HUMILIATION in International Relations

This article’s cover picture represents the Indonesian President Suharto signing an agreement with the IMF for the implementation of 50 measures of budgetary discipline on January 15, 1998. The IMF Director, Michael Camdessus, is standing on the left-hand side.

This article gathers my takeaways from Bertrand Badie’s “Humiliation in International Relations: a Pathology of contemporary international systems” (2014), which I initially read in French. The information provided here only reflects B. Badie’s view.

When I write “the Other”, I refer to countries that tend to be marginalised by Western powers that dominate the current international order.

3 things to remember from this book🤔

- Humiliation, through stigmatisation and marginalisation of alterity as well as administration of morality, is used to perpetuate a certain international order in which States compete for status and consider the Other not as a subject but as an object of power;

- “Emerging powers” is a catch-all category for countries that, instead of sharing geographical, cultural, political and economic characteristics, gather against a common enemy that humiliates them;

- A failure to imitate and integrate (nationaly, politically or socially) the Western world and globalisation is a source of humiliation that often causes one to become a staunch defender of one’s traditions and identity in rejection of the international order and its modernity.

Introduction

Theory: in the diversity of its appearances, humiliation has become a standard parameter of international relations.

Humiliation could be characterised as “any authoritarian assignment of a status inferior to the desired one, in a manner that does not conform to defined norms”.

Norms (laws, treaties, rights…) organise and establish humiliation so as to maintain a certain international order. Humiliation is a matter of violence, whether it is physical or symbolic, and can become constitutive of national narratives that forge national identities.

Humiliation is different from shame (no real hierarchical relation) and from trauma (tragic violence much more powerful than humiliation e.g. genocide).

I. Pitfalls of the Ordinary Lives of People

International relations can be seen as a competition for status like a zero-sum game where one’s power and prestige depend on another’s downgrading. Moreover, it’s worth noting that one’s status on the international stage entirely relies on its recognition by others, hence the room for humiliation. Newly independent countries in Africa and Asia in the 1960s and around the USSR in the 1990s asked for recognition but many were inflicted humiliation.

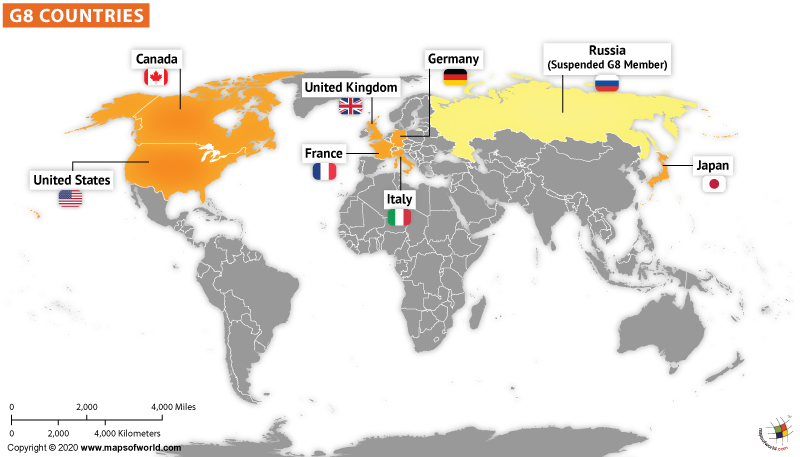

B. Badie analyses that, with the end of the Cold War in 1989, the logic of bipolarity has been replaced by a logic of co-optation and “minilateralism” (e.g. the G8) on which the recognition of one’s status now depends.

II. Humiliation, or Power without Rules

The author points out that conflicts no longer reflect power rivalries but rather power inequalities.

3 factors, linked to each other, induced the emergence of humiliation in the international system:

A. The concept of “just wars”

The concept of “just wars” formalised the end of equality and symmetry that existed between European monarchies during the Renaissance for example. With just wars, the enemy becomes hated and stigmatised such that waging war is no longer about maintaining one’s power but rather about restoring what is deemed good and right.

These wars create humiliation, which fuels revenge and further violence.

B. Interferences with social constructions

Waging war progressively adopted a social dimension in the international system because populations increasingly voiced their expectations and frustrations about it. Hence, wars lost their cold and mechanic aspect associated with the sole objective of conquering territories and power.

They took on a more emotional and social dimension as they became waged in the name of a people. Therefore, wars turned into a means to rank peoples and societies, which has paved the way for the stigmatisation of the Other and the development of xenophobia. For example, G.Clemenceau’s France did its best to humiliate Germany at the Paris Peace Conference (1919-1920).

C. Discovery of the Other

When Western powers encountered “inferior” powers, they put aside the common rules of respect that existed between powers of the same level and allowed themselves to objectify and humiliate the Other. It was the case with China, whose Summer Palace was sacked during the two Opium wars (1839-1842 and 1856-1860). The Other is not a subject but an object of power.

III. Types of Humiliation and their Diplomacies

Type 1: Humiliation by Lowering of Status

It consists in imposing onto the loser a dramatic degradation of its power status so as to marginalise him on the international stage. The emotional shock created for defeated populations leads to feelings of revenge.

Type 2: Humiliation through Denial of Equality

Westphalian States have tended to stigmatise alterity and consider the Other as inferior. However, humiliation is attenuated by Westphalian States’ seduction games to make the Other fall into their respective spheres of influence. Countries being humiliated in this way develop a high level of mistrust and a cautious approach to international cooperation.

Type 3: Humiliation by Relegation

Inequality of development leads to humiliation since one is immediately marginalised and considered not legitimate enough to participate in the international decision-making process, even when its own fate is at stake.

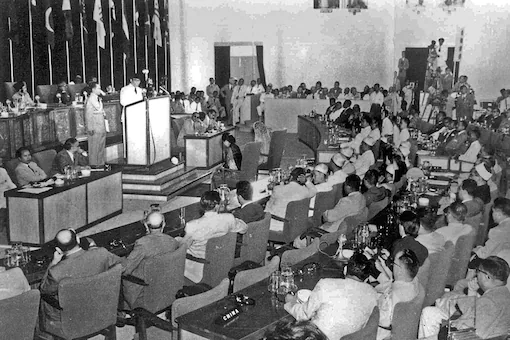

As a result, it creates resentment and a willingness to challenge the international order. For example, the Conference of the Non-Aligned in Bandung in 1955 aimed at contesting a bipolar world in which poor countries of Africa and Asia didn’t have their say.

Type 4: Humiliation through Stigmatisation

This kind of humiliation consists in marginalising another actor (e.g. a “Rogue State”) by condemning its political regime and its cultural values. The actor being marginalised then rejects the international order and all its symbols of domination.

IV. Constitutive Inequality: The Colonial Past

A. Exceptions and Outrages

Colonial domination banalised the denial of equality. In fact, rules that applied in the metropolis were no longer followed in colonies where stigmatisation became the local mode of governance. It resulted in excessive uses of violence to repress and punish any kind of dissent.

As a consequence, former colonised peoples developed a memory of inequality that has forged their national identities and influenced their international behaviour.

B. Pathways of Humiliation

Throughout the 20th century, many young African and Asian leaders were attracted by the Western world and its modernity. However, when they travelled and studied there, they faced its many contradictions.

They hoped for equality and integration but got humiliated as they were met with contempt and rejection.

C. New forms of Patronage

In order to guarantee stability and protect their interests after the independences, countries like France in Africa or the US in South-America, the Middle-East and Asia have sought to develop interpersonal connections with local leaders i.e. “clients” for whom they became sort of “patrons”. The former has a vital need of the latter . On the opposite, “patrons” only experience a marginal loss if they lose a “client”. Therefore, patrons can choose on a case-by-case basis when and where to intervene so as to maintain or topple a regime.

V. Structural Inequality: To be Outside the Elite

A. The Broken Dream of the ‘Middle Powers’

At the end of the Cold War, some “middle powers” were too small to impose themselves alone but too big to remain silent (Canada, France, Japan, Brazil…). That’s why multilateralism was needed.

However, it doesn’t mean that multipolarity developed out of bipolarity. According to B.Badie, after the the Cold War, an “apolar” (without pole) world emerged and here lies the issue of “middle powers”. They believe that we are in a multipolar world, which is still not the case, while at the same time keeping thought patterns that belong to a bipolar world, which doesn’t exist anymore.

In the wake of the Cold War, Europe, which comprised several “middle powers” like the UK, France and Germany, felt downgraded and thus humiliated because it no longer was the centre of attention of the global community, it got marginalised by the US for decision-making and it remained quite dependent on the US for foreign interventions like in Kosovo in 1999 and in Libya in 2011.

B. Emergent Powers and the Bonds of Past Humiliations

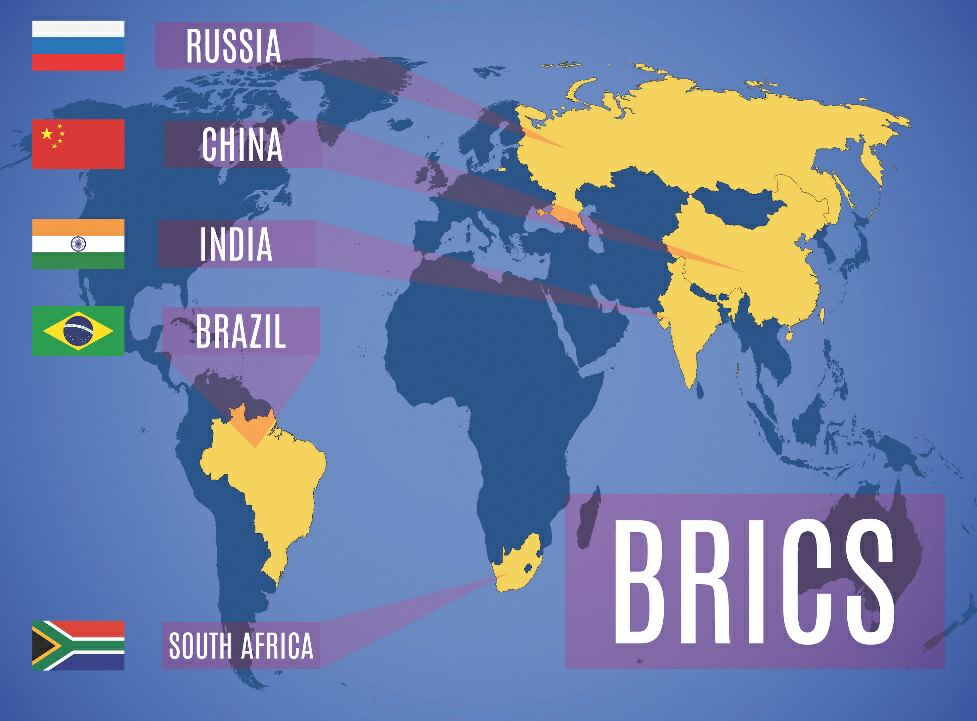

The category “emerging powers” fails to represent the diversity of identities and trajectories within it, whether it is geographically, culturally, politically or economically. It is also quite paradoxical to qualify China, Russia and Turkey as “emerging power” given their history and their weight in international relations.

Nonetheless, this label has become widely accepted and now structures how said-emerging powers identify themselves and how other actors perceive them.

As a matter of fact, these “emerging powers” don’t cooperate based on their similarities but rather based on a common enemy that at some point humiliated each of them. They even tend to over-emphasis this humiliation in the face of a system that marginalises them as it is their only way of making their voice heard.

C. Small Countries’ Narrow Range of Action

Their sovereignty doesn’t protect them from humiliation because their weakness is source of marginalisation.

Their contestation of the global order can only be verbal as they don’t have the means to conduct concrete actions to change it. They are heavily reliant on collective efforts.

Here “small countries” not only include island States in the Pacific Ocean with few thousands citizens but also countries like Qatar, Djibouti, Singapore and Bahrein. They have to become “cunning” and use their resources, location, laws and allegiances so as to stand out and thus survive in the international system.

VI. Functional Inequality: Being Excluded from Governance

A. Minilateralism

According to B.Badie, multilateralism has only been established for form while minilateralism is how decisions are actually made at the international level. Minilateralism consists of small informal circles or clubs where gather the most powerful countries like the UN Security Council or the G8.

This approach assumes that having too many countries involved in negotiations slows down the decision-making process and results in deadlock. Minilateralism carries the illusion that with less countries, more solutions will come up. For B.Badie, minilateralism not only causes humiliation for those excluded from the decision-making process (denial of equality) but also is source of inefficiency because local actors and those directly impacted by a given decision don’t have their say.

B.Badie analyses minilateralism as a preservation tool for the West to perpetuate its dominance rather than as an efficient and modern way to make decisions at the international level, as Western powers try to portray it.

B. Oligarchic Pressure

B.Badie here describes extra-institutional groups of countries that propose themselves for the resolution of a particular crisis. For example, in 1994, a group was formed by the US, France, the UK, Germany and Russia to attempt to solve the Yugoslav crisis.

The problem with these groups is that they often don’t include regional and local actors in their endeavour. Therefore, in a messianic approach, few countries confiscate the resolution of a given local crisis.

According to B.Badie, conflict resolutions have actually turned into credibility competitions in which the question of one’s status takes precedence over the nature of the crisis.

There needs to be a mix between multilateralism and regionalism, as Kofi Hanan suggested in 2012 in his role of mediator in Syria.

C. A Certain Diplomatic Paternalism

Putting an end to diplomatic relations is something rare nowadays but trying to marginalise another country is more and more frequent. This marginalisation can take various forms such as exclusions from negotiation groups, from international financial organisations and systems, from UN development programs, from sporting competitions…

It establishes a logic of punishment in which the one that punishes deems itself superior and legitimate to do so. For instance, in 2013, the US and France considered the possibility of sanctioning the Syrian regime for using chemical weapons on its population. They didn’t seek to overthrow the Syrian regime, which would have been a retaliation, they instead engage in a sort of administration of morality.

VII. The Mediating Role of Societies

A. The International Mobilisation of Societies

Humiliation that fuels populism and nationalism is not always felt in a top-down way. It can also come from grassroots levels and lead society to take action themselves and circumvent States’ inertia and usual caution in the international realm like in China during the 1899-1901 Boxer Rebellion. Therefore, non-State and non-organised groups emerge and become key actors of international relations that cannot be dealt with in an institutional way like with State actors.

Besides, new information and communication technologies allow populations to communicate with each other and easily see the Other in its alterity.

B. Neo-Nationalism and Fundamentalism

B.Badie analyses the case of Salafism whose religious fundamentalism can be regarded as a counter-attack against a humiliating modernisation imposed by the West. However, by refusing the ijtihad (innovation and adaptation to modernity), Salafism gets stuck with an impossible choice between modernising itself, which means westernising itself, and challenging the Western world order by reverting to a certain golden age.

In some instances, it’s not power that humiliates, it’s the inability to seize it that does. Indeed, Salafism is unable to either fully imitate dominant powers of the West or to defeat the Western order and replace it with a new model of society.

C. The Insoluble Contradictions of the Arab Spring

The Arab spring was a social and metapolitical movement without leader, party or ideological framework. As a matter of fact, it gathered people from various walks of life around a feeling of humiliation. However, this movement was torn between the desire for modernisation (imitation of the West) and the political use of traditions criticising the established global order (rejection of the West).

VIII. Are there Anti-System Diplomacies?

A. Oppositional Diplomacies

This type of diplomacy opposes the established international system including its actors, institutions, practices and legitimacy. Examples can be found with the Non-Aligned Movement, the G77, Cuba under Castro, Libya under Gadafi, Venezuela under Chavez, the OPEC… The anti-western rhetoric has become a federating factor for these actors that share a similar relative weakness and marginalisation on the international stage.

B.Badie describes it as participating in a competition not for power but for autonomy since the “game” is asymmetrical.

B. Diplomacies of Deviance

Practicing diplomacy of deviance implies displaying one’s difference and asserting oneself, sometimes by provoking established powers and transgressing their rules and values. However, countries that adopt this kind of diplomacy expose themselves to moral condemnation, marginalisation and sanctions, which can fuel even more their willingness to deviate from the established order.

A diplomacy of deviance brings a country in the spotlight way more than its actual resources would have.

IX. Uncontrolled Violence

A. New Conflicts, New Violence

Today’s conflicts are characterised by the increasing use of light weapons, the involvement of militias that replace national armies, and the influence of warlords that replace heads of State and government. Moreover, hatred for one’s opponent has almost nullified chances to negotiate and peacefully resolve conflicts. Additionally, proxy wars have become the norm, which fosters the idea that rich powers of the North manipulate and take advantage of conflicts happening in the South.

Humiliation also takes a greater role in the emergence of internal conflicts. In fact, poor and weak States often end up coping with a sub-military and intellectual elite that seeks more recognition. Furthermore, there is the humiliation created by political systems that favour certain communities over others.

B. Violence and Social Integration

According to B.Badie, violence is now decentralised, diffuse and fragmented. It takes on new forms that fail to be recognised in their diversity as they are all labelled as “terrorism” in which acts of resistance, hopelessness, demonstration and fanaticism cohabits.

These new forms of violence find their roots in failed national, political and social integrations. Many al-Qaeda leaders actually shared a same symptom: they failed to integrate into the Western world and globalisation.

A lack of national integration is the lack of recognition of one’s nation and constitutes the utmost humiliation that a people can receive. Examples can be found in the cases of Palestinians, Kurds, Sahrawis, Tuaregs, Uyghurs, Indian Muslims…

A lack of political integration refers to the absence of a structured political body which makes citizens’ participation in public affairs almost impossible. It is for example the case today in the Central African Republic and in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

A lack of social integration reflects a situation in which inequalities created by globalisation are not only more visible but also more deeply entrenched and harder to escape from.

Conclusion

B.Badie reminds that those who’ve been humiliated one day will most likely seek to become humiliators the next day. He also highlights the fact that small marginalised countries have a power of nuisance and that they can impact the global balance of power.

B.Badie recommends a new global approach to foreign policy. It has to be:

- A policy of alterity: considering the other as one’s equal and avoiding alienating it in order to create functional partnerships;

- A social policy: favouring the integration of all populations in decision-making and moving away from past political and military agendas;

- A multilateral policy: pursuing the common interest and not the one of any superpower.

0 Comments