quite paradoxical to qualify China, Russia and Turkey as “emerging power” given their history and their weight in international […]

RUSSIA, a predator in AFRICA – geopol-trotters · 14 May 2023 at 4:40 am

[…] The war in Ukraine has disrupted Russian trade patterns with international partners, especially due to EU embargoes. That’s why the country has to find new markets since its whole economy rests upon the export of energetic resources (we discussed this topic in our article TURKEY and RUSSIA : a strategic alliance?). […]